In September of 2001, the buildings burned, filling the bright blue sky with black smoke that could be seen for miles. Locals remember exactly where they were when it happened. When the ash settled, many were left in shock. To some, the razed site had been a symbol of freedom, liberty, and enterprise. To others, it had been a manifestation of vice, turpitude, and lawlessness. Either way, it seemed obvious that such an event would be covered and discussed from coast to coast. As a country, we’d eventually begin to truly examine the costs of an overly broad and ill-defined war.

Then, about a week later, 9/11 happened.

And with that, the five-day standoff at Rainbow Farm was mostly forgotten. The 34-acre campground in rural Michigan had, for several years, proudly and defiantly hosted pro-marijuana festivals. Dead and gone were its owners, Tom Crosslin, 46, and Rolland “Rollie” Rohm, 28, killed by the feds and buried by a national emergency.

So much has changed in the past 17 years. Well, some things, at least.

Doug Leinbach, Rainbow Farm’s former manager, still remembers when Merle Haggard arrived at the property for his headlining gig in the summer of 2000. The country outlaw took one look at the huge marijuana-themed party happening on a back road in Cass County, about three hours from Detroit, and said, “I can’t believe they haven’t killed you boys already.”

To be fair, Rainbow Farm was more than a party. Purchased by Crosslin in 1993, he transformed the overgrown acreage. Leinbach, along with a group of regulars, helped him turn Rainbow Farm from a haphazard campsite to one of the most well-known marijuana gatherings in the country. The festivals they created were legit. “It was a big joint effort. Literally, a joint effort,” Leinbach said, emphasizing a pun that’ll never go out of style. “Those people loved Rainbow Farm dearly.”

It took them a few tries to get it right. “We were writing the book ourselves. We were doing what we had to do with what was at our disposal to do it,” Leinbach said.

On Labor Day of 1995, the farm’s crew held a sort of dry run. A $10 entrance fee got you access to, well, not much. The next year, the event was large enough that the Michigan Militia was hired to provide security. The event kept getting bigger — something Crosslin was always pushing for, Leinbach said. The crew erected a full stage, and a general store with a fully functioning cafe and game room. There were working showers. They spent $100,000 building a well. The land was tended to. Crosslin spared no expense. It had come to represent a lot to him.

Rainbow Farm would eventually be known for two events: Hemp Aid on Memorial Day weekend and Roach Roast on Labor Day weekend. In 1999, High Times magazine named the farm No. 14 on its list of the “25 Top Stoner Travel Spots in the world,” nestled between Palau and Nepal. At its peak, more than 2,000 people attended the farm’s events, not including a couple hundred crew members and volunteers. Vendor Row was filled with food and merch. There were speeches, voter drives, music, and plenty of grass. Janis Joplin’s band, Big Brother and the Holding Company, played a set one year. Tommy Chong, working the weed circuit as a cannabis figurehead, was the Hemp Aid ‘99 headliner; the next year, it was Mighty Merle.

The farm was also, for the most part, a family-friendly environment. This was doubly true when festivals weren’t going on.

“There was a real good community on the farm,” Leinbach explained to me as we sat in his garage this past August, about 20 miles from where the farm had burned. I tried to imagine what he looked like back then. It wasn’t hard — with his white beard and ponytail, Leinbach was one part good-ol-boy, one part hippie; a northern Willie Nelson. He continued: “It was family life.”

In today’s lingo, a chosen family. At the core was Crosslin, his partner Rollie Rohm, and Rohm’s young son, Robert. Beyond that, the network of kin included friends like Leinbach, or Crosslin’s 19-year-old nephew Boss.

Crosslin and Rohm made for a perfect odd couple, a complementary pair. Built like a bear, Crosslin was the physical and temperamental opposite of his younger, quieter, partner. He’d get riled up. Nobody who knew him would deny that. As Leinbach put it, “any time I told Tom, or any time anybody told Tom, ‘you can’t do that,’ well, ‘you watch! Don’t tell me I can’t.’ That was the magic words: you can’t.” Although his efforts were perfectly legal, Crosslin had to be talked down from some of his more antagonistic plans, like putting up a sign in near town featuring a giant pot leaf just to piss off the right people.

“Tom was all talk and not much action,” said Don France, Crosslin’s civil lawyer. “He might threaten someone but that’d be the end of it.”

“He was a hothead,” said LaRena Cox, a Rainbow Farm neighbor. Ditto, said Boss Crosslin, Tom’s nephew. “Tom was something,” said another person, deadpan, as they shuffled down the carpeted hallway of a local office to retrieve some paperwork I’d requested.

He was a real character. In other words, Pure Michigan.

The state’s history is a fascinating nexus of radical ideas, like some concentrated resin of our melting pot. Perhaps it’s Michigan’s strange mix of urban manufacturing, rural agriculture, and university culture. The Port Huron Statement, a postwar generation’s rather ambitious manifesto for radical participatory democracy, was issued there in 1962. In 1968, Leinbach’s personal hero, the poet/pot activist/cause celebre John Sinclair, co-founded the anti-racist White Panther Party in Ann Arbor, which itself would become the first U.S. city to decriminalize pot in 1972.

Detroit, of course, was once a working-class boom town. Just across the Indiana state line, Elkhart County still manufacturers and delivers 80 percent of the country’s RVs. As for epistemic virtues, and closer to Rainbow Farm, it was Quakers — the original anti-war protestors — who helped settle Cass County and are still there today. Vandalia, the village in which Rainbow Farm is located, has recently begun touting itself as an important stop on the Underground Railroad, particularly the Bonine House, the dilapidated mansion that Crosslin had purchased and was revitalizing when he died.

