I recently let my guard down and got nostalgic. I let my attention shift momentarily away from the all-consuming stream of horrifying hard news that defines all of our lives all of the time or else, and leafed through the books I used to love in high school. In my case, that means humor books for baby boomers, which I used to read cover-to-cover while standing in B. Dalton, the tiny chain bookshop in my local mall.

But all that reading just made things worse.

I used to like books by Al Franken, Dennis Miller, and Bill Maher, but this time around I needed to stay away from such overtly political thinkers. To that end, my first mistake was thinking it would be worth a few laughs to revisit a book of old Andy Rooney rants. I remember Andy as an elderly crank who was mad on TV about the price of stamps, but the political content of Years of Minutes: The Best of Rooney from 60 Minutes had been curated in such a way that it presented a fairly complete portrait of Rooney’s political beliefs — basically, that we should all trust the president more, the government is pretty darned great, and that when America does war crimes, it’s in the service of a kind of well-intentioned international project we’re working on, so quit burning our flag you ungrateful ding-dongs! Also, he didn’t like to use apostrophes for some reason.

At one point, he actually says of Vietnam, “We didnt [sic] do it for any selfish, evil reason. There was nothing in it for us, economically." It was an unwelcome reminder that Teenage Me bought into Andy’s ideas hook, line, and sinker until sometime between the invasion of Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq, and that the best thing you can say about the Trump presidency is that he’s largely exposed Andy’s pleasant framing of US politics as at best a delusion, and at worst, a lie. Needless to say, I had to slide that “humor” book back onto the shelf and find something more side-splitting.

