DEC—11—2018

Long before Elon Musk, a visionary automaker showed how ugly the American Dream could be.

Produced in partnership with Epic Magazine

PART ONE

The Crash at Lime Rock

In Zachary DeLorean’s little house on Detroit’s Near East side they speak Rumanian. Zachary is from Bucharest. Zachary has a way with machines but his poor English holds him back. He starts and ends his career on the factory floor at Ford. He’s a thwarted man and a payday drunk. He fights in bars and knocks his wife around. Her name is Kathryn Pribak DeLorean. Their oldest son is John DeLorean, born January 6, 1925.

She divorces Zachary in the ‘40s and John never sees him again. When Zachary dies of throat cancer in 1968, the Ford plant calls and asks John to come pick up his father’s toolbox. John lives with his mother until he marries Elizabeth Higgins in 1954. She’s a phone-company receptionist. They never have children.

In 1956, John DeLorean leaves a research and development job at Packard and goes to work for General Motors. At the time it’s the biggest car company on Earth. DeLorean works in engineering at Pontiac. It’s a struggling division with no real brand identity, but John’s new boss, Bunkie Knudsen, is beginning to turn things around. He’s started supplying Pontiac product to stock-car drivers. NASCAR is a decade old and Cotton Owens has just won a title at the Daytona Beach & Road Course in a Pontiac.

Bunkie’s betting that an association with speed and excitement will help move Pontiacs. Implicitly he’s betting on youth. You can’t sell an old man’s car to a young man, Bunkie likes to say, but you can always sell a young man’s car to an old man.

The rest of the industry doesn’t think this way. Bunkie’s superiors aren’t thinking about speed or youth or action. Each day the auto-industry princes of General Motors leave their homes in Birmingham and Bloomfield Hills and drive to work — down Woodward Avenue, which runs shotgun-straight from the Detroit suburbs to GM headquarters — in big General Motors cars built to ride as smoothly as sailboats on glassy water. From where they sit, it’s hard to imagine anyone wanting something different from a car. Former Car & Driver editor Brock Yates will later call this strain of confirmation bias the “Detroit Mind.”

In 1961 Knudsen is appointed general manager of Chevrolet. His chief engineer Elliott “Pete” Estes succeeds him at Pontiac, and John DeLorean takes over for Estes. He’s 36.

After work the Pontiac engineers test-drive prototypes that will never see the floor of a dealership. When the streetlights come on Woodward Avenue becomes one of America’s hottest drag strips. Sometimes kids pull up at stoplights next to shirt-sleeved GM engineers driving cars with code names. Sometimes the GM guys blow the kids off the road.

In 1963, John and his team start to wonder what would happen if you threw a 389-cubic-inch V8 engine fit to power a full-size Bonneville into a smaller car, like the midsize Pontiac Tempest. What happens is you create a maneuverable but brawny car with a race-friendly surplus of power and torque.

There’s a companywide rule capping engine displacement in midsize cars at 330 cubic inches. It exists in part to prevent GM engineers from making a hopped-up car like this one available over the counter. With Estes’ approval, the team smuggles the 389 past GM’s Engineering Policy Committee by hiding it in a $296 option package on the ’64 Tempest. John, a sports-car aficionado, borrows an acronym from a line of limited-edition Ferraris — Gran Turismo Omologato — and christens the option the “GTO package.”

Dealer orders start pouring in and they’ve sold 5,000 before GM figures out what’s happening. John and his team have just put General Motors in the muscle-car business.

Years later, in his book The Decline and Fall of the American Auto Industry, Brock Yates will write that powered-up midsize cars like the GTO “represented a missing link between the ostentatious landmarks Detroit was building and the smaller, more maneuverable, technically sophisticated imported sports and economy automobiles that were beginning to arrive on our shores in the mid-1960s.”

He’s the only person at General Motors with a Snoopy poster hanging in his office.

“Had they looked beyond their hood ornaments,” Yates continues, “the Bloomfield Hills contingent might have recognized that the so-called teenage punk street racers and their bouffant-haired girl friends could tell them more about the shifting tastes in cars than all the stultified market research being produced to satisfy the preconceptions of the Detroit Mind.”

It’s this second part— about young punks and teenyboppers knowing everything— that John takes to heart.

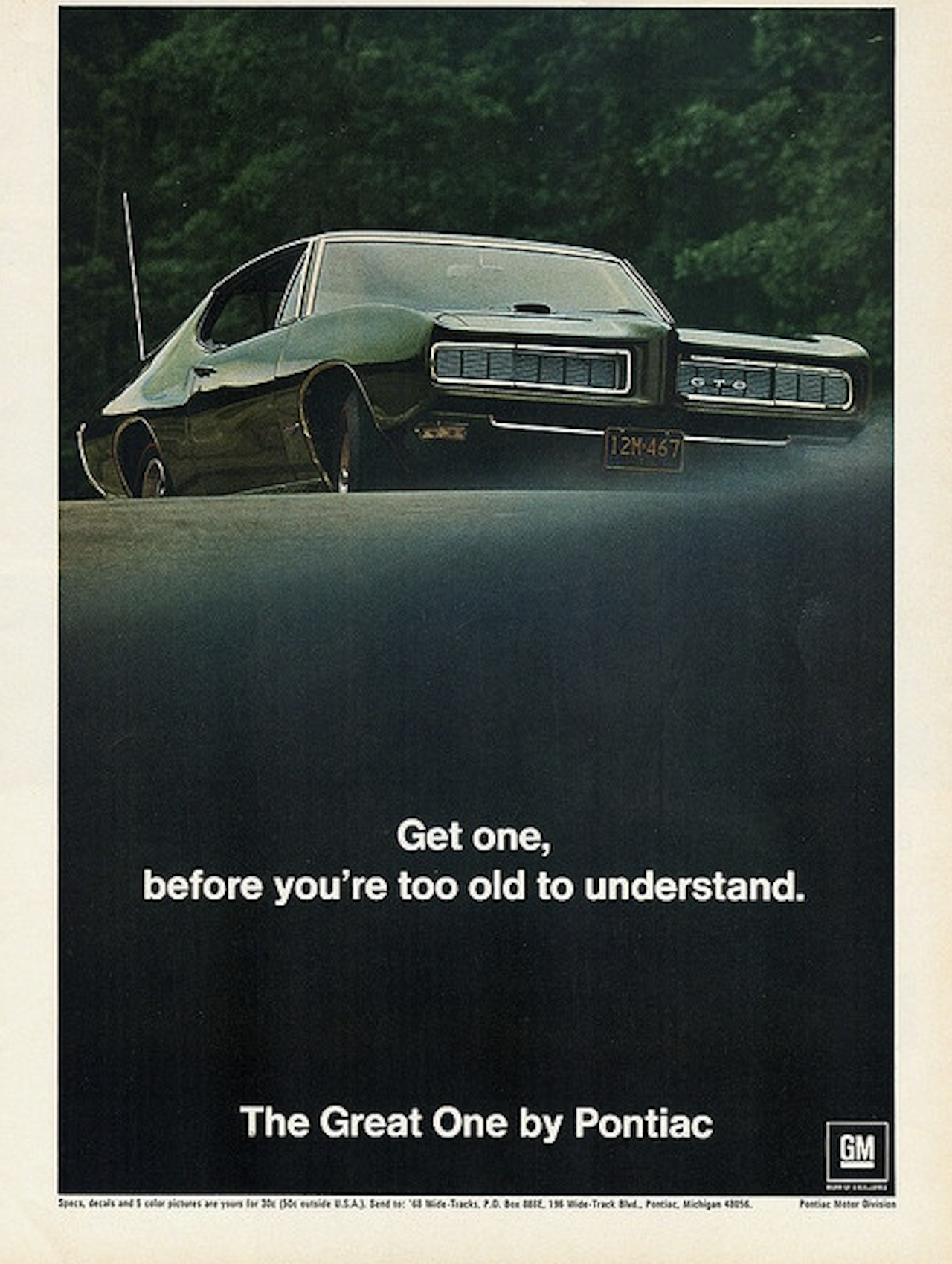

He understands firsthand the factors that might spur an old man to buy a young man’s car, and exploits them. (Get one, a 1968 GTO print ad urged potential buyers, before you’re too old to understand.) But that’s not enough. The magazines frame him as a go-go exec dialled in on youth culture; he begins to remake himself to suit that image. He quits smoking. He drops a bunch of weight. He grows out his sideburns and starts dyeing his hair jet black. He starts showing up to manage a division of the most conservative corporation in America dressed like he manages the Partridge Family — turtlenecks, jewelry, tennis shoes or Chelsea boots. On weekends he steps out in shirts unbuttoned to the sternum.

He’s the only person at General Motors with a Snoopy poster hanging in his office. He’s a survivor of the Great Depression who served in the Army during World War II, but suddenly he’s the rebellious teenage son living under GM’s roof. Although the term has yet to enter the pop-psychological lexicon, he may be having a midlife crisis and calling it market research.

Eventually he gets a facelift and an implant that reshapes his jawline. Later, he’ll tell Fortune he underwent reconstructive surgery after going through the windshield of a race-car prototype at the Lime Rock test track in Connecticut. He’ll say he recuperated in secret, because GM forbids such adventures by its top execs. When Fortune checks with the man who owned the Lime Rock track at the time, he will recall neither the accident in question nor any other instance of DeLorean driving a car there.