But maybe it was simply pot that caused Michigan to really crack up. During the 80-odd years of a confounding national war on weed, in which even hemp was considered a subversive threat, there were fields of the stuff in Michigan. It was as if local farmers had been actively encouraged by a federal government to grow hemp during a World War. Because, well, farmers had been actively encouraged to do just that. It still grows wild in the Cass County area today, nature’s own practical joke.

The point is: Crosslin, like the state itself, had a hard-scrabble, contradictory, and often anti-establishment streak.

“He was a Barry Goldwater conservative,” Leinbach said of his friend, who three times voted for Republican presidents. Crosslin’s politics, if they could be boiled down to anything, resemble that of a classic liberal: Private property, individual rights, and the freedom to run a giant weed-themed festival without tyranny. Absolute ideas taken to a logical yet radical conclusion.

Born in Elkhart, Indiana, Crosslin had done a lot of things in his life before settling in Vandalia. He was in a biker gang. He brought a gun to a paycheck fight — he’d been stiffed by the employer — and was convicted of felony. Later, he was a long-haul trucker and moved to Oklahoma for a stint where he made good money selling pills (legal ones) in Tulsa along with buying up land contracts and becoming proficient in steeplejacking, namely by building flagpoles. He was a blue-collar entrepreneur. At one point he was even married.

Once he moved to southwestern Michigan in the early 1980s, Crosslin began buying old homes, fixing them up, selling them. In between all his small-time hustles, he met Rollie Rohm.

Crosslin, like the state of Michigan itself, had a hard-scrabble, contradictory, and often anti-establishment streak.

Rohm, according to just about everyone I talked to, was “really easy going” and “very peaceful.” He was “the quintessential hippie” without “a mean bone in his body.” Working at an RV factory, Rohm was living in Elkhart, Indiana, and, at 16, already separated from the wife with whom he’d had a child the year before.

Sometime in 1991 or 1992, Rohm moved into a group house that Crosslin owned. Later, they’d move together to a more private residence, and then to Rainbow Farm. Once they became a couple, they also became a family; Crosslin treated little Robert as his own, and by 1994 Rohm had full custody of his son. The family didn’t “flaunt” what they were, as one big ol’ boy in overalls put it to me (he meant well). But they weren’t ashamed and didn’t hide it either. “You knew one came with the other,” Cox said. “If someone asked,” Leinbach said, “Tom would tell ’em.”

Beyond their immediate family, the network of kin included a few close friends and family members like Leinbach and Boss Crosslin. Neighbors, too. Even if they were squares.

“Going on record, I do not smoke marijuana, I just don’t,” said Cox, whose family has lived right down the road from Rainbow Farm since before Crosslin and Rohm ever moved in. “But a lot of people in the area do and it was a place they felt safe.”

She still misses them. “They were just excellent neighbors. They were wonderful,” she said. In the fall there were hayrides. In winter, if Cox’s driveway got snowed over, it always got plowed. This cultivated a deep sense of belonging. “I appreciated feeling like somebody had our back,” she said. Those working at the farm who didn’t know her name referred to her as “that lady who sends cookies and pies and brownies.” She and her family felt perfectly fine visiting the annual festivals during the day (at night there was a “hippie slide,” clothing optional).

As those who knew him will eagerly tell, Crosslin’s generosity extended beyond Rainbow Farm and his immediate neighbors. Cox told the story of the time when Crosslin, upon discovering kids at Robert’s school didn’t have enough money for lunch, donated enough so every student could eat that year. He offered the same support for needy families during the holidays, and folks who just needed a little extra help.

Life around Rainbow Farm was about as generous and idealistic as you could get. “He just wanted to live his life and not bother other people,” Cox said. “He felt that what was true and fair was that families should not have to have a father absent or a mother absent because they smoked marijuana.”

For Crosslin, Rainbow Farm was a place where all the freaks of Michigan and beyond could gather. With weed advocacy and the people it attracted, he found meaning and compatibility in a movement that was just at the brink of becoming mainstream, of causing real change.

Unfortunately, what Rainbow Farm stood for was in direct opposition not only to conventional standards but to the established rule of law.

In 2001, as during festivals past, police put up barricades to the road that fed Rainbow Farm’s main gravel access before the Labor Day festivities began. This time, however, they also surrounded the 34-acre property. By that Saturday, helicopters and light armored vehicles were brought in.

The standoff lasted all weekend. Crosslin would die that Monday, Sept. 3. Cox remembers what happened next vividly. “It was very early the following morning, and as I’m taking trash out to the dumpster, I have a police officer running at me, telling me ‘you need to get back in your house right now!’” she said. “And I remember absolutely losing it and saying, ‘well why do I need to go back in my house right now, you’ve already shot my neighbor, what more can you do?’

“And at the time that I said that ... there were gunshots fired.”

It was the tragic coda to Crosslin’s protracted battle with local officials over Rainbow Farm.

Not too many people ever have an archenemy, but Crosslin did — Scott Teter, the Cass County prosecutor. Crosslin’s battle with Teter began almost immediately after the latter man was elected in 1996. In the position until 2008, Teter would later run for two different judgeships. More than one person I spoke with slyly noted that he lost both times. During those campaigns, “Remember Rainbow Farm” had apparently been a not-infrequent refrain from unhappy locals.

Teter was notorious for his tough-on-crime approach.

As county prosecutor, he first earned brief national attention in 1997, and an appearance on the Today show, for putting up four billboards in Cass that read “If your sex partner is under 16, they won’t be when you get out of prison.”