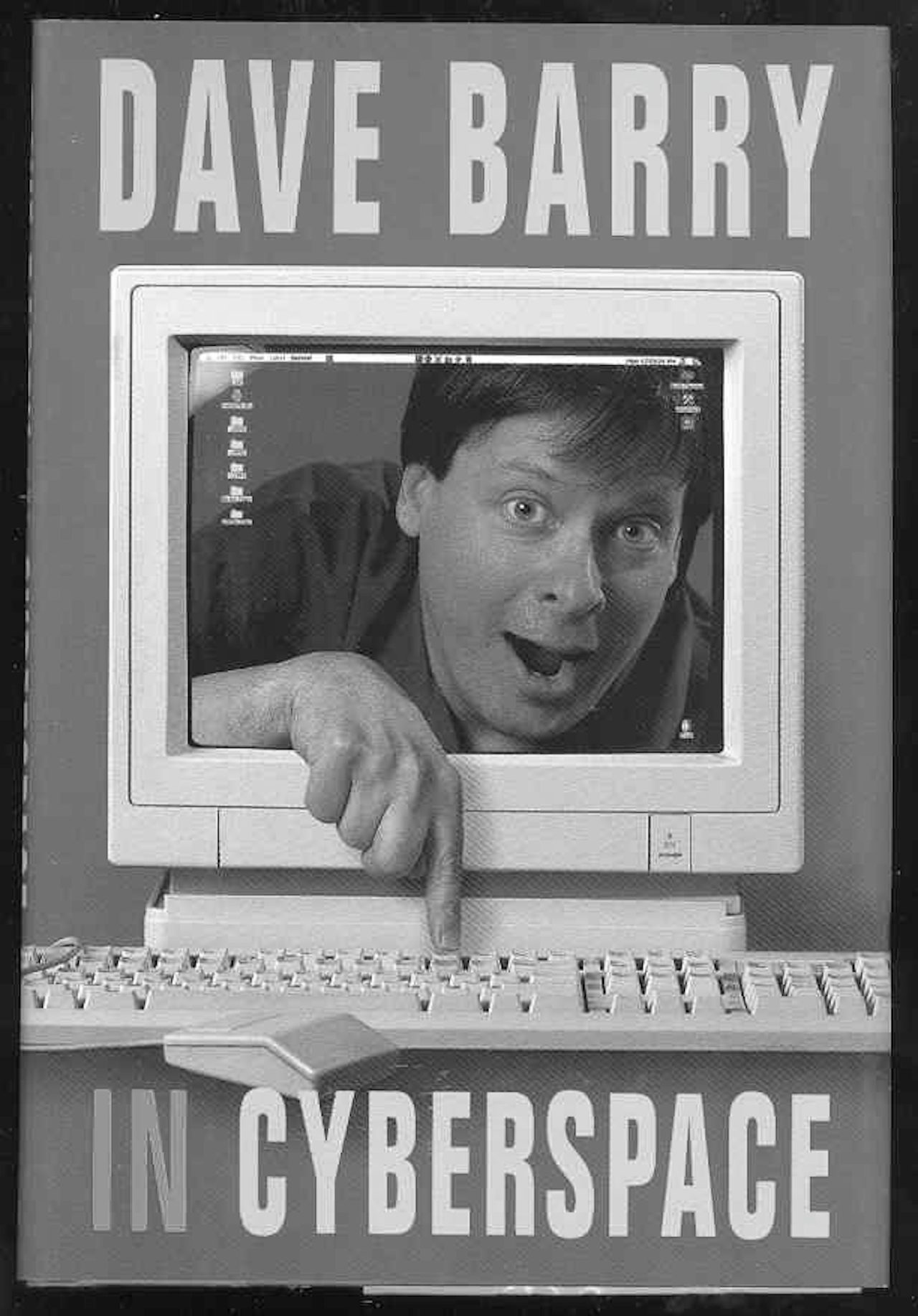

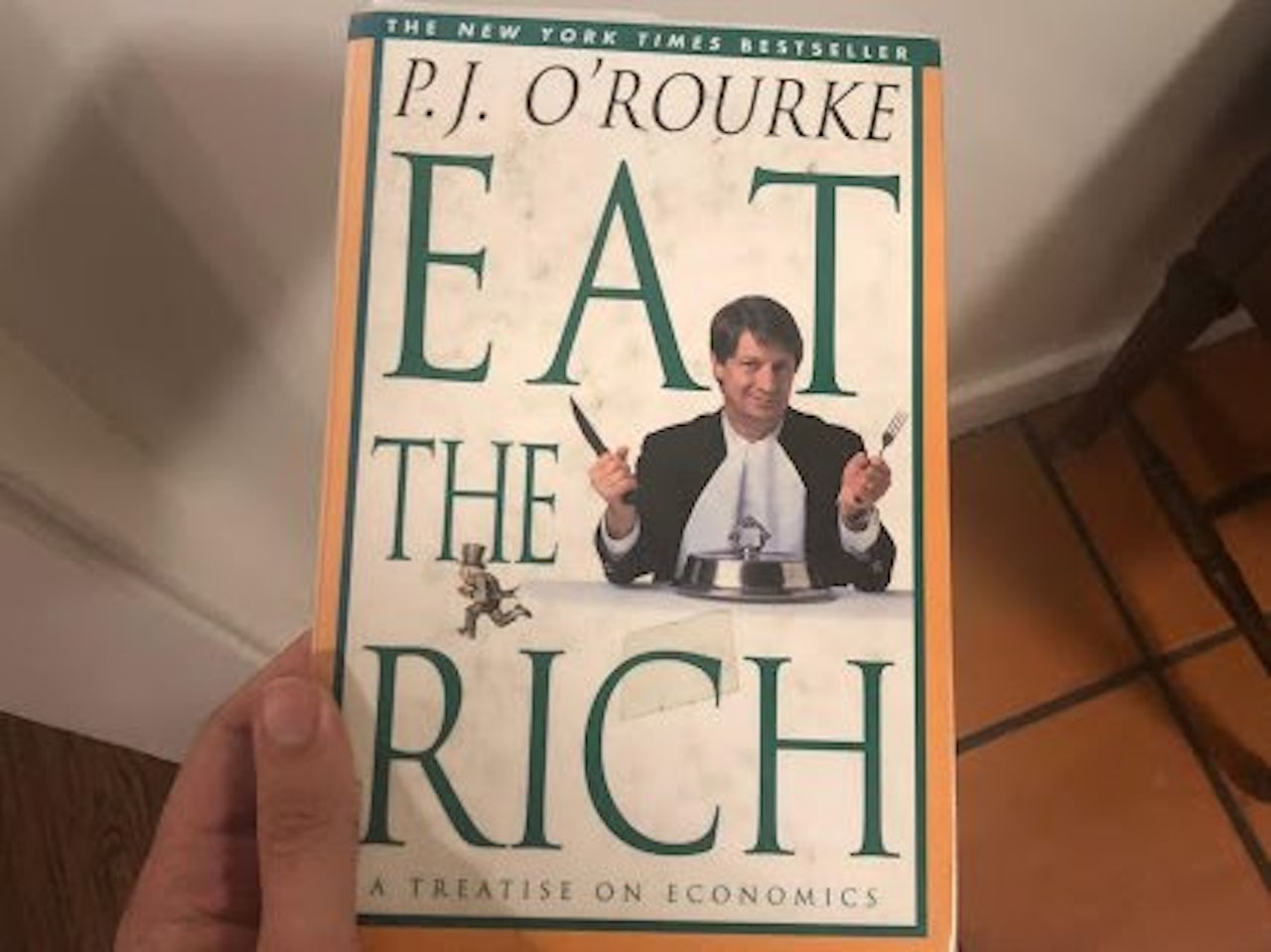

Today, humor books are mostly book versions of funny social media accounts — like Alexandra Tweten’s Bye Fellipe or the Shit My Dad Says book — but in the 90s and early 2000s, the “humorists” I read were mostly opinionated media personalities. In heavy rotation for me were Dave Barry, the legendary syndicated columnist with a penchant for surrealism and a deep distrust of any government institution; Erma Bombeck, who I didn’t realize was already dead by the time I was reading her observations about hotels and airplanes; and Al Roker, who, it seems, wanted to be an observational comedian briefly in early 2000s. I also count slightly more literary figures who I used to read back then — like P.J. O’Rourke (who got his start at National Lampoon) and Bill Bryson — as humorists.

But the problem with my whole trip down memory lane was that much of what humorists were doing in those days was complaining about the kinds of things people are still very worried about today: a near-total distrust in institutional norms, class warfare, US imperialism, intergenerational warfare, and despair over climate change. Every white-knuckle, life-or-death, high-stakes current event shows up again and again in these books, except when it does, the author then says something to the effect of “they’ve gotta be kidding me!” and at the time it was all a barrel of laughs to read. I remember that being the case, even if — tragically — there’s not enough nostalgia power in the world to get me back into that headspace.

In short, I was reading brightly-colored, 20-year-old books with smirking boomers on the covers, but the topics they covered were relevant, which means it’s like you’re going back and watching the beginning of a movie with an unexpectedly tragic twist ending. For all the “humor” I got out of the experience, I may as well have been back on Twitter, reading about people getting fired from the Trump White House.

I threw P.J. O’Rourke’s Eat the Rich across the room pretty shortly after I picked it back up. I had gravitated toward it in my B. Dalton days because of its tantalizing title, and I was thrilled to find a “Treatise on Economics” with boob jokes in it — a quick shortcut to teenage me maybe knowing something about economics, as opposed to nothing. But O’Rourke’s sojourn around the world in search of an answer to the question, “Why do some places prosper and thrive, while others just suck?” leads him to the simplistic conclusion that, “Almost everyone in the world now admits that the free market tells us the economic truth. Economic liberty makes wealth. Economic repression makes poverty.” Today, O’Rourke is a research fellow at the Cato Institute, the libertarian think tank co-founded and largely funded by Charles Koch, and in the 20 years since he sarcastically titled his book Eat the Rich, the prospect of actually eating them has only gotten more popular.