In 1965, he’s promoted to head of Pontiac. He’s the youngest man ever to head a division of GM. Reporters visit him at home and his lifestyle wows them. He lays it on thick and they take notes, breathlessly documenting his way-out taste.

John drives to work blasting the Jefferson Airplane. John name-drops Montaigne and Blood Sweat & Tears. John shows off his art collection and his drum-tight abs. John tells one reporter he’s writing a novel about nuclear war. John talks about young people leading a “neoreligious metamorphosis” in the culture and wonders aloud why his fellow auto execs feel obligated to vote Republican. John talks about studying the “underground papers” and FM rock radio for intel on the Love Generation as it comes of car-buying age. The line he keeps using is, “It’s the cheapest education you can get.”

The reporters file stories holding up DeLorean as proof that individualism and conviction aren’t irreconcilable with advancement inside the capitalist system. These stories arguably reveal less about DeLorean than they do about the professional anxieties of the people writing them. These are reporters whose beat has yet to produce a Jobs, Branson, Cuban, Zuckerberg, or Musk, but when they write about John DeLorean, they’re workshopping now-familiar strains of magical thinking. The story of the rest of DeLorean’s life will be a cautionary tale about mistaking swaggering entrepreneurs for rock stars, prophets, or kings.

The Detroit papers aren’t nearly as impressed. The Free Press runs a blind gossip item about an auto executive getting surgery “to look like the Pepsi generation.” So of course California beckons. Cradle of car culture, wellspring of youth fads, a place where no one cares what your old Detroit face looked like.

The state’s already huge in DeLorean’s psychogeography. DeLorean’s mother Kathryn had family on the West Coast. She’d take John and his siblings to live out there for months at a time when things got rough at home.

John and Elizabeth split up in 1968. She sues for cruelty. She keeps the house. Later she shows reporters the bills from a Swiss plastic surgeon that keep coming in the mail. By then John is going to California as often as he can.

“John would descend the steps from the GM corporate plane with his sunglasses on and his coat over one arm,” wrote former Popular Mechanics editor Jim Dunne in 2005. “‘Ready to party’ is an accurate description.”

John takes out Joey Heatherton. John takes out Ursula Andress. John takes out Candace Bergen. John takes out Nancy Sinatra.

John makes the scene at the Daisy, Jax sportswear kingpin Jack Hanson’s members-only nightclub on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, where on any given night you might see Mia Farrow, Dickie Smothers, Oleg Cassini, or Ryan O’Neal.

Some weeks John flies out to the coast on Thursday and comes back to Detroit on Tuesday, just long enough to check the mail and toss some junior exec a tube of pink lipstick, telling them Nancy Sinatra needs a Firebird that color and Nancy with the laughing face needs it in four days.

John gets another big bump in 1969, taking over as head of Chevrolet when Pete Estes gets promoted. In California he pals around with Sammy Davis Jr. and Johnny Carson. He rolls with playboy entrepreneurs, race-car drivers, TV producers — guys who’ve made their first millions and slipped the corporate yoke.

Their whole conception of money is different. John can throw GM’s money around but at the end of the day it’s still GM’s money. It might as well be currency with the owl eye of GM’s old chairman Alfred P. Sloan on the back for how narrow a steak-and-chops lifestyle it buys you in Bloomfield Hills.

John starts to look around for other income streams, new ways to leverage being the chairman of Chevrolet. He buys a little piece of the San Diego Chargers. He sits on a few startup-company boards. This gets back to GM and rankles the brass. Only one company is supposed to matter to a man from General Motors.

The merry-go-round stops for single John in 1969. He marries a California girl — Kelly Harmon, of the Brentwood Harmons. Her father is Tom Harmon, the college-football legend, star of his own biopic, war hero and sportscaster. Kelly is 20. DeLorean is 44. They’re married at the Bel Air Country Club in May. Some of Hollywood’s biggest names — like the actor and singer Ricky Nelson, then married to Kelly’s sister Kris — mingle at cocktail hour with some of Detroit’s. There are guards outside in radio cars and guards inside watching on closed-circuit TV. The Robert Mitchell Boys’ Choir sings a song about Kelly written by DeLorean.

In a report on the wedding, The New York Times describes DeLorean as “a seven-handicap golfer and tennis enthusiast, who wears sideburns and big moon sunglasses, and shocks his conservative colleagues by frequently driving a $19,000 Maserati Ghibli instead of some G.M. product.” In Harmon, The Times suggests, DeLorean “may have taken a wife who can match his zest for life.”

“I like riding, skiing, water skiing, music, swimming, poetry, parties, and dogs,” Kelly Harmon tells the paper of record.

They adopt a son and name him Zachary. They share a distaste for Detroit social life and tell reporters they’d take a moonlit horseback ride over a Bloomfield Hills cocktail party any day of the week. For a while having this in common is enough. But before long Kelly’s spending more and more time back in California without him. They separate in 1972. A magazine photographer visits DeLorean at home not long afterward and captures the swinger wandering his property in Bloomfield Hills in nothing but blue jeans, lonely as Jonathan Livingston Seagull.

Kelly tries to take Zachary to live with her parents. John hires private eyes to signal his readiness for war. Their divorce is settled out of court in 1973. John gets custody of the kid. “To this day,” he writes in his autobiography, “I can’t remember one meaningful conversation we had. I should probably have simply had an enjoyable affair with her and then moved on to more mature relationships.”

Later, John tells a friend that after the separation, his Hollywood friends treated him to a weekend in Malibu with three prostitutes whose California-girl looks resembled Kelly’s.

“He said it was the classiest thing anyone had ever done for him — that was his phrase, classy,” an associate says. “And he said it could only have happened out there in California, that no one in Detroit would have enough class to pull off something like that.”

The first time John DeLorean sees Cristina Ferrare it’s 1972 and he’s on an airplane, skimming Vogue. Captivated, he tears a five-page spread out of the magazine and saves it in his briefcase. Cristina is a butcher’s daughter from Cleveland by way of Los Angeles. She’s been a model since her teens and is starting to act. She’s just played Cliff Robertson’s hippie love interest in the 1971 rodeo-circuit drama J.W. Coop. “I felt a bit sheepish,” DeLorean writes in his book, “like a teenager with a crush on a movie star.” She’s 22 — two years younger than Kelly Harmon. He’s 48.

A few months later, DeLorean meets some friends for cocktails at the Bel Air Country Club. DeLorean’s friend Roger Penske announces he’s taking Cristina Ferrare out. DeLorean’s divorce lawyer, E. Gregory Hookstratten, sees DeLorean perk up at the mention of Ferrare’s name. Hookstratten is also Ferrare’s divorce lawyer. Hookstratten, evidently some kind of romantic, takes DeLorean aside and offers to broker an introduction.

He actually meets her in September 1972 at a Gucci show she’s walking in. At the time, she’s casually seeing an acquaintance of DeLorean’s, Fletcher Jones, who sells data-processing software and breeds horses. He dies in November when his Beechcraft airplane crashes into a hillside near Santa Ynez airport. Once he’s been dead for an appropriate length of time — but before the end of 1972 — DeLorean calls Cristina and takes her to lunch at the Daisy. He has plans to spend the holidays skiing in Vail with a different woman, but breaks them to be with Ferrare. “I had no qualms about it,” he’ll write later. “I wanted Cristina for Christmas.”

At some point while he’s at Chevy, GM reportedly investigates DeLorean for taking kickbacks from parts suppliers. Word of the investigation leaks to an industry newsletter but GM takes no official action. He gets promoted again in 1972. He’s now group executive in charge of GM’s North American car and truck division. His new office is on the 14th floor of GM headquarters, behind an electronically locked door, in the oak-paneled cloisters of America’s corporate Vatican.

In On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors, an axe-grinding 1979 tell-all he dictated and then tried to disavow, DeLorean writes that the door is locked “because there is a very great fear on The Fourteenth Floor that someone will burst into Executive Row and do them ‘great bodily harm’— a radical leftist, an irate customer, a furloughed blue-collar worker.”

Running a division of GM back then was like ruling a nation-state on behalf of a larger empire. 14th-floor executives at the center of GM’s wheel-and-spoke corporate structure enjoy far less autonomy. Pushing paper and courting favor is no way for an automotive swinger to live. John experiences an existential crisis — or so he tells journalist Gail Sheehy in Passages, her 1976 collection of midlife-crisis case studies, in which DeLorean, a brave and proud midlife-crisis survivor, is the only public figure who chooses to forego a pseudonym.

“Here I was spending my life bending the fenders a little differently to try to convince the public they were getting a new and dramatically different product,” he says. “What gross excesses! It was ridiculous. I thought, there’s got to be more to life than this. Am I doing the thing God would have me do here on earth?”

There’s also the fact that DeLorean’s peers on the 14th floor don’t like him. All that cocktail-party politicking he’s avoided has cost him. Flouting the dress code and blowing hard in interviews has cost him. He’s come this far without making a lot of friends.