One person I spoke with said that Teter was a “religious zealot.” Others in the area, who never wanted to be identified, described Teter as uptight or, uncharitably, as a “fundamentalist guy.” Whatever the case, Teter was fair but firm. “You usually heard about the cases where I put the hammer to somebody, which I will do. There are times that’s completely appropriate, and I don’t apologize for that a bit,” Teter told Leader Publications during his 2008 campaign. “But other times I sat down with the defendant and the defense attorney to talk to them and find out who this person is.”

“They were two sides of the same coin,” said Boss Crosslin, who spent his formative late-teen and early twenties years on Rainbow Farm, of Teter and his uncle. “They were both passionate about their beliefs.”

It was one of the more diplomatic descriptions I’d hear of Teter (he did not respond to requests for comment from The Outline). Another came from Robert Rohm, Rollie’s son. The younger Rohm gave his only on-the-record interview to date in July, after it was announced that environmental journalist Dean Kupiers’s 2010 book, Burning Rainbow Farm: How a Stoner Utopia Went Up in Smoke had been optioned for a movie. (In trying to contact Robert myself, I was told he had my number and would call if he wanted. Several former longtime employees of Rainbow Farm either declined to respond to interview requests or told me to get lost.) “At the very end of the day,” Robert said during the TV segment, “my dad and Tom could have made a different choice. And at the same time, the police could have made a different choice."

Rainbow Farm’s pro-weed protest celebrations and its family of outsiders were the antithesis of Teter’s conservative, law-and-order agenda. But the problem for Teter was that the potheads were doing everything by the book.

In 1997, the county filed for an injunction against Crosslin, claiming he had “violated the Cass County ordinance relating to gatherings of people in excess of 500.” He beat that by obtaining non-profit, 501(c)(3) status. The county again tried to put a stop to the farm’s events in 1998. A year after that, the county claimed the organization had actually lost its designation and that “Mr. Crosslin is required to go through the licensing application process,” if he didn’t want to be sued. Again. It was a clerical error that was quickly corrected. The festival was back on. Again.

Rainbow Farm’s pro-weed protest celebrations and its family of outsiders were the antithesis of Teter’s conservative, law-and-order agenda.

Other salvos were more visceral. During the festivals, law enforcement set up roadblocks to intercept incoming and outgoing attendees. “[Rainbow Farm]’ was as safe as could be,” Boss said. “But as soon as you got off the property … you just had an uneasy feeling because there were so many police officers.” A lot of people from nearby Elkhart, Leinbach said, were worried about authorities recording their license plates. We’d love to come to the festival but we can’t. We’re scared.

Those who spoke to me, most notably the non-smokers, said Crosslin policed the festivals heavily for the bad stuff. “They were extremely anti-any other drug,” Cox said. Crosslin’s civil lawyer, France, who himself has never partaken, echoed this claim. Leinbach said Crosslin wasted no time throwing anyone out whom he caught selling narcotics.

At least a small amount of this had to be out of vigilance. Getting nowhere with the lawsuits, Teter had established a drug task force dedicated to Rainbow Farm. Narcs went in to make buys. They were there during Hemp Aid ‘98. They found some acid here, some coke and pills there, but nothing substantial enough to indicate anything organized, certainly never anything that implicated Crosslin was any kind of kingpin.

