I hadn’t been in the sauna for long when I found myself sweating. Oven-hot air filled my lungs; my skin roasted. When I blinked, I could even feel the heat on my eyelashes, burning against my eyelids. My towel, tightly wrapped around my chest, was carefully covering every bit of skin, to avoid contact with the warm wood underneath. Around me, 100 naked, slippery, pink bodies sat side-by-side, knees spread, elbows crooked in positions of relaxed anticipation.

Casually, three men dressed in cowboy outfits — Stetson on top, chaps down below, grass in mouth, the whole deal — sauntered into the room, as if it were a saloon. Full of bravado, they opened up a treasure chest prop placed next to the sauna oven to reveal spheres of ice, which they then packed onto the scorching stones in the middle. It sounded a hiss of pain.

Did you know that your body can shiver from being too hot? I felt the temperature instantly step up a notch as a plume of steam rose into the air. The churning pop music, which had been playing this entire time, reached its drum-laden crescendo. Suddenly, these Polish cowboys simultaneously swung three towels overhead. A burst of hot air swished around me, as these three Aufguss Masters began their ritual.

I was sweating out the finals of the Aufguss World Cup, the week-long annual sauna event attracting thousands of wooden sweatbox enthusiasts from around the globe. All year, Aufguss Masters from Europe and beyond had been competing in their 12 national heats, and relegation rounds, in order to prove themselves for this challenge. Once they’d made it to the World Cup, things got tougher. Throughout the pre-rounds in the beginning of the week, just over 30 entries in both in the team and singles categories had been whittled down to eight in each, through expert judging of seven different criteria such as waving techniques, distribution of heat, and “team spirit.” Now, on the final day of the competition, those same judges would decide, from this pool of eight teams and eight solo competitors, who would win out and take home a large cardboard check (top prize is a few thousand Euros, down to a couple hundred for 8th place), as well as worldwide bragging rights.

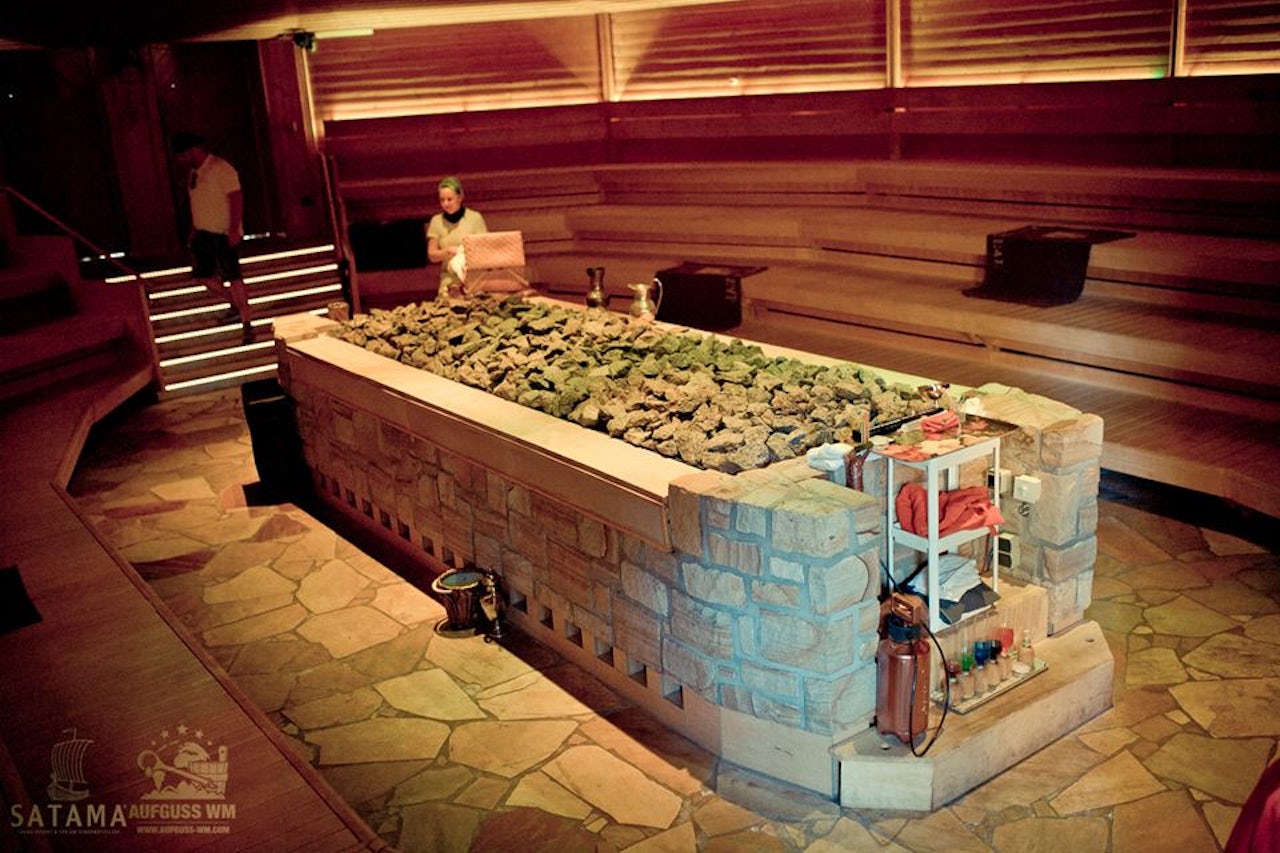

Translating to “infusion” in English, an Aufguss is a sauna ritual in which essential oils, water or other liquids are poured onto the hot stones, while the resulting steam is then used to “purify” the air via a complicated set of towel movements. The steam rises, the towel swings, and warm, scented air is swept onto your sweat-streamed skin, supposedly bringing a sense of well-being.