One of his bosses warns him to “disappear into the wallpaper” now that he’s a 14th-floor executive. Asking him to stay out of the papers is like asking him to stop breathing.

In the fall of 1972, DeLorean’s asked to address a triennial GM conference so private they hold it at the Greenbrier, a remote luxury hotel in West Virginia, the amenities of which include a massive underground bomb shelter built to house emergency sessions of Congress in the event of a nuclear attack on Washington. They tell John to write a gloves-off speech about quality control — the effect of warranty repairs and recalls on the company’s bottom line, that sort of thing. He does.

The men from General Motors gather in the Greenbrier’s Exhibit Hall, the entrances of which are fitted with concealed blast doors weighing up to 28 tons, so that the whole room can be sealed off at a moment’s notice from a burning world. Although it’s never used to ensure the safety of Congress before it’s decommissioned in 1992, it serves its purpose in other ways. In a sense this meeting of the men from General Motors is a joint session of Congress, and in the Exhibit Hall they’re safe from everything except maybe the symbolism of holding your secret meeting about the future inside a bomb shelter.

Days before the summit, the text of John’s speech leaks to a columnist at the Detroit News. The story gets picked up nationally and the headline “GM Warns its Executives to Improve Auto Quality” appears in The New York Times.

DeLorean huffs that he’s been sandbagged. GM hires a private investigator named C.J. Pickerell to look into the leak — and into DeLorean. Eventually Pickerell delivers to GM what former DeLorean Motor Company vice president William Haddad will later describe as a 19-page dossier containing “certain allegations about John’s personal life,” as well as evidence suggesting that the person responsible for the leak of the Greenbrier speech may have been DeLorean himself.

General Motors announces John’s resignation in April 1973 and has never offered further comment on the end of his tenure at the company. They treat it like he’s retiring. They pay out his bonuses. They install him as head of an auto-industry backed nonprofit, the National Alliance of Businessmen, and give him the keys to a Cadillac dealership in Lighthouse Point, Florida, right between Boca Raton and Pompano Beach. Three weeks later he marries Cristina Ferrare at a friend’s home in Los Angeles.

Because it’s in GM’s best interest to say nothing, John walks away from the company with full control of the narrative. He’s now the man who fired General Motors. He hits the lecture circuit, writes an op-ed or two, leans into the role of car-business apostate, scores points off his old colleagues and their stubborn refusal to forsake “the grotesque monsters of the 1960s and 1970s.” The first OPEC embargo has just driven gas prices through the roof. The number of Americans to whom big-car ownership suddenly seems obscenely wasteful is growing by the day. It’s a good time to be out there saying things like these.

On the record he denies he’s going to start a car company, right up until he starts one. GM yanks his bonus the minute he publicly confirms the rumors.

He isn’t immediately laughed out of public life when he says it, which says something about how much people want to believe in John DeLorean. At the time, no independent automaker has challenged GM and survived since Walter Chrysler in the 1920s. Just two years before DeLorean announces that he means to build a very safe high-performance car, a fast-talking ex-Subaru importer named Malcolm Bricklin is in the process of launching a very safe high-performance car which he names after himself. Bricklin’s company goes into receivership in 1975. The Bricklin SV-1 will be remembered for two things: The speed at which its creator burned through $21 million in operating capital supplied by the province of New Brunswick, and its distinctive gull-wing doors.

A McKinsey study calculates DeLorean’s chances of success at one in 10. A Wall Street analyst will say later that when clients asked him about investing with DeLorean, he advised them “to put the money into wine, women, and song. I figured they’d get the same return and have more fun.”

No bank will stake him, so DeLorean goes looking for government development funds to build a factory. In February 1978, Businessweek reports that the company has been “flirting with Canada, Spain, Pennsylvania, Ohio and most recently his home town, Detroit.” Alabama Gov. George Wallace supposedly calls him more than once in the middle of the night to beg him to come build cars there.

Most of this is hype. But in 1978 DeLorean signs a preliminary agreement with the U.S. Department of Commerce and the government of Puerto Rico to build a factory on a former Air Force base in Aguadilla. Puerto Rico is still basking in the good news when John announces in August of 1978 that he’s gotten a better offer from the British government, and will build his factory in Northern Ireland, on 72 acres of muddy cow pasture in Dunmurry, County Antrim, just outside Belfast. The site is the no-man’s-land separating two housing estates — Twinbrook, populated mostly by Catholics driven out of central Belfast by sectarian violence, and Seymour Hill, which is largely Protestant.

DeLorean’s benefactors are Roy Mason, the Labour politician and British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, and the National Irish Development Agency, or NIDA. They’re hoping DeLorean can create enough jobs to stem the tide of blood in Belfast, where chronic unemployment has kept Irish Republican Army recruitment robust. DeLorean, with characteristic modesty, tells an associate, “I’m starting to think that God stuck me here to be part of the solution to the crisis in Northern Ireland.”

By the time DeLorean makes his deal with the British, IRA folk hero Bobby Sands has been convicted of firearms possession and incarcerated in Her Majesty’s Prison Maze, the detention facility known colloquially as Long Kesh or the Maze. The Maze is just down the road from Dunmurry. Bobby Sands’ mother still lives in Twinbrook.

In spring 1978, IRA prisoners in the Maze’s H-Block unit begin smearing their cell walls with excrement and refusing to bathe or wear prison uniforms. The so-called “dirty protest” is a step on the road to the hunger strikes that begin in 1980. By the summer of 1981, ten Maze prisoners — including Bobby Sands — will have starved themselves to death.

On October 2, 1978, John DeLorean comes to Dunmurry to break ground. With Don Concannon, the Labour Party’s Minister of State for Northern Ireland, he digs some holes and plants some symbolic trees. A chain-link fence holds back a group of protesters, mostly women and children. The protesters chant Brits out and Yankee go home and Smash H-block and sing the Irish national anthem.

Construction begins within weeks, delayed only by a disagreement over the fate of a lone hawthorn in the middle of the pasture. The Irish workmen are convinced it’s a “faerie tree” and won’t touch it.

“It was just a scraggly bush,” William Haddad writes, “but to the trained eye it had mystical qualities. According to the legend, if a person cut down a faerie tree, he would soon lose a limb in retaliation… Bulldozers skirted it, trucks avoided it.”

Then one morning the workmen show up and the tree’s gone. Someone has pulled it down overnight.

“It’s a bad sign,” Haddad quotes a dismayed Irish workman as saying. “It’s a dark day. You have wrecked everything we’re building. The faerie tree will see to that.”

PART TWO

Jar of Blood

“Car biz is hell...”

In the fall of 1982, Stephen Arrington’s boss, Morgan Hetrick, says he’ll give Arrington $20,000 to drive a car from Florida to Los Angeles. This isn’t the first time Morgan’s made him this kind of offer, in which he isn’t really asking.

Arrington is a four-tour Vietnam vet and a trained Navy diver. In 1972 he’s assigned to the naval air station at Point Mugu, in Ventura County, California. He swims after lost bombs and teaches scuba diving on the side. Hetrick, a pilot who owns an aviation company, pays him for lessons. They become friends, despite their two-decade age difference. Steve introduces Morgan to younger women. Morgan takes everybody out on his yacht.

They part ways by 1975. In 1979 Arrington is court-martialed for selling a small amount of marijuana to a fellow sailor; he winds up dishonorably discharged and working his way through San Diego State with a job folding T-shirts in a La Jolla surf shop.

Which is when Hetrick gets back in touch and asks Arrington to come work for him. Hetrick keeps planes in a hangar in the Mojave Desert. Arrington thinks learning to fly might beat folding T-shirts.

Hetrick owns patents. Hetrick was aviation magnate Bill Lear’s personal pilot for a while. Hetrick has wild stories about transporting planeloads of animals — various wildlife for nature shows, monkeys for science. He’s made money any way you can make it with an airplane and by the time he reconnects with Arrington in the early ‘80s he’s making it flying Colombian cocaine through the Gulf of Mexico and into the U.S. by the quarter ton.

His Colombian connections are a Bogota trafficker named Rafael “Rafa” Cardona Salazar and Max Mermelstein, a Spanish-speaking Brooklyn Jew who’s become the highest-ranking gringo in the Medellín cartel. Hetrick’s the key man who helps the Miami-based Mermelstein set up operations in California. Hetrick and his sons fly single-engine Cessna 210s to Colombia and bring them back loaded with cocaine.

Hetrick doesn’t tell Arrington all this right away. Hetrick is a master manipulator. Hetrick sees Arrington’s need for a father/mentor and feeds it. Hetrick talks about retiring and handing over his business to Arrington. By the time he tells Arrington what precisely that business is, Arrington’s in too deep to turn back.

Hetrick walks Arrington into a Los Angeles hotel room and introduces Arrington to Max Mermelstein as his right-hand man. Now the cartel knows Arrington’s name and his face. When Hetrick offers Arrington $50,000 to make a flight to Colombia for him, Arrington knows he can’t say no. A few days later he’s in the jungle outside Bogota watching cartel soldiers load Hetrick’s plane with coke.