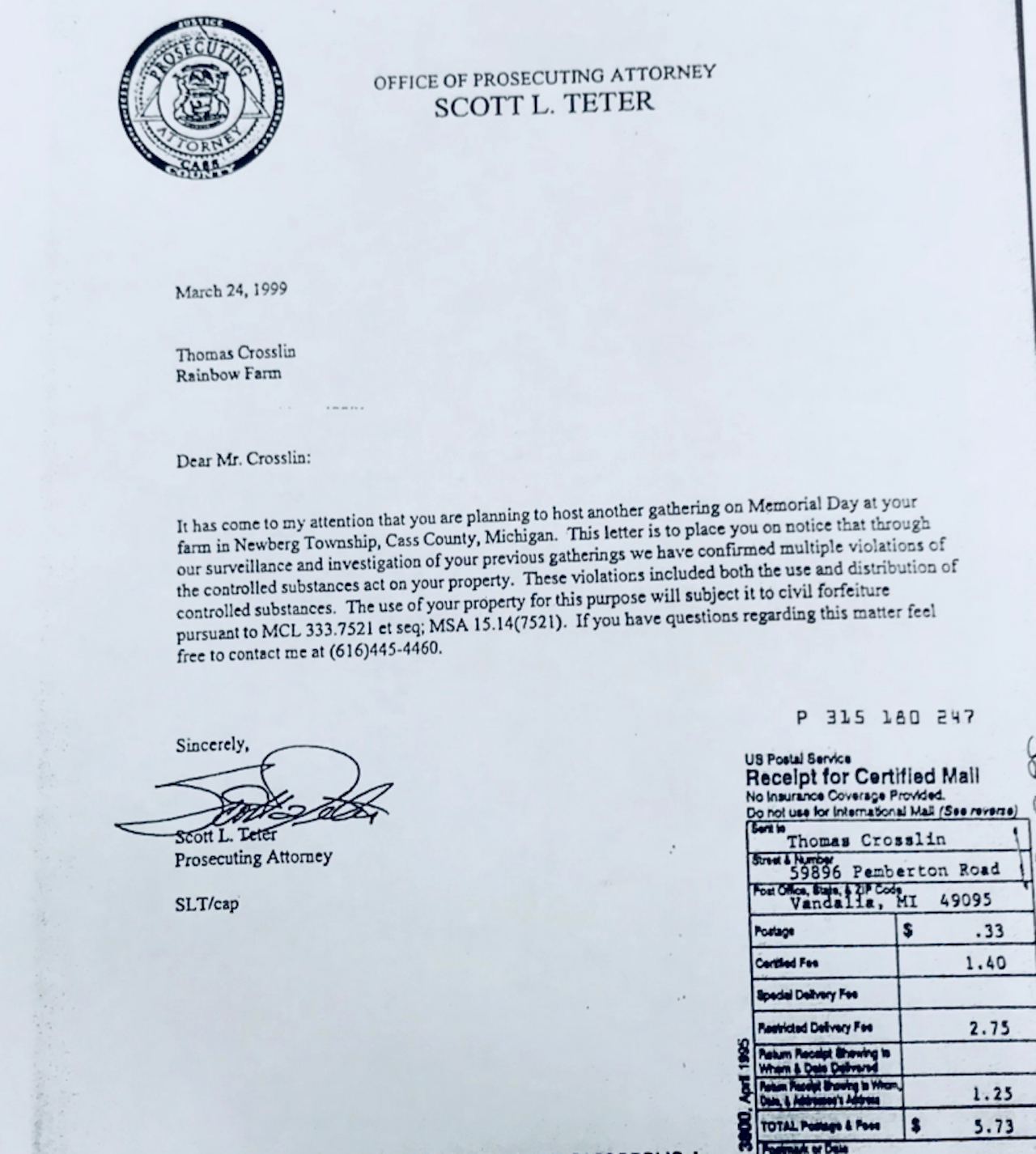

Still, in March of 1999, Teter sent Crosslin a letter informing him that thanks to "surveillance and investigation,” there was evidence that hard drugs were being distributed at Rainbow Farm; and if he could prove a connection with Crosslin or any of the vendors, the use of the property for such a purpose would make it “subject to civil forfeiture.”

By then, Teter had been looking for any way to snuff out Rainbow Farm. He was just doing his job, after all. The law’s the law. “I’m on one side and I’m going to enforce the law that he does not agree with and is violating. That puts us head-to-head. Unfortunately, there’s not a lot of other ways around that,” Teter told author Kuipers. “I understand that he [Crosslin] did some positive things with the community. It has nothing to do with whether they were good people, bad people, or whatever. They made bad decisions. I took an oath to do something about it.”

Crosslin had a similar, if oppositional, sense of duty. He wasn’t going to back down. After the county’s efforts in 1997, he wrote a letter to the county administrator that was polite and diplomatic. In 1998, after a similar effort to stop the Rainbow Farm festivities, he sent Teter a strongly worded missive declaring his Constitutional right to peaceably assemble, and reminding the prosecutor of the government’s obligation to protect the freedom of its people. “And now you write a letter threatening me with warrants for my actions on behalf of freedom on this property,” he wrote. “You need to watch what you wish for, because these rallies are going to continue.”

It was in response to Teter’s letter the following year that Tom showed just how angry he was with the constant attacks: “We are all prepared to die on this land before we allow it to be stolen from us. How should we prepare to die? Are you planning to burn us out like they did in Waco, or will you have snipers shoot us through our windows like the Weavers at Ruby Ridge?”

Some context: along with compact discs and the national obsession with the president’s sex drive, America in the 1990s was notable for a wave of anti-government resentment and bloodshed. That wave crested with Rainbow Farm. Even before the militia had provided security for the festivals, Crosslin had already incorporated some hyper-individualist views; he was not entirely unsympathetic to the core message of their most egregious actors.

In 1992, the 11-day standoff between a fundamentalist, anti-government family and federal agents at Ruby Ridge in Idaho had left a 42-year-old mother, her 14-year-old son, and a U.S. marshal dead. In 1993, 75 people died during the highly televised 51-day siege between the government and a religious sect in Waco, Texas, lead by a man named David Koresh. The original Michigan Militia formed in 1994 to combat what it perceived as a government that increasingly and tyrannically snuffed out the inalienable rights of sovereign citizens.

The following year, two anti-government extremists named Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols would carry out the country’s largest and most fatal domestic terrorist attack, partially in response to incidents like Ruby Ridge and Waco. Crosslin was at a local bar watching the Oklahoma City Bombing unfold when he got into a brawl that put a woman in the hospital. Versions of what happened vary, but not the part when Crosslin repeatedly yelled “Fuck the government! Long Live David Koresh!”

A little off-grid with a survivalists’ can-do attitude himself, Crosslin was viscerally aware of what radical anti-government folks might decry as “creeping authoritarianism.” Somebody like David Koresh had serious issues, but events like Ruby Ridge and Waco were — and still are to many — another example of excessive government reaction pushing a non-traditionalist to extreme measures.

Crosslin thought the government was after him as well, which sounds paranoid if it weren’t true. It should be no surprise then that the militia-minded crossed paths with some of the more out-there marijuana advocates of the day. And while the Michigan Militia, an iteration of which gets a little limelight every couple of years, served as security for two of the festivals, their hyper-tactical vigilance — while used and appreciated — tended to be a buzzkill to the many peaceniks in attendance, Crosslin included. Plus, they had wanted to arm themselves, a request that was denied. Leinbach said they were still welcome, and many returned as paying customers.

Whatever originally inspired Crosslin, it was the government, the powers that be, that became his primary enemy. And the enemy was coming at him from all sides. In that 1999 letter referencing the deadly standoffs, Crosslin made clear his position: “If you choose to send out your secret police, I hope you are standing there on the front line to witness the result of your action.” He told Teter that if he continued, “you will have the blood of a government massacre on your hands.”

There would be a reckoning.