In a traditional, non-competitive setting, an Aufguss Master is the one who swings the towels and increases the heat, but they’re also in charge of the sauna guests’ experience, creating the maximum amount of relaxation to engage all the senses with scent, heat, meditative sounds — everything you’d expect from a practice designed to stimulate and unwind. At least, that was my experience in the run-of-the-mill, “classic” Aufguss experiences I’ve had in the past (they are a regular part of visiting the sauna in Germany, where I live). Eye-wateringly hot, yes, but also calming, and comforting in their simplicity.

“I can tell really quickly, if you have someone competing who doesn’t really know the sauna.”

At the Aufguss World Cup, on the other hand, Aufguss Masters take a bold, jazz-hands step beyond the tradition of the classic Aufguss, and instead perform something called a “Show Aufguss.” These "Well-tainment” (which, as the spa’s brochures, Facebook page and website informed me, is a registered trademark) competitions are complete with bright lights, heavy-duty costumes that seem ill-suited for the sweatbox environment, and loud music. Played out over 15 minutes, these are short-story-sweatathons complete with emotive narrative arcs, elaborate props, and dialogue. Here, Aufguss themes often have a cinematic bent: homemade costumes of characters from Aladdin, Star Wars, and Forrest Gump all featured. (I even spotted The Shape of Water on the program.) One minute, I watched a reenactment of Adam & Eve; the next, a Polish fairy tale about a melancholy violinist, all while enjoying the benefits of those helicopter towels.

“The classic Aufguss is about relaxation, [but] this one is about entertainment,” Lasse Eriksen, one of the judges for the competition, told me over the phone, a few months before the finals took place. Eriksen is one of 14 sauna professionals (selected from a range of countries, to avoid nationalism) who evaluate the competitors, mostly hailing from around Europe, where the Aufguss tradition originated. “You have to learn to do the classic Aufguss first. I can tell really quickly, if you have someone competing who doesn’t really know the sauna.”

But how do you judge whether someone really knows the sauna? It’s in those classic Aufguss elements: fragrance coordination, heat increase, and towel waving, where different moves have defined names. Ice skating has its axels and toe loops — Aufguss has pizzas (think of the Aufguss Master as a pizzaiolo spinning dough, except it’s a towel), combs (a low, sweeping motion, moving the air towards the guests) and the more advanced double eights (in which the Aufguss Master whirls in front of themself in a figure eight). The Show Aufguss is where the narrative themes, costumes, and storyline come in. “When you’re finished and you have this joy in your heart, you really feel like you’ve experienced something and you want to see it again,” Eriksen told me.

“It’s an art form,” explained Janina Lindner, who works at the Satama spa where the event was being held for the third time, using their specially-constructed, 200-person-capacity sauna. “We think if you need to relax, it’s also about being entertained and getting a new experience. It’s a way to forget about the day-to-day. And it works, our guests like it!”

Creativity is encouraged, but there are set rules about what’s allowed once the lights dim. Wajdi Mighri, a Tunisian sauna professional, constructed an Aufguss based on the life of Mozart, in order to compete for Austria. (Aufguss Masters can play for either their nationality or the country they work in.) Unfortunately, he was stymied by the competition’s regulations long before the finals. “I lit candles, which is banned,” he said over e-mail. “That’s why I'm disqualified. But I will return next year with a new project and a new idea.”

In the sauna steam, the guests at Satama appeared to be having the time of their lives. The enthusiasm was palpable, from expectant guests clutching their towels before entering each event to the avid reddened faces, oohing and aahing during the shows. In the first Aufguss I got into, by the Danish competitor Anders Hage, I spotted plenty of his national white-crossed red insignia along the flesh-filled steps — on neck garlands, on huge flags waved from the back seats amid cheers after a particularly tricky towel maneuver, on felted woolen hats, which many of the participants seemed to be wearing (taken from the Russian “Banya” sauna tradition, which apparently help to alleviate lightheadedness).

One memorable Aufguss I caught was entitled “Radioactive,” and began with the Netherlands’ Dylan Beemer entering the room in a full plastic boiler suit and mask. (You would be surprised by the number of layers the Aufguss Masters manage to wear while storming around the sauna athletically swooshing towels over people’s heads.) I was almost relieved when Beemer unzipped down to his T-shirt, and informed us that we were in a nuclear bunker protected from the apocalyptically radioactive world and unfortunately there was a problem with the water outside. He told us not to worry, though — that he was the technician, and intended to protect the bunker from unforeseen radiation poisoning. As the plot unfolded, and his white towels waved the purified steam towards the crowds, disaster hit. Our technician was forced to exit the sauna/nuclear bunker, sacrificing himself to save us all.