Months go by. Arrington’s never alone long enough to run. He’s in Fort Lauderdale working on one of Hetrick’s boats when Hetrick asks him to drive the car to California. Hetrick’s been shopping for Rolls Royces in Florida and Arrington thinks Hetrick’s asking him to move a Rolls. When Hetrick tells him it’s actually a friend’s car, Arrington realizes what he’s being asked to do.

Arrington has $25,000 already — half of the $50,000 Hetrick promised him for the Colombia run. He figures he’ll drive the car and its cargo to California, collect another $20,000 from Hetrick, and disappear up the West Coast with it. One more job.

Arrington and an old surf buddy — in a memoir, In DeLorean’s Shadow, Arrington calls him “Sam”— meet Rafa Salazar’s cousin Rodrigo Restrepo at a Ft. Lauderdale motel. Restrepo brings them a blue Chevy Caprice-- “The most luxurious Chevrolet ever built,” the ads used to say. This one has an aftermarket addition: A secret compartment welded into the trunk. Inside the compartment are twenty kilos of cocaine. There’s nothing in the trunk but a spare tire and a large mesh bag of pineapples, put there to mask the acetone reek of the cocaine.

They’re about an hour out of Miami when they hear President Ronald Reagan on the radio promising to “do what is necessary to end the drug menace and cripple organized crime.” The U.S. government is stepping up the War on Drugs. Arrington used to watch Reagan on Death Valley Days as a kid. Arrington is betraying his childhood hero and his commander-in-chief in a single car trip. It’s all he can think about.

On the night of October 18, in a restaurant parking lot near the Van Nuys airport, Arrington springs the Caprice’s secret compartment for someone named Louie, who he understands to be an associate of Hetrick’s. Louie is actually a DEA agent named Gerald Scotti. Scotti verifies that the secret compartment is full of cocaine and suddenly the parking lot is full of men with guns.

For a few long seconds Arrington thinks he’s about to be murdered by rival dealers, until the red-haired man holding a revolver to Arrington’s head says “Federal agents — you’re under arrest.”

Arrington will later tell the court that no words have ever made him happier.

While this is happening, Hetrick is in Century City having dinner at La Cage aux Folles on La Cienega, where the floor show features L.A.’s finest female impersonators. His dinner companion is an undercover FBI agent named Benedict Tisa, although Hetrick knows him as “James Benedict,” a banker from the Bay Area. Hetrick is arrested in the parking lot around 11:15 PM, right after Arrington gets busted.

Hetrick flips on everyone, from DeLorean to Mermelstein. Mermelstein is arrested in 1985. His testimony helps bring down Rafa Salazar and Pablo Escobar and hastens the fall of the Medellin cartel as a whole. His book The Man Who Made It Snow may be the only autobiography to feature blurbs from four federal prosecutors. James P. Walsh — who also oversaw the case against John DeLorean — praises him as “the single most valuable government witness in drug matters in the country today.”

When he’s busted, Hetrick doesn’t contact DeLorean. The following day, when DeLorean walks into Room 501 at the Sheraton La Reina with with Tisa/Benedict and James Hoffman, he’s unaware that Hetrick is already in custody.

A man DeLorean knows as John Vincenza is waiting for them in the room. DeLorean’s understanding is that Vincenza launders money through Benedict’s bank. Nobody’s ever said it to him, but he’s pretty sure Vincenza is some kind of mobster.

“Vincenza” says he’s heard on the radio that DeLorean’s car factory in Belfast — which has been in receivership for eight months after being deprived of additional funding by Margaret Thatcher’s government — is closing down. DeLorean says there’s still a chance he can save the company if he can produce $10 million before Friday. This is a lie.

“You mean I'm too late?” says “Vincenza.”

“No,” DeLorean says. “You’re right on time. This is what they call in the nick of time.”

Vincenza is actually an FBI agent named John Valestra. James T. Hoffman is a federal informant who’s collected around $32,000 in salary from the government to make a case against DeLorean and Hetrick. The rooms on either side of 501 are full of law-enforcement officials from a joint FBI/DEA task force. This is the denouement of a project called Operation Full Circle. There’s a hidden camera pointing at DeLorean as he sinks into an armchair facing the door.

Vincenza/Valestra offers DeLorean a glass of wine. DeLorean says sure, he’ll have some: “Dismal day.”

“I don’t need much,” DeLorean tells the Detroit Free Press in 1974. “I can live on $60,000 or $70,000. I could lay around on some beach for the rest of my life, but that’s not my style. I’m running because it turns me on.”

When he says this he’s already famous. He’s the automotive iconoclast who walked away — or so goes the official story — from a $650,000-a-year job at General Motors two years earlier. DeLorean lives in an America that will wait forever for a white man to make good on his potential. He is a hotshot full of promise at the tender age of 49.

He tells reporters he’s hustling by choice but it looks a lot like he misses that $650,000 income and will do just about anything to replace it. He hooks up with Roy Nesseth, a onetime car salesman whose office is a payphone at a bar on the Pacific Coast Highway. They start doing deals together. They share an unwillingness to give a sucker an even break. Years later, reporters digging into DeLorean’s mid-Seventies escapades will detect a fairly obvious pattern. They’ll speak to the people DeLorean partnered with, then burned, with Nesseth as his proxy — the inventor from Phoenix, the rancher from Idaho, the car dealer from Wichita.

“He uses the mystique to put the deal together ... and then he puts the rape in. The guy is a demon underneath.”

But none of that really comes to light until long after the British government gives DeLorean a pile of taxpayer money to play with.

The car dealer, Gerald Dahlinger, lets DeLorean quietly buy into his dealership, then watches in horror as DeLorean and Nesseth use the business to run up kingly debts. Dahlinger tries to convince his bank that something insane is happening to him, and when that fails, he ends up walking away from Wichita entirely. He moves to Florida, leaving nearly everything behind, including a car Delorean borrowed from him in 1976 — a Mercedes 300 SL, the kind with gull-wing doors.

“He uses the mystique to put the deal together,” Dahlinger later tells New York magazine, “and then he puts the rape in. The guy is a demon underneath. I tried to tell people, but I gave up talking, because nobody would listen.”

While all this is happening, DeLorean is plotting his return to the car business and his revenge on General Motors. In 1974 he goes to Turin, Italy, where Giorgetto Giugiaro — the legendary car designer and chief stylist of the Lamborghini — sketches him what will become the DMC-12. Giugiaro envisions a sleek wedge of stainless steel. It looks a little like a Lamborghini and a little like the Tapiro, a concept car Giugiaro designed for Porsche a few years earlier. It’s unlike anything else on the road. It will still look futuristic even after they sit on the design for years while trying to scrape together the money for the factory.

Delorean wants a rear-engine car with gull-wing doors and a stainless-steel body. His other demands are mostly conceptual. DeLorean insists the DMC-12 come with a trunk big enough for a set of golf clubs, reportedly reminding his team, “This car is aimed at a particular section of the market — the horny bachelor who’s made it!” DeLorean’s old GM colleague Bill Collins leads the engineering design process at first. But in 1978 DeLorean enters into a partnership with Colin Chapman, the founder of Lotus Cars and its Formula 1-dominant racing team, Team Lotus. Collins leaves for a job at American Motors and Chapman’s team redesigns the car from the outside in.

In September 1978, the DeLorean Research Limited Partnership collects $12.5 million from a group of high-profile investors, including Sammy Davis Jr., Rosemary’s Baby author Ira Levin, Pan Am chairman Juan Trippe, the country singer Roy Clark, and the chairman of Wendicorp, the parent company of Wendy’s. The money is ostensibly for “research and development.”

In October 1978, Colin Chapman and John DeLorean meet in Geneva, Switzerland and begin moving money into accounts controlled by a firm called GPD Services. GPD is chartered out of Panama and its headquarters is in the apartment of Marie-Denise Juhan, a car importer and dealer in precious stones. Juhan’s husband, Jaroslav “Jerry” Juhan, is a former Porsche race-team driver who’ll be described after his death in 2011 as “a knowledgeable intermediary with the mysterious world of Swiss banking.”

In late 1978 and early 1979, the DeLorean Research Limited Partnership pays GPD nearly $18 million. The money is supposed to go to Lotus for research and development on the car, with GPD as the intermediary safeguarding Lotus from taxes and other liabilities. But according to John DeLorean’s 1985 fraud indictment, only $137,167 actually goes to Lotus. The rest of the money disappears, although no one notices at the time — even the accounting firm Arthur Andersen, which audits DeLorean’s business in both 1978 and 1979 and finds nothing amiss.

“TAKING ON DETROIT: JOHN DELOREAN SAYS HE’LL SHOW INDUSTRY HOW TO BUILD CARS,” reads a January 1979 headline in The Wall Street Journal.

“His novel, dealing with the nuclear-arms race,” writes the Journal, “remains unfinished and long-neglected.”

The Belfast factory opens in 1980. It’s clean and modern — “as neat as an IBM computer installation,” William Haddad later writes — and full of hope. It has separate entrances for Protestants and Catholics. One thousand workers file into the building. They gather around what looks like a prototype DMC-12. They put their hands on the car and realize it’s made of wood.

That fall the filmmakers D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus shoot a documentary about the factory. Later, a reporter asks Pennebaker what he remembers about DeLorean and Pennebaker says that “he was so tight he twitched.”