“I’ve always thought that 9/11, because of the magnitude of what had happened, it cast such a huge shadow over anything else going on at the time,” Cox said. “Nobody’s going to pay attention to or care about a little farm in Vandalia, Michigan, when all of that was going on in New York.”

With 9/11, the country would turn its attention from domestic radicals to those of the international variety. It was the beginning of a new era of fear; the FBI was no longer an overzealous agency intent on killing non-conformist citizens, but one that had done too little in stopping terrorists from flying American planes into American buildings.

Understandably, the story of Rainbow Farm died on 9/11. But the farm had been in trouble long before that. Ironically enough, the beginning of the end for the farm started that year on 4/20.

Driving down the road in the morning hours after the farm’s April bash, Konrad Hornack,17, ran his car into a school bus full of students. The only fatality, he was found wearing a Rainbow Farm wristband. During a press conference, authorities made it clear who they believed was to blame. Teter finally had the ammunition he needed to strike.

Three weeks later, on May 9, the farm was raided by state police in tactical gear. Not for weed, but for tax reasons. Officially, they were seeking “financial and accounting records from 1998 to present including all payrolls records.” Cox remembers seeing the convoy of unmarked vehicles barreling toward the property to serve the warrant.

Two years before, when Rainbow Farm had been hosting people like Tommy Chong, Teter had developed a confidential informant who’d testify that the festival had not been withholding payroll taxes. Nevermind that the farm had paid all its sales taxes and that the “employees” were part-time seasonal workers with 1099 tax-exempt status. The raid was that pedantic.

But Crosslin had also made a huge error. Inside the main bedroom, authorities found two loaded shotguns, and in the attic, a loaded 9mm in its case. As Kuipers put it in his book, “the guns were ordinary stuff you’d find in any Michigan household that has guns.” But the real problem wasn’t just that Crosslin, with his 20-year-old felony conviction, was barred from owning guns. It was the grow operation authorities found in the basement — at least 200 plants.

Crosslin thought the government was after him as well, which sounds paranoid if it weren’t true.

Even to this day, people like Leinbach will acknowledge that Crosslin and Rohm had made a critical mistake, inviting serious trouble with their illegal, personal-use garden. The couple was arrested. The day after, a court injunction and temporary restraining order were issued, banning any more festivals. Teter followed that up with the biggest hit: an 18-page complaint detailing the soft evidence he’d gathered, culminating with an official request to proceed with a drug asset forfeiture, just as he’d threatened to do in the 1999 letter. He wanted to take the farm. “These people were basically thumbing their noses at Michigan and federal drug laws and the local law enforcement agencies in the area,” said Teter in a press release following the raid.

On May 15, with a petition filed by Teter, 12-year-old Robert was removed from school by a sheriff and placed in the custody of Child Protective Services over concerns of “neglect and abuse.” It was an absurd accusation to many, especially Cox, whose daughter frequently played with Robert. When needed, Crosslin and Rohm would even babysit. “Never ever was there a question of [my daughter’s] safety. They were probably a bit more protective than I am,” she said. For the next three months, Crosslin and Rohm spent what remaining money they had on saving the farm and reuniting their family.

The summer was relatively undramatic until Aug. 17, when Crosslin held a small, haphazard event and shortly thereafter announced on the festival website that Rainbow Farm would hold a Labor Day party. Both were in direct defiance of the restraining order. The next week, Teter informed Crosslin and Rohm that they would be required to appear on the last day of August for a bond revocation hearing.

By the morning of Aug. 31, Tom had started informing the few campers on the farm that they needed to leave. He also went around to neighbors like Cox, telling them “something’s going to go down.” He offered to pay for her family to stay in a hotel room. By the time Cox went down to the farm to check on Crosslin, the smoke had already begun to rise. Tom had set fire to several structures, including the general store, supply building, and ticket booth. It was the day of his bond revocation hearing.

It was past noon that day when a local TV helicopter swooped down for an aerial shot of the developing story. That’s when Crosslin, believing the chopper was the police, took several potshots with a firearm acquired after the May raid. The helicopter took a few hits and retreated. It was around this time that a neighbor’s relative called 911, relaying what Crosslin had made abundantly clear: he wasn’t going to let Teter take his property, and he had armed himself to protect it.

Law enforcement began arriving on the scene, posting up more than three-quarters of a mile away just off the main highway road. More than 100 local and Michigan state police, as well as FBI arrived on the scene. There were at least two SWAT teams, helicopters, and a couple tank-like tools called lght-armored vehicles (LAVs). The only structure that remained was the farmhouse near the entrance, where Crosslin and Rohm were holed up. Authorities kept their distance. More than a decade of ugly, high-profile standoffs had the FBI weary of any drastic action.

By that Sunday, Sept. 1, a couple friends had managed to sneak in and out of the perimeter. One acquaintance had been with Crosslin and Rohm when the fires began simple strolled off the property. Another managed to get onto the property without detection and remained there until Crosslin was killed. Yet another farm friend was sent several times by officials looking to end the situation without incident. He brought McDonald’s. It didn’t work. Nothing did. Authorities had even sent in Crosslin’s parents, who shared a beer with their son but were otherwise unable to alter his position.

More than a decade of ugly, high-profile standoffs had the FBI weary of any drastic action at Rainbow Farm.

News of the situation had begun to spread. National media outlets like CNN were taking note; a camp of protestors established themselves right off the main highway.

On Sept. 2, state troopers attempted to bring the entrenched couple a cell phone, arriving at the last remaining farmhouse in a LAV only to be fired upon multiple times. That evening, FBI agents were dispatched to three positions surrounding the property. They settled in with snipers in hand.