Aufguss after Aufguss, I was struck by the ingenuity of the competitors in making the sauna elements fit into their narratives. My favorite, by those Polish cowboys, was entitled “The Good, The Bad, The Ugly” and saw three Aufguss Masters swinging their towels around their heads mimicking lassos, knees bent as if planted firmly on their steeds. They chucked towels from hand to hand — between left and right, between one Aufguss Master and another, across hot stones, and behind their backs.

The feel-good morals, the cookie-cutter characters — subtlety isn’t the Show Aufguss’s selling point.

Towel waving is like a song in a Broadway musical — a part of the narrative form that could seem incongruous but becomes perfectly acceptable if you know to expect it. Like many musicals, the Aufguss stories all had a certain emotional simplicity — unavoidably so, since the time limitations were rigorously enforced. Jiří Zakovsky, the 2017 world champion from Czech Republic, made this time limitation into a feature for “Until The End,” his 2018 entry. The concept: He’s just busted out of jail, and he’s got just 15 minutes to see his dying mother in hospital before the police will surely catch him. In the denouement, he pulled back a medical screen as a voiceover kicked in, the final moments between our hero and his dying mother. “Until the end,” he intoned, solemnly, as an audible buzz of sympathy arose from the guests.

“It’s hard to compare it to something else,” Lindner told me over a fresh mint tea in the nearby café. (Ribbon gymnastics in a Bikram yoga studio? was my best offer.) Not wanting to be rude, I didn��t mention that the narratives sometimes seemed a little pantomime. The feel-good morals, the cookie-cutter characters — subtlety isn’t the Show Aufguss’s selling point.

In fact all of the most popular Aufgüsse seemed to have a kind of after-school special element to them. “We look for stories that are not only fun but that have a moral,” Jareth Geluk, who came second in the team championship last year, told me. Geluk is also a breakdancer, which came in handy in his 2015 routine, in which he somehow managed to carry out multiple backflips. This year, however, he and his partner Veronica Vonk prepared an X-Files-themed Aufguss: “We wanted to do something different — we know people think we’re a bit crazy, but we always do what we love.”

In the middle of the day, it was still unclear who would win, since the judges’ scores were kept secret until the final. In between shows, I took advantage of the one of the final days of summer, swimming in the outdoor pool and lazing around the lakeside sunloungers. The vibe was chilled out, halfway between a music festival and a meditation retreat. As I waited for my towel to dry, two German women on the loungers by the lake complimented me on my very un-British tolerance for the wanton nudity.

It’s true — there were a lot of nude bodies about, even beyond the panels of the sauna, where the dress code was bathrobe (many with various sauna associations’ logos embroidered on them), flip-flops, and Strictly Nothing Else. It’s the same in most German spas, which call themselves “textile-free,” and make bathing suits verboten. It seems hard-coded into some German notion of freedom and relaxation, that one should be able to kick back, naked, outside the constraints of one’s own home, without judgment.

The naturist (or FKK, standing for Frei Körper Kultur/Free body culture), movement has a strong base in Germany, with roots all the way back to the 18th century, maintaining what many Germans see as a natural right: letting it all hang out. Recently, one of the more popular spas in Berlin, Vabali, made headlines when it banned full nudity in between the saunas at its inner-city complex, in order to make it more tourist-friendly. “A wave of prudery is sweeping over Berlin,” decried the national FKK association.

And so here, everyone was, to be extremely British about it, jolly naked. There were even cameras inside the sauna, which no one seemed in the least bit concerned about, although it was written on the ticket and at the front desk that all filmed material was for private, non-broadcast use.

The divisions between the typically nudity-friendly nations and the more prudish weren’t so obvious to see. All ages were represented: I saw long gray beards, and people who looked young enough to be carded. In the sauna, all were equal. “It’s international,” Lindner, the rep from Satama said. “Since 2012, we’ve been the Aufguss family.”

But even in a family, someone has to win. The Poles ended up sweeping the roost, with five teams in the top 16, taking home the first and second prizes in both team and singles competition. (Sadly, my favorites, the tough-talking Polish cowboys with the lasso-style towels, only made it to fifth.) Last year’s winner, the prison escapee, snuck into third; Mr. Radioactive made it into fourth.

To be fair, he did forget his lines right at the beginning of his show. Visibly frustrated, he shook his head; you could feel his panic turning into disappointment as the seconds stretched on. Surely, the judges would take note, and deduct points. But soon, the crowd rallied together, cheering, clapping, and shouting his name.

I’d started the day feeling unwilling and cynical, cringing at the posed sentimentality, the obviousness of the stories’ morals, the childish excitement fueling the whole thing. A few hours later, this feeling had evaporated, sweated out one steamy molecule at a time. The reddened joyful faces, the appreciative applause at a particularly well-executed “Swiss Swirl,” the “3-2-1- Aufguss!” countdown preceding every show — the people had drawn me into the spectacle, and by the end, I’d finally made it. I was relaxed.