DeLorean doesn’t like Belfast. He’s worried he’ll be targeted for abduction or worse. It’s not a farfetched fear. The kidnapping rate in 1970s Ireland is second only to Sicily’s, and flashy foreign businessmen are a particularly common target. DeLorean hears about the Secret Service making Henry Kissinger a bulletproof leather trench coat and bugs his staff to get him one.

He almost never stays the night in Belfast. He flies into London on the Concorde and stays at the Savoy, or the Ritz, or the Connaught. He takes a helicopter to and from the factory. He’s running a startup on someone else’s money and should probably be trying to keep his overhead low. But this is the ‘80s, so there’s no romance attached to the notion of the garage-band entrepreneur yet. And this is John DeLorean, who was once quoted as saying “I’d rather be sterilized than go second-class.” He’s a poor boy at heart. His tastes run luxurious. He has to go Sharper Image, not Whole Earth.

In New York the DeLorean Motor Company rents two stories in the Bankers’ Trust Building on Park Avenue. They take it over when Xerox moves out. The lobby has marble floors. The glass front desk is big enough for 10 receptionists. DeLorean’s personal office has a view of Central Park, only partly obscured by the 50-story International Style tower at 59th and 5th that houses the New York offices of General Motors.

“The whole thing was geared as if it was GM,” former DeLorean executive J. Bruce McWilliams later tells The New York Times. “Instead of marvelous facilities on Park Avenue, it should have been a loft on 11th Avenue.”

In his office John hangs a poster-size photograph of himself — shirtless in jeans, seated on a rock with Zachary, looking thoughtfully at crashing surf. Visiting on behalf of GQ, writer Anthony Haden-Guest clocks the caption. A Joni Mitchell line from “Both Sides Now”: It’s life’s illusions I recall.

DeLorean pays himself a $78,100 “locale adjustment” fee to move his family from Detroit to New York. They settle in a 20-room Fifth Avenue duplex in a 1930s apartment building designed by the legendary Rosario Candela. The New York Observer will later call it “the most pedigreed building on the snobbiest street in the country’s most real-estate-obsessed city.” Past and present tenants include Charles R. Schwab, Robert Wood Johnson, Elizabeth Arden, and Rupert Murdoch. His real-estate portfolio already includes La Cuesta de Camellia, a ranch on 17-acres of country-club land in the Pauma Valley near San Diego, complete with horse stables, an aviary, and a hot tub that seats ten. In 1981 he’ll level up again, paying a record-breaking $3.5 million for Lannington Farm, a 430-acre spread in the rolling hills of Bedminster, New Jersey.

The company will eventually put money towards chauffeurs and servants, cars for Cristina Ferrare and her brother, upkeep on his properties, and a expensive collection of art, much of which ends up stacked in the halls of the office. The company pays John and Cristina’s friend Maur Dubin — described by People magazine as “a short, bald, egregiously demonstrative middle-aged interior decorator who affected a full-length mink coat” no matter what the season — to renovate the office, at at a stone-carver’s pace.

DeLorean is living more lavishly than in his General Motors salad days and the British are footing the bill. His relationship with his benefactors grows more tense when Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government wins the general election in 1979 and grudgingly inherits DeLorean’s deal with the Northern Irish Development Association. The last thing on Thatcher’s mind is helping Belfast help itself.

John hires a British secretary named Marian Gibson to put the British government’s emissaries at ease when they visit the DeLorean Motor Company’s beautiful offices. Before long she’s his de facto office manager. She controls access to John. She keeps the checkbook. John writes every memo in longhand on the graph-paper notepads he’s used since his days as an engineer, and Marian types them up.

Haddad’s book portrays John circa 1981 as Prince Hamlet stabbing at the curtains. John thinks the IRA’s coming for him. John thinks a British “hit squad” is coming for him. John asks Haddad — a former assistant to Robert Kennedy — to put him in touch with Israeli intelligence, so he can pitch them his plan to pin a fake nuclear-terror threat on “Arab radicals” as an excuse to seize the Saudi oil fields. John hassles Haddad about the bulletproof coat.

John’s inner circle is contracting. But there’s only one voice he really trusts. In his autobiography he calls her “Sonja.” She has a little storefront off 55th Street. Her sign says “PALM READER AND ADVISER.”

John first meets Sonja through Cristina, who goes to her when she and John have been struggling without success to conceive a child. Cristina explains her problem to Sonja. Sonja gets up, fills a Mason jar with tap water, and places it under Cristina’s chair. They keep talking, and then at the end of the session, Sonja shows Cristina the Mason jar again, only now it’s full of blood.

According to John’s autobiography, Cristina comes home, tells John this story, and asks him for $10,000 to give to Sonja for further assistance. John obliges. Their daughter Kathryn, John’s first biological child, is born in 1977.

John starts seeing Sonja privately. He doesn’t make important decisions without consulting her. He gives her money and she tells him, in a faint New York accent, that he’s merely being tested, that everything is going to be okay.

The 1980 American Express Christmas catalog features an $85,000 limited-edition DeLorean DMC-12 electroplated in 24-karat gold.

The 1980 American Express Christmas catalog features an $85,000 limited-edition DeLorean DMC-12 electroplated in 24-karat gold. It looks like something a decadent prince might buy and get bored of and shoot up with a long rifle that is also plated with gold. In a sense the gold DeLorean is the quintessential DeLorean — an absurdly expensive Christmas toy for hypothetical rich people buying things on credit. Only 100 of them are offered in the catalog; only two are ever sold. The Daily Mirror claims Rod Stewart bought one, which turns out not to be true.

On April 20, 1981, a cargo ship leaves Belfast Harbor for Long Beach, carrying the first DeLoreans that will be sold in the United States. As redesigned by Chapman’s team, the DMC-12 is essentially a Lotus in a stainless-steel shell. DeLorean has sold the world on the idea of a so-called “ethical sports car,” but the car he actually delivers is neither as groundbreakingly safe nor as pace-settingly fuel-efficient as he’s promised it would be.

It’s underpowered and handles poorly. At an auto show in Cleveland a visitor is trapped in a DeLorean for over an hour when the gull-wing doors won’t open. There’s a design flaw in the electrical system that cripples battery life, as DeLorean’s pal Johnny Carson discovers when his new DMC-12 breaks down shortly after he drives it off the lot. And because of what it’s cost the company in time and money to build the DMC-12, they have to price it like a luxury car. The retail price has ballooned to around $25,000, which in 1981 gets you most of the way to a decent Porsche.

They sell, but not fast enough.

The cars don’t matter. They start out as an idea DeLorean can raise money behind and will become an asset he can trade on as the walls close in. That’s all they ever are, no matter what their present-day cargo cult might tell you. They’re not the future of anything. They’re standard parts in a beautiful shell. The man who puts his name on the cars is the future. A hungry ghost borrowing ever-more-boldly against ever-more-notional success. He understands that business in America is whatever you can get away with. He builds himself a gilded life and finds bigger and bigger suckers to pick up the tab.

Is this what Marian Gibson begins to see?

Gibson falls out of John’s favor and is put on Haddad’s desk. She’s told to read the Hansard — transcripts of debates in Parliament— and flag references to the DeLorean project. The references aren’t laudatory. Marian has a comprehensive understanding of John’s spending habits and the company’s finances. She begins to suspect that John is up to something. One night Marian Gibson slips into the DeLorean offices and leaves with two shopping bags full of documents, including duplicates of every memo she’s ever typed for John. At minimum, the documents suggest that the company is mismanaging the British government’s money; one memo accuses a DeLorean exec named Chuck Bennington of blowing thousands at Harrods on gold-plated faucets.

There’s a plan in the works to restructure the company and take it public as a new umbrella corporation, the DeLorean Motors Holding Company. The proposed stock offering will personally enrich DeLorean, the company’s majority stockholder, by around $120 million, whereas anyone holding only stock options — like the car dealers who’d invested early in exchange for first crack at the rights to sell DeLoreans, and many of the DeLorean Motor Company’s own executives — will be left with next to nothing.

The British government, which acquired two seats on the board of the DeLorean Motor Company in New York in the NIDA deal, will lose those seats under the new plan — and with it their ability to watch what DeLorean’s doing with their money. They’ll get 3.6 percent of the new holding company and stock worth $8.4 million, a fraction of the nearly $150 million they’ve already put on the table. DeLorean is about to make himself a multimillionaire on paper and marginalize his partners.

Marian doesn’t contact NIDA. She takes a plane to London and a train to Macclesfield and shows them to a Tory MP named Nicholas Winterton, who agrees that someone should look into it and promises to take action. So Marian goes home to wait for Scotland Yard to do something. When nothing happens for days, then weeks, she sits down with a Fleet Street reporter named John Lisners instead.

Lisners sells his story to News of the World and spends three days in New York interviewing Gibson. A London News of the World reporter calls DeLorean for comment, tipping him off that he’s been betrayed from within. DeLorean handles this in the classiest possible way, by sending Maur Dubin in his mink to deliver a message to Marian on gold-leaf stationery.

JOHN IS NOT ANGRY OR BITTER. HE JUST WANTS TO KNOW WHY YOU ARE DOING THIS, MARIAN. HE JUST WANTS TO TALK TO YOU.