I’m not saying all the humor was overtly political back then. Yes, there was a lot of Lewinsky stuff, but mainly every Y2K-era humorist was influenced by Seinfeld, so in their books they seem weirdly mystified by everyday life, especially hotels and motels — a theme that shows up again, and again, and again. In fact, almost every page in every 1990s humor book has some variation on “I can’t believe they invented this crazy thing!” and that was what I wanted back then. When I first read these books when I was 15 or so, it felt to me like every new mall was a gift from the capitalism gods, and the occasional absurdity was just a funny glitch in an otherwise perfect system. Great hilarity, therefore, could be derived from goofing on stores, products, and commercials, or if a humorist was pressed for time, just saying the names of products — the ”McDLT,” for instance, or “Crystal Pepsi.”

“I am a GapKids addict” Al Roker writes in Don’t Make Me Stop This Car, his humor-memoir about 90s fatherhood, published in 2000. “I don’t know about your town, but here in Manhattan there are more GapKids than Starbucks. If The Gap and Starbucks ever decided to take over the world, we’d all be caffeine-drinkin’, khaki-wearing’ zombies.”

Al’s Gap jokes sound like a million other Gap jokes from around that time, which is, in and of itself, a little disturbing in retrospect, because they were published around the time we found out about Gap, Inc. sweatshop workers in Saipan being forced to get abortions, and because 20 years later, The Gap’s policies towards ethically fraught sourcing haven’t noticeably changed. But it also disturbs me that Al’s prose style seems to have been the basis for Mike Huckabee’s Twitter voice.

Will be on @seanhannity 2nite @FoxNews at 9pmET but not to talk, but to deliver pizza to his guests. I'm thinking pepperoni. I'm adding extra cheese for them. I hope they tip well! pic.twitter.com/u3sYkkU5vC

— Gov. Mike Huckabee (@GovMikeHuckabee) November 26, 2018

More queasily relevant than Roker’s khaki observations is the 29th chapter from Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner’s 1997 book, The 2000 Year Old Man in the Year 2000. It’s about global warming, and today, it’s about as funny, as, well, global warming:

Like other people, I worry constantly about the so-called greenhouse effect. Every year the world’s temperature increases in small increments. In my own lifetime, I’ve seen it go from mild to warm to hot. A lot of people are trying to do something about it. Saving our environment is one of the wonderful causes I believe in. Last year I gave twelve dollars anonymously to my favorite charity, Out Goes the Bad Air, In Comes the Good Air, Inc. That’s how concerned I am.