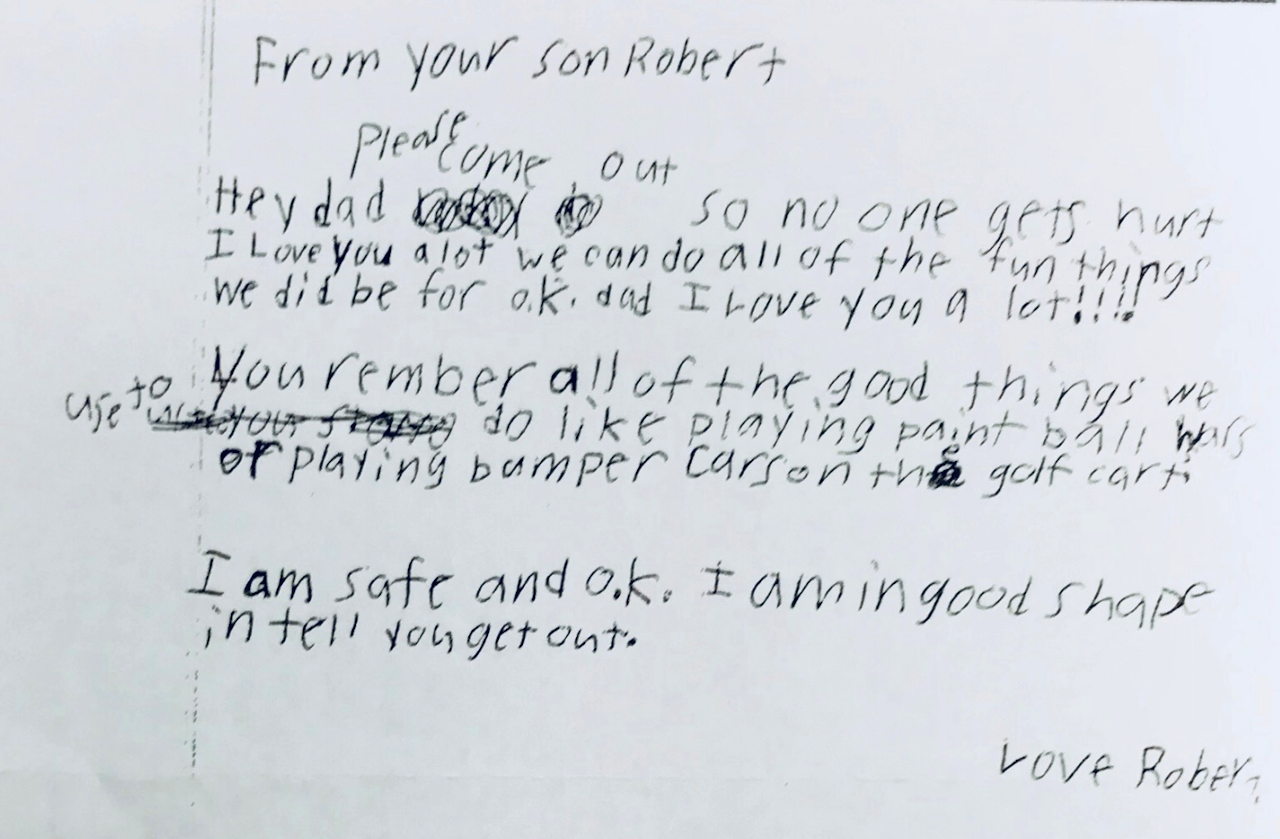

Sept. 3 and no significant developments. By then, a new phone line replaced the one that had burned during the fires. The FBI located Robert and had him write a letter. It began: “Hey dad please come out so no one gets hurt.” In was in the late afternoon that Crosslin took a short trek to a neighbor’s abandoned house for a few supplies. He was returning to the farmhouse, rifle in hand, when he stopped near a tree line. He took a few steps toward it and raised his gun when an FBI sniper hiding in the detritus shot him. He died instantly, his skull ripped apart by a .308 slug.

It wasn’t long after that the FBI snipers retreated and turned over control of the standoff to Michigan State Police. According to Kupiers in his book, it was around 3 a.m. the following morning when Michigan State Police, with their LAV sitting in front of the house, fired a few 12-gauge rounds from beanbag gun and another few “baton” rounds through the windows and doors in order to “wake [Rohm] up.”

On the phone with negotiators, Rohm, now entirely alone, agreed to surrender if he could see his son. A 7 a.m. surrender was set. But at 6 a.m., police reported that the upper level of the house was on fire. It wasn’t for another 30 minutes, as the flames spread, that Rohm burst out of the house. According to the official reports, Rohm, raised a gun on officers in the LAV, and was shot multiple times by snipers.

The standoff at Rainbow Farm lasted five days. Rohm would later be buried just a few hours after the towers fell.

Before 9/11, 12 states had decriminalized weed to various degrees. By 2001, eight states had legalized the use of medical marijuana. Then, between 2002 and 2012, 10 states passed legislation approving the medicinal use of cannabis. To date, 30 states and Washington D.C. states are legalized for medical purposes, nine for recreational use.

Rainbow Farm had served as a waystation for the rising marijuana movement. In the years leading up to the siege, not only had there been a line of speakers and pro-marijuana advocates ready to take the campground stage, there’d been a concerted effort to enact real reforms.

“Some of the biggest marijuana advocates in the state of Michigan … they cut their teeth at Rainbow Farm,” Leinbach said. “It goes back to the PRA, the Personal Responsibility Amendment.”

The PRA was a state ballot initiative for 2000 that would have essentially legalized very small amounts of marijuana for personal use within private dwellings. Rainbow Farm went full bore. During the 1999 festivities, so many voter registration forms were distributed that the local clerk's office ran out and incoming festival attendees were encouraged to stop by their local municipality for more.