That afternoon News of the World kills Lisners’s piece, on orders from Rupert Murdoch, DeLorean’s neighbor. Murdoch will say later that he and Cristina DeLorean had only a nodding, elevator-riding acquaintance, and that he didn’t know John DeLorean at all, and that the piece relied more heavily on the word of a disgruntled employee than one with whom Murdoch was comfortable. But when Lisners sells his DeLorean piece to the Daily Mirror, it’s Murdoch who puts DeLorean in touch with the fearsome British libel lawyer Lord Arnold Goodman.

DeLorean works the press. He calls Gibson troubled and unstable. He refers to her as a typist. He calls Lisners an “unemployed writer” with an agenda. He calls the allegations that he’s ripping off the British government “asinine.” He gets the favorable headlines he’s looking for. He invites a BBC crew into his New York apartment and Cristina cries on camera. He flies to into Heathrow and deplanes wearing a turtleneck under a double-breasted blazer. He tells reporters that Gibson and Winterton are, respectively, “a troubled, nervous old typist” and “an MP… never known for his intellectual clarity.” He flies to Belfast and hints at a foreign plot “to destroy Ulster’s proudest achievement.” He announces plans to sue Lisners and the paper for $250 million in damages.

The Scotland Yard inquiry finds no wrongdoing. But the scandal delays the DeLorean Motor Holdings stock offering. John’s $120 million evaporates. The company survives just long enough to run out of money. On February 19, 1982, DeLorean Motor Cars Ltd. — the UK manufacturing arm of John DeLorean’s car business — is put in receivership by the British government. The company remains technically in business while the receivers determine if any part of it can be salvaged. Sir Kenneth, the former Lord Mayor of London and a partner in the storied insolvency firm Cork Gully, is in charge of that process. In British financial circles, Cork is known as “Mr. Receiver,” or more simply as “The Undertaker.”

John holds a press conference at Claridges Hotel in London, tells a New York Times reporter that he’s “delighted” by the news, then catches the Concorde back to New York. “We came out largely unscathed,” he tells the Times later that day. “The government has the problem, and we have the fun end of the business.” He claims the receivership will immediately wipe $130 million in debt off the company’s books. John’s new business associate Sir Kenneth Cork characterizes this last assertion as “codswallop.”

So begins a months-long dance. Cork sets deadline after deadline while DeLorean blusters and wheedles and stalls. More than once, he’ll tell Cork he’s found an investor to save the firm. Usually it’s an Arab. Sometimes it’s an Arab head of state. The dollar amount the Arab is prepared to invest never changes — it’s always $30 million.

“Surely to God,” Cork says to DeLorean during one of these conversations, “you could find the grace to vary the figure every now and again, if only for appearance’s sake.”

For a dead man walking, John still gives good quote. The week the receivership is announced, a long-in-development line of DeLorean-branded men’s toiletries finally goes on sale. DeLorean tells the New York Post, “We’re thinking about calling it ‘A Scent for Losers.’”

DeLorean writes checks to Sonja, his psychic, and Sonja tells him to keep the faith. He pops Seconals to fall asleep at night. He’s also using a painkiller called 222, which contains aspirin, caffeine, and codeine and is only legal in Canada. During the day he pounds coffee and lobbies potential investors.

“We’re thinking about calling it ‘A Scent for Losers.’”

On June 29, 1982, he takes a call from James T. Hoffman.

Hoffman lived for a short time near DeLorean’s ranch in Pauma Valley, California. Hoffman will later claim they were good friends, and that his first call to DeLorean was of a purely social nature. DeLorean will contend that while their sons were acquainted, he and Hoffman spoke on only one occasion — around Easter 1980, for a few minutes in DeLorean’s driveway.

“Parts of the [1980] conversation were quite memorable,” DeLorean will tell Rolling Stone years later, “because [Hoffman] told me he was in the used-airplane business. And then he related some story about repossessing a plane from some banana republic and having the soldiers shooting at him.”

DeLorean will say they had no further contact until two years later, when Hoffman called him at work. He’ll say that during this call, Hoffman offered to put him in touch with some investors, and that until September — when Hoffman makes overt reference to his involvement with the “Colombian coke program” during a meeting with DeLorean — DeLorean believed his neighbor and his contacts were looking to make a legitimate business deal.

When Hoffman, a longtime federal informant, tells the story on the witness stand at John DeLorean’s trial, he will say that when he spoke to DeLorean that day in June, DeLorean asked Hoffman to call him back at home. He’ll say that when they spoke the following day, DeLorean said he had $2 million to invest, asked if Hoffman could help him turn that money into $40 or $50 million via his “connections in the Orient” — and that DeLorean did not balk when Hoffman told him he knew of a way to do that which “would not be blessed by Baptists or the Pope.”

PART THREE

Knee Deep in Monkeys

“What if we don't succeed?”

“We must succeed!”

In 1914 Henry Ford announces that he’ll begin paying the workers at his auto plant the previously unheard-of sum of five dollars per day, to help ease their adjustment to the physical and mental pressures of a new manufacturing method called the assembly line.

The raise is actually a bonus, extended only to workers whose off-hours conduct meets behavioral standards set by Henry Ford. The former dean of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Samuel Marquis, heads up the Ford Motor Company’s new Sociological Department, whose investigators periodically spot-check the homes of Ford employees for evidence of turpitude.

“They asked the wives how much money their husbands saved, how much they brought home, whether they drank, whether they had any domestic difficulties,” Henry Ford’s associate Harry Bennett would explain years later. “If a workman had kept out of his pay a few dollars for a crap game or a glass of beer, he was in trouble.”

A former Navy man and prizefighter, Bennett meets Ford by chance in the 1920s and gradually becomes his enforcer, spymaster and confidant, the Rasputin of River Rouge. When Ford puts Bennett in charge of maintaining order at the plant — which mostly means suppressing union activity — Bennett quickly eliminates the Sociological Department and replaces it with the Service Department.

They’re goons. Ford production manager Charles Sorensen once described them as “a strange collection of broken bruisers, ex-baseball players, one-time football stars, and recently freed jailbirds” who “never looked or acted like Ford men.” Some of them are soldiers or better in Detroit’s various thriving mafia families; some of them are members of the Black Legion, a splinter group from the Ohio Ku Klux Klan.

Ford Service routinely visits the homes of Ford employees to search for stolen tools or other evidence of malfeasance. The visits tend to double as shakedowns to intimidate troublemakers, particularly union men. John DeLorean’s father Zachary is one of those men. In his 1985 autobiography, DeLorean remembers “hiding wide-eyed behind my seething, long-underwear-clad father who stood helpless with clenched fists as the billy-club-armed goon squad ransacked our tiny house.”

The goons find no tools. DeLorean tells the story as proof that his father was a stand-up guy when he wasn’t drunkenly abusing DeLorean’s mother, Kathryn Pribak DeLorean. He doesn’t make it sound like a moment that shaped the rest of his life.

But imagine.

Here are a bunch of wiseguys and palookas granted paramilitary authority by the Ford Motor Company, tossing John DeLorean’s father’s house. Here’s John DeLorean cowering behind his father. Here, in the person of Harry Bennett’s thugs, is the power of the American auto industry, revealed in its functional limitlessness to John DeLorean for the very first time. Here are men who can bring to heel his angry god of a father.

DeLorean goes to work for the only car company bigger than Ford and flouts its rules wherever he can. He’s avenging the old man and outdoing him. He tries to reap every benefit the auto industry can offer him while refusing to become the kind of man the industry wants him to be. And when that proves untenable he goes off on his own, to take on the Big Three from the outside — and secure for himself the life he’s always believed he deserves.

Except it’s a one-sided fight. GM and the rest of the Big Three don’t destroy John DeLorean. They don’t because they don’t have to. They know the odds are against him, because no matter how much money he convinces some foreign government to give him, his stake will run out eventually, and long before theirs does.

GM and the rest of the Big Three don’t destroy John DeLorean. They don’t because they don’t have to.

Instead it’s two governments that finally take him down. Unable to see the wisdom of fighting the IRA with manufacturing jobs or of paying John DeLorean to create those jobs, Margaret Thatcher cuts off his money supply. Then, on the word of a professional informant named James Hoffman, federal law-enforcement officials in the United States include DeLorean in a cocaine-trafficking sting. It’s been suggested that the American and British authorities actually collaborated to undo DeLorean — that the receivers from Cork-Gully were instructed by the British government to let DeLorean push deadline after deadline, so that he’d still have a company to save and an incentive to participate in a potentially lucrative drug deal. They let him dangle, so that the Americans can finish what they’ve started.

What they’ve started goes like this.

In the fall of 1981, around the time Marian Gibson is collecting her shopping bags of DeLorean documents, James T. Hoffman is working off a cocaine-smuggling charge by acting as the roper in a series of government sting operations. When he goes to court to testify against the objects of these stings he’s escorted by federal agents. One day his escort is a DEA agent named Gerald Scotti. They get to talking. Scotti later testifies that Hoffman offered to “deliver” a new, high-profile target to the DEA — his old neighbor, the playboy automaker John DeLorean.