My great fear is that the temperature will continue to rise. If it does, it will be a disaster. I’ll have absolutely no use for my entire winter wardrobe.

In the 2000 book In Our Humble Opinion: Car Talk's Click and Clack Rant and Rave by Tom and Ray Magliozzi of NPR’s Car Talk fame, the MIT-educated Click and Clack question the wisdom of deregulating the airline industry — which was nearly reversed this past August — and rail against bottled water — which looks like it may be next after that whole straw thing. But the book also contains a downright intense rebuke of the MSM:

As I was channel surfing one night, I ran across one of those pseudo news programs where ‘responsible’ journalists sit around and discuss what they’re doing. I tuned in too late to know who any of these schlocks were, but one of them was from Time or Newsweek, I forget which. Here’s how he justified his magazine’s coverage of this Monica [Lewisnky] story: ‘This is what people are talking about, so it’s our responsibility to write about it,’ he says.

You jerk! Don’t you have it bass ackwards? Aren’t people talking about it because you’re writing about it? How would we even know about it if YOU hadn’t decided that it was news? It’s not news, stupid. And just because you’ve got a bigger vocabulary than I, it obviously doesn’t qualify you to decide what’s ‘fit to print.’

Here’s Dave Barry in 1997’s Dave Barry is from Mars and Venus, subtly shedding light on how it’s the president’s job to lick the boots of dictators in order to score trade deals:

[M]ost of us had no idea what U.S. foreign policy was until the election of Bill Clinton, who, to his credit, has established a clear and consistent foreign policy, which is as follows: Whenever the president of the United States gets anywhere near any foreign head of state, living or dead, he gives that leader a big old hug. This has proven to be an effective way to get foreign leaders to do what we want: Many heads of state are willing to sign any random document that President Clinton thrusts in front of them, without reading it, just so he will stop embracing them.

There’s only one piece of light reading that I rediscovered in my plunge down the nostalgia hole that I can actually recommend unreservedly to pretty much anyone: Bill Bryson’s 2000 book I'm a Stranger Here Myself: Notes on Returning to America After 20 Years Away, a collection of newspaper columns from 1996-1998. Bryson is an American-born British citizen who dabbles in serious history and science, but I picked up Stranger as a teen because I wanted to read a collection of goofs about how LOL, us Americans have too many cupholders in our cars. It is that — Bryson devotes the space of an entire column to something called a “breakfast pizza” that he found in the freezer section of his local supermarket, but the book also includes razor-sharp observations about some of America’s foibles that — whoops! — turned out to be intractable problems that are tearing at the fabric of our society with tragic results.

Here’s Bryson on GDP’s inadequacy as a measure of economic prosperity, particularly as it relates to the environment — which, as you may know, is an issue of immediate and pressing concern: “GDP is a perfectly useless measurement. All that it is, literally, is a crude measure of national income — ‘the dollar value of finished goods and services,’ as the textbook puts it — over a given period.” Later Bryson notes that, “bad activities often generate more GDP than good activities,” and sums up by saying, “In short, the more recklessly we use up natural resources, the more the GDP grows.” Here in 2018, we have 12 years to transform the whole global economy, and fear of declining GDP is arguably the biggest obstacle in the way of that transformation.

In an article on the absurdity of drug tests, Bryson points out that convicted drug offenders in some states couldn’t collect welfare. They still can’t in some states. He notes in another chapter that Americans are blasé about guns, but, “Show most Americans an egg yolk and they will recoil in terror.” At the end of a funny anecdote about a problem with his British wife’s immigrant status, he notes, “I have learned from years of experience that there is not the tiniest chance that a U.S. government employee will bend a rule.” And of course, two decades later, US government employees (and contractors) took this inflexibility to new heights by upholding a rule that put children in cages earlier this year.

But I’m not saying America’s humorists in this era were all hyper-perceptive Mark Twains whose sharp wit and satirical eye cut through the noise and held the powerful to account. Far from it. I think they were mostly making facile jokes for a broad audience, but pick your cliché about how “comedy reveals underlying truths.” The topics the people were joking about back then are all anyone ever talks about anymore, except none of it is funny — in fact, this stuff was probably never funny. It was urgent then, and it’s even more urgent now.

Meanwhile, the main joke everybody makes all the time now is that one about wanting to die. It’s not any funnier than an Al Roker book, but there’s probably some sort of important lesson in there somewhere if we look hard enough for it.