“That’s when we brought people in who taught people how to organize … how to register voters, how to stand outside of fucking Walmart and get signatures,” Leinbach said.

It wasn’t just a stoner-drive either. Even Cox canvassed, despite the fact that she’s “not the biggest fan” of lazy potheads who — she said with a naughty giggle — “need to get their shit together.” The mother of two had several reason for passing around the petition, particularly to others like her with professional careers. For starters, a lot of her fellow nurses working in hospice care saw the benefits. But the biggest reason was personal.

“I did that was because my husband smoked marijuana [from] the day I met him [until] the day he died [in 2007].” In all of the time they were married, her husband missed three days of work. “It was so taboo” that if Cox’s husband had ever been pulled over, or if the police had found anything when the family once had called to report a robbery, “this great, tax-paying, law-abiding citizen except for this one thing” could’ve gone to jail. “And so for me, it was very important that this bill could pass.”

Sure, Cox said, “a lot of people questioned [her canvassing],” including the fellow church members she pushed it on. The PRA failed but efforts like hers, over time, seemed to have an affect. “It opened up a dialogue,” she said.

“It’s almost like you’re coming out of the closet and I think that the people like me that don’t use it are [now] more supportive of it because we know someone who does, and we love that person, and we don’t want them to face the legalities of minor possession,” Cox told me.

In 2008, residents did more than talk. Michigan pot proponents outmaneuvered its many opponents in the legislature and prevented politicians from gutting any proposed medical marijuana bills by simply pushing for a full ballot initiative. The law established legitimacy for some licensing, cultivation and use, including the creation of “caregivers” who can have up to five patients and 72 plants.

When the 2008 initiative passed, Cox was shocked. Not by the initiative, but the people who voted for it — one in particular. Her husband’s mother, “a retired conservative school teacher, member of every committee known to man, active in the church — she saw a benefit for it, and she voted yes for it,” she said.

Getting grandma on board is huge. And while the green revolution may now seem even more inevitable — especially in liberal paradises like the coasts and urban centers— it’s in rural and traditionally more conservative areas where a total win is an uncertain prospect.

Four states maintain hardline stances and won’t allow even a whiff of cannabis. Sixteen states, most of them in the South, only allow snakeoil (aka CBD). It’s true that Oklahoma just passed a major medical marijuana initiative. But the state is still suspicious of its brand new climate. If Michigan is any indication, Okies should prepare for an adjustment period.

It was another eight years before Michigan passed a trio of 2016 bills that allowed for larger grow facilities to operate. Yet the state has dragged its feet on implementing a coherent system. In December of last year, the Detroit Free Press reported that only 41 communities have voted to participate in the law, while “many communities in the state — 85 outside of metro Detroit — have decided to prohibit medical marijuana in their towns.” Cass County was one of the many that took a hard pass. It’s a decision that agrees with Scott Teter’s successor, Victor Fitz, an outspoken opponent of the law and marijuana issues in general.

“There’s ample opportunity for someone to get medical marijuana if they want it. But we don’t want to have that industry in our backyard,” said Fitz, considerate and straightforward during our phone interview. “There’s some negatives to that that are certainly well-documented and legitimate.”

“Some of the biggest marijuana advocates in the state of Michigan … they cut their teeth at Rainbow Farm.”

Previously a narcotics prosecutor, Fitz patiently gave me a number of reasons that Cass County doesn’t want to be involved in any pro-marijuana efforts. Fitz said that according to the Michigan medical community, the medicinal uses are an “overstated proposition” with “maybe some real limited application” (the list of profound benefits that such a miracle drug provides is a little hard to smoke). He mentioned, too, cases of abuse: express-lane “marijuana mills” where “you say a couple of magic words and you get the card.”

Other frightening prospects have been touted for years now. “It’s not the 1970s marijuana, it’s much more potent,” he said. Fitz also cited the much-debated Dunedin Study, which found heavy marijuana use between the ages of 13 to 38 significantly lowered IQ points.

Plainly obvious even to casual observers — and something that marijuana opponents like Fitz undoubtedly understand — is that relaxing laws, even for medicinal reasons, is a slippery slope, depending on how you prefer to slide.

“What I see a lot of in Michigan, is that ‘hey it’s time for us to be the adults in the room,’” Fitz said of calls for legal recreational use. “Certainly there’s some sympathy for medical marijuana but when it comes to protecting our child, and what we want our state to look like, we prefer it the way it is.”

Whatever marijuana moment is happening nationally and in the mainstream, the cognitive, cultural, and legal dissonance in rural-based areas like southwestern Michigan is jarring.

Indiana has never passed any pro-marijuana legislation and their law enforcement does not play around. “For our perspective, the way Indiana law works — if you have marijuana in your system you are committing a crime,” one border county deputy prosecutor was quoted as saying in February. He said the state line was “basically the drug equivalent to the Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” perhaps unaware that he was favorably comparing authorities to a murderous demon with no head.

The legal changes can be nightmare for the decade-old civil liberty in Michigan, too. Earlier in August, about three hours north of Vandalia, an 80-year-old arthritic great-grandmother was arrested and spent a night in jail because her marijuana card was expired.

In Cass County, Fitz is very clear that his office adheres to the law. The “simple policy” regarding marijuana cases, is “if you’re operating within the law, we’re going to leave you alone. But if you’re breaking the law, we’re going to criminally prosecute you.”

For whatever reason, some Cass County residents operating within the law didn’t want to speak with me. Perhaps it was related to Cox’s description of Vandalia as “a very tight knit community ... a very small town.” It’s a place, she said, where “if I farted today, I promise tomorrow morning, the people down the road would know how bad it smelled.”