“He told me, he said, ‘Listen, this guy is in a lot of trouble now with his auto company,’” Scotti tells the court. “And I remember he was bragging because he was indignant about the fact that I didn’t believe him, and he kept saying, ‘I’m telling you, Scotti, I’m going to deliver John DeLorean to you guys.’”

Hoffman’s federal minders don’t take him seriously at first. They tell Hoffman to focus on the task at hand. They’re closing in on William Morgan Hetrick, a pilot and aviation-firm proprietor from Mojave, California who appears to the Feds to be sitting on a suspicious amount of cash, makes frequent trips to and from Colombia — and happens to be a former employer and business associate of James T. Hoffman.

But Hoffman decides to start working DeLorean on spec. They talk on the phone. Then in July — the month Car & Driver teases a story about DMC’s financial travails with a cover image of chickens coming home to roost in an up-on-blocks DeLorean — they meet in person for the first time, in the bar at a Marriott in Newport Beach.

None of these calls or meetings are recorded. DeLorean will later claim that Hoffman never mentioned drugs. Hoffman will tell his superiors at the FBI that DeLorean did. After the Newport Beach meeting, the FBI opens a case file on DeLorean. The Hetrick investigation becomes Operation Full Circle. Its targets are William Morgan Hetrick and John Z. Delorean.

In August, the FBI agent named Benedict Tisa — whom DeLorean will soon come to know as “James Benedict” — writes a briefing to his team.

“In as much as JZD [DeLorean] wants to participate in a narcotics transaction,” it reads, “as per CI [Hoffman], to realize profits to finance company with initial $2M, and WMH [Hetrick] has offered cocaine, let JZD buy from WMH while attempting to bring WMH’s offshore money into the U.S. as a temporary loan/investment until narcotics are moved by Confidential Informant. This will allow seizure of illegal profits and narcotics, if timing is right.”

How much JZD actually “wants to participate in a narcotics transaction” is open to interpretation. At trial, DeLorean’s lawyers allege that John failed to realize he was being pulled into a drug deal until it was too late to back out. In his autobiography, DeLorean depicts himself as the kind of desperate civilian you might find in a John D. MacDonald novel, in too deep with the wrong guys, begging for help from Travis McGee:

“Later on that evening I took my pills and dropped into fitful slumber. The phone awakened me, and I groggily answered. It was Hoffman. I was instantly awake, my stomach in knots, my breathing rapid. My heart racing. No more, I told myself. No more. I wanted it all to end. I wanted Hoffman to leave me alone. It was as though I was in the midst of one of those horror pictures where each time the monster is struck down, it returns bigger and stronger. Only this was real life. This man was flesh and blood… My movie was not going to end.”

“You know too much — you can’t get out,” DeLorean claims Hoffman told him on that call. “I’ll send your baby daughter’s head home in a shopping bag.”

And yet in the days and weeks after this conversation supposedly takes place, even he and Hoffman are back to talking congenially, like nothing strange has happened.

“You know too much — you can’t get out ... I’ll send your baby daughter’s head home in a shopping bag.”

DeLorean spends that summer and fall sleepwalking into a trap. He talks to Hoffman and “Vincenza” and Hetrick on the phone and in hotel rooms around the country. They’re as intimate as assassins. They develop a shorthand. Hetrick, who used to use his plane to transport exotic animals, refers to contraband as “monkeys.” In the fall, he warns DeLorean that once they set the buy in motion, there’s no turning back, that it won’t be long before his connection in Colombia calls and says “We’re knee-deep in monkeys.” Before long DeLorean is making winking references to “monkeys” as well.

All of this is caught on tape and video. During one hotel-room meeting between Hoffman and DeLorean, there are so many law-enforcement officers eavesdropping in the next room that the smoke from their cigarettes triggers the fire alarm.

The deal takes a while to hash out. Hetrick doesn’t trust Hoffman. They had a falling out over a business deal years ago, and on the wiretaps Hetrick refers to Hoffman as a brilliant snake who’d “fuck his own mother if he’d get a quarter for it.”

More importantly, Hetrick reads the Wall Street Journal. He knows DeLorean’s business is on borrowed time. When “James Benedict” tries to entice him into the deal with DeLorean Motor Company stock or a seat on the board, Hetrick is underwhelmed.

“Irishmen are better at making whiskey and digging potatoes than building cars,” he tells Benedict at a meeting in September. “Every [Delorean] I’ve seen looks like shit. You can throw a cat through the cracks in the doors. It’s not a well-made car.”

There’s another problem: DeLorean is supposed to put up $1.8 million toward the purchase price of the coke. DeLorean doesn’t have $1.8 million. In September he admits as much to Tisa/Benedict, although he claims it’s because his nonexistent Irish Republican Army contacts have banked the money with the receivers. “All my IRA talk was nonsense, of course,” he writes later. “I just prayed it would work.”

An actual drug deal, whether for a dime bag or a planeload, would doubtlessly have ended right here. Instead, Benedict calls DeLorean back a few days later and agrees to loan him the money. As collateral, DeLorean offers up what’s left of the DeLorean Motor Company’s assets — car parts, office furniture, and 40 inventory DMC-12s, against the value of which he’s already borrowed $10,000.

And when DeLorean finds himself in a tight spot with the receivers from Cork Gully, he brings the issue to the quote-unquote mobsters he’s working with, who agree that once they resell Hetrick’s cocaine, they’ll invest some of the profits in DeLorean’s company, rescuing him from foreclosure. In return, DeLorean agrees to sign over to his partners the one thing he has left — a controlling interest in his company.

Somehow the fact that the mob still wants DeLorean involved in the deal despite his inability to put any money into it — with nothing but a deeply troubled car company as collateral — does not raise a red flag for DeLorean. In late September, DeLorean calls Hetrick and says he’s ready “to go ahead with those monkeys you had up in San Francisco.” Hetrick calls Mermelstein, who balks at his request for 50 kilos. Hetrick calls Salazar. Salazar calls Mermelstein a few days later and tells him he’s doing the deal, but for only twenty kilos — and that the buyer is the auto-industry big shot who makes that new stainless-steel car with the butterfly doors.

The cocaine deal is yet another business venture into which DeLorean has not put a dime of his own money. The government believes his agreement to hand over control of his company constitutes proof of his willingness to participate. Except DeLorean hasn’t actually arranged to give them DeLorean Motor Cars Limited or the DeLorean Motor Company. He’s agreed to give them control of DMC, Inc., a dormant U.K. shell company that has no assets and is now controlled by the receivers at Cork-Gully.

His lawyers will later argue that this was an attempt by DeLorean to avoid actual lawbreaking without incurring the mob’s wrath by pulling out of the deal. It’s also possible that he sees this as a way to handcuff his Mafia associates to the British government and walk away — that he believes he’s about to win. The night before he leaves for California, he suggests as much in a letter to his attorney, Thomas Kimmerly.

“TOM,” the letter begins, “I’M GOING TO L.A. TOMORROW TO ACCOMPLISH A MINOR MIRACLE! I WILL HAVE INDUCED ORGANIZED CRIME TO DONATE $10,000,000 TO REOPEN THE BELFAST PLANT — AND WHEN THEY FIGURE IT OUT, THEY CANNOT DO ANYTHING ABOUT IT!”

The letter is handwritten on graph paper; he seals it in a DeLorean Motors Holding Company envelope and instructs Kimmerly to open it in the event of his death.

Since Vincenza is not a real mobster and this isn’t a real drug deal, the government doesn’t actually put any money into DeLorean’s businesses. They stonewall the receivers in the days leading up to the L.A. meeting. On October 19, 1982 DeLorean flies to California. There are three undercover FBI agents seated behind him on the plane. The final deadline for DeLorean to deliver an infusion of capital and save the company comes and goes while he’s in the air. His company will dissolve, his factory will close. Sacked workers will stand on the hoods of parked DMC-12s outside the factory waving picket signs. Eventually the Irish will take the massive cast-iron tools that once bent steel into the shape of DeLorean cars and sink them in Kilkieran Bay off Galway to anchor nets for salmon fishing.

DeLorean lands in Los Angeles around 2:25 p.m. He is carrying no luggage.

James T. Hoffman and James Benedict pick him up in a white Cadillac Seville. They drive to the Sheraton Plaza la Reina hotel, just around the corner on West Century Boulevard.

It’s a clear fall day in Los Angeles. Within minutes, John is sitting in a chair in Room 501.

“Let’s show John what we’re talking about,” says John Valestra. “This is gonna be like a magic act.”

Hoffman clears the coffee table. Benedict goes to the closet and produces a suitcase full of cocaine. Hoffman tells DeLorean the coke will generate “not less than four-and-a-half million” once it’s sold.

DeLorean hefts a bag of coke and laughs.

“It’s better than gold,” he says. “Gold weighs more than that, for God’s sake.”

They laugh and toast to all the money they’re about to make. DeLorean chuckles in a way that won’t play well in court, although in his book he chalks it up to panicked euphoria. It was really a drug deal, thank God.

“In the madness of the moment,” he writes, “I had never been happier. My carefully constructed world — my company, my pride, my future — had been shattered, yet I was grinning like a fool and joining in the toast.”

Then an FBI agent named Jerry West walks into the room, trailed by a DEA agent named Jose Aguilar.

West looks at DeLorean and says “Hi. John?”

John is escorted from the hotel in handcuffs. He’s eventually charged with eight felonies related to cocaine smuggling and held on $5 million bail. In jail, DeLorean plays volleyball with his fellow inmates and reads the Bible in his cell. He’s a tall man — 6’4 — so he stands on the floor with the Bible open on the top bunk. One night as he’s doing this, God moves over the face of the waters separating the San Pedro harbor from Terminal Island and finds him there. God’s love pours over him like an indestructible robe of light and honey.

DeLorean liquidates a slew of assets to make bail, including his stake in the New York Yankees. The DeLoreans spend the holidays in Vail, skiing with the kids at Christmas and ringing in the new year with Henry and Ginny Mancini. Steve Arrington — the courier Hetrick paid to transport John’s cocaine from Miami to California — spends the last hours of 1982 in Unit J-3 on Terminal Island, dreaming of the wind in the bamboo forests of Waimea. This is the difference between being John DeLorean and being a regular person.

In the summer of ‘83, John and Cristina are baptized in the pool behind DeLorean’s New Jersey mansion. The born-again ex-Nixon aide Charles Colson advises DeLorean on his conversion. In the fall an office supervisor at one of the law firms working on DeLorean’s defense leaks the surveillance tapes of DeLorean’s bust to the porn kingpin Larry Flynt. Flynt pays the man $5,000, although he goes on to claim it was $25 million. Flynt — lately born-again himself, after a would-be-assassin’s bullet left him paralyzed from the waist down — slips the tape to 60 Minutes producer Don Hewitt, a onetime friend of the DeLoreans, and on October 23, 1983, the footage airs on the CBS Sunday-night news broadcast.

Citing the broadcast’s potential impact on the jury pool, Judge Robert Takasugi delays the trial six months. In the meantime, Flynt becomes a sideshow. A few days after the CBS broadcast, Flynt summons reporters to the lawn of his Bel Air mansion, produces a boom box, and plays them what he says is a tape of James Hoffman threatening John DeLorean. The audio quality is poor but Flynt helpfully provides the reporters with a transcript, in which Hoffman tells DeLorean that his young daughter could “get her head smashed” if DeLorean refuses to go ahead with the deal.

The tape disappears from the boombox while Flynt is giving reporters a tour of his mansion. When Takasugi drags him into court, Flynt refuses to turn over the tape or reveal who gave it to him. This standoff culminates in Flynt returning to Takasugi’s courtroom wearing only a bulletproof vest, an Army helmet, a Purple Heart, and an American flag (which he’s wearing as a diaper).

He’s brought with him $10,000 in crumpled bills to pay a contempt-of-court fine. Takasugi orders him to count out the money in an office down the hall from the courtroom. Later that day, an FBI agent named Jerry West finds Flynt asleep on the floor. A brief struggle ensues between the FBI and Flynt’s security team. Flynt later pleads guilty to wearing an unauthorized Purple Heart. In return, the government agrees not to charge him with desecrating the flag. He also admits to the court that his supposed DeLorean tape is a forgery.

Jury selection takes two weeks. DeLorean’s attorneys — Howard Weitzman, Don Re, and their associate Mona Soo Hoo — dismiss dozens of candidates for potential bias. Re expresses doubt that after the 60 Minutes broadcast, “an impartial jury, to which John is entitled, can be found.” But eventually six women and six men are seated, and the trial begins on March 5, 1984. There are more than 100 seats for press in and around the courtroom.

The prosecution shows the jury footage of John DeLorean in San Carlos, meeting Tisa/Benedict in a real bank manager’s office which the Feds have staged as if it’s Tisa’s own. The jury hears DeLorean say Hoffman’s deal “looks like a good opportunity.” The prosecution quotes Allen Funt’s tag from Candid Camera, saying that John’s been “caught in the act of being himself.”

Weitzman counters with his own Hollywood metaphor, describing the tapes as being “produced, choreographed and directed to make DeLorean look guilty.”

The defense attacks James Hoffman’s credibility as a witness. Takasugi also questions Hoffman’s motives, citing a teletype message in which Hoffman demands to be paid a percentage of the value of the bust as “evidence…that [Hoffman] was a gun for hire.”

Don Re hammers Valestra on cross-examination. Valestra admits to revising and backdating his case notes. Weitzman hammers Tisa. Weitzman gets Tisa to admit that at no point did DeLorean put up actual money toward the drug deal. Gerald Scotti cries on the stand when it’s revealed that the government convinced Scotti’s friend and mentor to give testimony discrediting him as a defense witness.

Of his former colleagues’ malfeasance in pursuit of a conviction, Scotti says, “I thought there was a limit to it — a bottom to it. Now I’m not so sure of that anymore.”

Scotti quotes James Hoffman’s own words:

“I’m going to get John DeLorean for you guys… The problems he’s got, I can get him to do anything I want.”

In the course of 50 days of testimony, the defense never calls DeLorean to the stand — a rarity in entrapment cases. John eats carrots at the defense table, doodles elaborately in his case notes. The O in “Hoffman” becomes the belly of a fat, traitorous devil; the “V” in “Valestra” a snake.

Cristina appears in court each day to stand by DeLorean in clothes from an 18-piece wardrobe custom-made for her by designer Albert Capraro. At one point she’s admonished by Takasugi for mouthing curses at a prosecution witness. At one point she visits the press room to bum a cigarette and ends up granting an impromptu press conference. “In the beginning, I used to cry,” she says. “Now it rolls off my back.” She leaves John three weeks after the trial is over. They divorce in 1985.

The defense’s closing argument in United States v. DeLorean is a magic trick. It will later appear in the book Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury: Greatest Closing Arguments in Modern Law, alongside Vincent Bugliosi’s summation from the Charles Manson trial and William Kuntsler’s defense of the Chicago Seven.

Weitzman goes through every single recorded contact between John and the government or proxies thereof. He argues that John starts out as a desperate but legitimate businessman pursuing legal investment, and that once his new partners begin talking openly about drugs, he does everything he can to insulate himself from that aspect of the deal. He argues that there would be no drug deal if the government had not concocted one and pulled DeLorean into it.

What the evidence shows, Weitzman repeats again and again, is “that DeLorean was manipulated, DeLorean was maneuvered, DeLorean was conned, and that John DeLorean is a victim. John DeLorean, unfortunately for all of us, was the victim of the very people whose oath it was, whose purpose it was, to protect him from criminal activity.”

“John DeLorean was willing to take the money. You may not like that. You may not approve of that. You may think it’s a question of morality, but it’s not a crime,” Weitzman says.

On August 16, 1984, after less than 30 hours of deliberation, a jury finds DeLorean not guilty of all charges. DeLorean shouts, “Praise the Lord!” as the verdict is read.

Thirteen months later, a federal grand jury in Detroit indicts DeLorean on charges of fraud and racketeering, in connection with the disappearance of the money the DeLorean Research Limited Partnership gave GPD Services. The prosecution claims a portion of the initial $17.65 million was routed through banks in Zurich and Amsterdam and found its way to DeLorean’s Citibank account in New York, and that DeLorean subsequently used $8.9 million of these funds to buy a snow-grooming company.

In a 2013 book about the company’s rise and fall, former DeLorean Motor Cars executive Nick Sutton claims the $17.65 million “was split between Colin Chapman… and John DeLorean with the loose change going to Fred Bushell, the finance director of Group Lotus.” Sutton writes that after the receivers from Cork Gully discover that there’s money missing, they have one conversation with Chapman about it. In December 1982, Chapman flies to Paris, where he meets with Jaroslav Juhan, the Czech-born sportsman-turned-fixer who reportedly facilitated Chapman and DeLorean’s Swiss-bank arrangement. Chapman lands back at the Lotus factory airstrip in England on December 15th. The next day he dies of a heart attack, without giving a follow-up interview to the receivers. Bushell is convicted of fraud and fined £4.5 million for his role in the GPD affair. He spends three years in jail.

The Belfast judge who sentences Bushell asserts from the bench that Bushell, DeLorean and Chapman all “engaged in… bare-faced outrageous and massive fraud.” But in December 1986 — almost exactly four years after Chapman’s death — that Detroit jury finds DeLorean not guilty of 15 counts of fraud, racketeering and tax evasion.

In 1985’s Back to the Future, the first film of an eventual trilogy, an eccentric scientist modifies a DeLorean so that it can travel through time. Three years after the company’s collapse and two years after DeLorean’s drug trial, the mere mention of a DeLorean car is a laugh line. But the movie’s tremendous success soon overwrites the car’s infamy. The DeLorean comes to signify the ’80s the way a pink Cadillac represents the theme-restaurant ’50s. DeLorean himself is increasingly misremembered as a visionary whose ideas the world wasn’t ready for — Doc Brown in a three-piece suit. When the movie comes out, he writes a thank-you letter to screenwriters Bob Gale and Robert Zemeckis.

DeLorean spends the rest of his life in and out of court. He declares bankruptcy in 1999. His Bedminster estate is purchased by a Connecticut-based golf-course development partnership, who within two years will sell it to Donald Trump.