When I first arrived in Cass County, the place smelled great. August in southwestern Michigan is a lush paradise. Where there aren’t ponds, marshes, or lakes, the landscape rolls smooth and gentle. Backroads have canopies, and where the wild has been tamed, it’s been cultivated. There’s farmland everywhere, mostly soybeans and corn — actual waves of grain.

In Vandalia, just a few miles from Rainbow Farm, there’s a non-profit foundation. A marquee right by the entrance declares that it is “Championing the Entrepreneurial Spirit.” The foundation is named after the area’s other hometown success story, Edward Lowe. Edward Lowe invented kitty litter.

Rainbow Farm doesn’t have so much as a marker, even though Crosslin had always championed the entrepreneurial spirit. Hippie as it may have been, Rainbow Farm had spurred growth and economy. Although it represented a family and was an active, defiant part of the ever-growing marijuana movement, Crosslin also saw Rainbow Farm as a business. According to Leinbach, his friend invested at least $750,000 into operations. The money made from his rentals, sometimes by selling off property, he’d use to cultivate. He built it, and they came.

“The festivals brought in people, it helped the local economy,” Leinbach said. From the attendees making purchases at nearby markets and gas stations, to the local suppliers of ice, firewood, straw, or services like medics and porta potties, Leinbach said “the money we circulated into the community every [festival] weekend was easily half a million dollars.” Crosslin was a job creator. “He would hire people that were typically, traditionally not hirable,” Cox said. “People that would look at them and you would say ‘hell, I don’t want that guy working for me, he looks like a bum.’ And in turn, we started to treat them differently.”

A lot of the income went to fighting the costly drug war. “We paid $25,000 for every show to fight the charges that Teter filed against us,” Leinbach said. “We lost a thousand, maybe more, customers every show because they turned around at the roadblocks.” Unlike kitty litter, America just wasn’t ready for what Rainbow Farm was offering.

“There were ahead of their time. Had they had the stance that they had then, maybe even three years ago, I don’t think what happened would have happened,” Cox told me. “They were rocking the boat. They were basically thumbs-up to the powers that be.”

It was nephew Boss Crosslin, now 38, who finally facilitated a visit through to the farm during my last few hours in Michigan. The younger Crosslin, being on neighborly terms with a few of the current owners, was a welcoming guide. He’d been entrusted with his own gate key. Boss — his given name as was it his grandfather’s — was eager to keep the legacy of Rainbow Farm alive.

Just past the farm’s main gate, we tramped up a hill. At the crest, Boss and I wiped sweat and slapped bugs as we stood on the spot where Crosslin had died. Boss aimed at the underbrush just a few yards ahead of us where the FBI sniper who killed Crosslin had been hiding. It was a little obscured by distance and leafage, but from our vantage point we could just about see down the hill to where Rohm had died the next morning. His limp arms had been handcuffed as one of the last buildings on Rainbow Farm burned to the ground.

Still standing today, though just barely, is the main stage. It’s ripped up and rotting. Down below, the land undulates for several acres. The festival’s main field has long since been turned into industrial farmland. Soybeans. Elsewhere on the ghost tour, Boss and I would see old fire pits, or overgrown trails and golf cart tracks. Boss knows every bend, dip, and ridge of the land. He pointed out all the spots where, come spring, he will again spend his free time foraging for sackfuls of wild mushrooms. But things could change, and soon.

On Michigan’s November ballot is an initiative that would allow recreational weed. A representative with the state chapter of the National Organization to Reform Marijuana Laws said polls have them feeling “cautiously optimistic.” Prosecutor Fitz has apparently seen other figures and is cautiously optimistic about the ballot’s failure. The states that have taken such radical departures from traditional drug policy, he said, are “on either the east or the west coast, and Colorado.” In “the Midwest, the breadbasket of the nation so to speak, there is no recreational marijuana.”

But among the core, all-American values, especially in the heartland, opportunity and enterprise are premium. Weed fits nicely into this value set.

“We have a farmer in the area, his family’s been farming here for 80 years ...,” Cox said. At a graduation party, this farmer — “they don’t smoke marijuana at all” — told Cox that they were thinking about qualifying as medicinal caregivers. “And I said, ‘wow, that’s a huge thing to say.’ And they said, ‘yes, but it’s legal and we’re able to sell this ... and it’s a profit. We’re farmers, so obviously we know how to grow stuff.’”

Even small-town farmers know that green is green. The billions of dollars in revenue being generated in pot-friendly states is already well established, as are the hundreds of millions each state collects from related taxes and fees. Outlaws and rebels, too, are cashing in. Tommy Chong has long been peddling weed-related products. Stars like Willie Nelson and Snoop Dogg have leased their personal brand. So why wouldn’t that work for something more downhome? Something from Middle America? Something that’s Pure Michigan?

For some time now, Boss Crosslin has been wondering about that very idea. Currently, he builds RVs in Elkhart, like Rohm did, and has two children whom he’d like to truly provide for. He wants to find a way to work smarter not hard, he said. Like his uncle, Boss is an ambitious man with radical ideas. He’s drawing up business plans, negotiating with neighbors, and talking to interested parties. He’s cultivating all the possible marketing options and product opportunities, working to make sure everything’s in a row before he plows ahead. It’s just a matter time before the laws rotate.

“I’m trying to do everything legal and by the book because I feel like the best thing I could do would be to set up a grow operation on Rainbow Farm,” he said.

That, Boss said, “would be the biggest slap in the face to the government here. That would be Tom kicking them in the fucking nuts.”