Zac Clark, a 26-year-old photojournalist and filmmaker from Michigan, voted in his first election — the 2010 midterms — when he was 18. He voted again two years later in the 2012 presidential election but, since then, he hasn’t voted as consistently as he’d like. Between moving around a lot, not having access to a vehicle, and not knowing where to register, his engagement lapsed. “You get a ticket for not moving your license or doing anything like that. There’s monetary consequences for you not doing these things,” Clark said. But there were no prompts, reminders, or penalties for failing to register to vote.

However, when his 93-year-old grandmother was hospitalized and his family told him how much the medical bills were, something crystallized for him. “They’re talking about the bills, and the bills in numbers-wise are eerily close to the number of my student debt, and I’m just watching my family boil ourselves down to these numbers and… I’m not hearing progress, I’m hearing literally surviving,” said Clark. Where generations past had been able to pass on resources to younger family members, that’s no longer happening. He felt that if more candidates focused on issues that working class Americans face, it’s possible that more young people, like himself, would be compelled to turn out to vote.

Midterm elections aren’t usually high-turnout affairs, especially for Millennials. But the November 2018 midterms are being called the most important election in a lifetime. The outcomes of these races will determine which party controls intelligence committees, who will influence health care and immigration, and may even determine the likelihood of an impeachment. According to Pew Research, in 2014, the most recent midterm, Gen Xers and Millennials — nearly 60 percent of whom align with the Democratic party — cast 21 million fewer votes than Baby Boomers and older generations. And, as 2016 taught us, those missing votes matter.

This urgency has spurred organizations like Justice Democrats, a federal political action committee, to encourage more candidates to run on the kinds of progressive platforms that resonate with young voters. Its candidates pledge not to take any corporate-PAC or corporate-lobbyist money and are running on the Justice Democrats platform, which includes things like single-payer health care, tuition-free college, and abolishing Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Some of their more high-profile candidates include Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who is running for congress in New York; Rashida Tlaib, who is running for congress in Michigan; and Cynthia Nixon, who is running for governor in New York.

Getting candidates to speak to issues that matter to Millennials is only half the battle, though. In addition to convincing young people that their votes matter, they also need to be registered. An organization called HeadCount, which formed in response to the Iraq war, reports of abuse and torture at Guantanamo Bay, and the aftermath of the 2000 presidential election, has been registering young voters since 2004. Marc Brownstein, one of HeadCount’s founders, noticed that after the 2000 election his band the Disco Biscuits played shows for more crowds that were larger than the difference between George Bush’s and Al Gore’s votes. Brownstein thought about the tremendous audience that musicians have, and the capacity that they had to inspire and to influence society, which spurred him to launch the organization with his co-founder, Andy Bernstein.

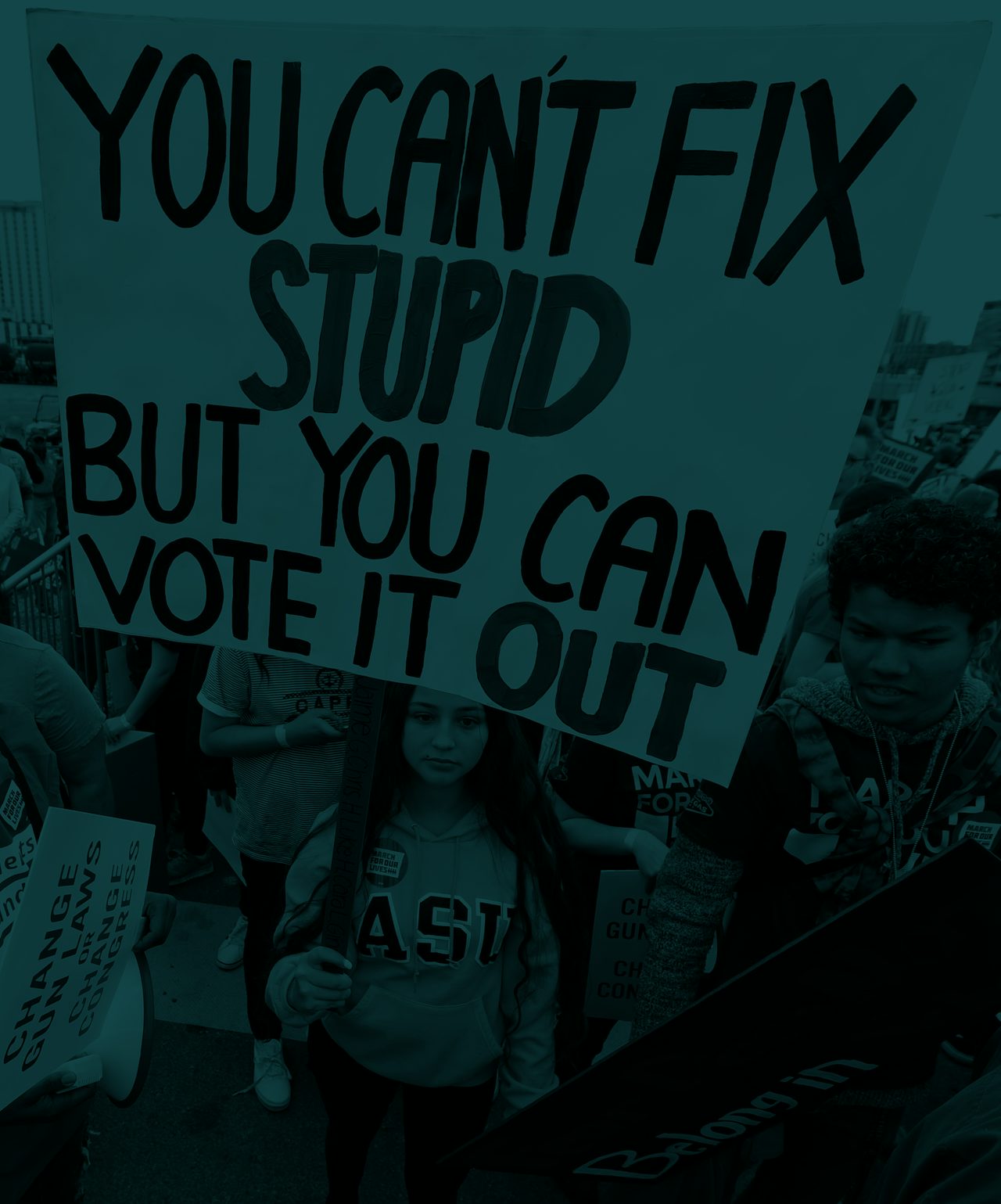

HeadCount is not the first or only organization that is targeting young voters. Rock the Vote has been targeting young people since 1990, using music and pop culture to connect with young people. The Campus Vote Project and Campus Election Engagement Project were formed in 2012 and 2008, respectively, and target college students. And more recently, March For Our Lives, which rallies for stricter gun-control laws, partnered with Headcount to register students at high schools.

HeadCount sends reps to concerts and music festivals to register younger voters. It was at Electric Forest, a music festival held in Rothbury, Michigan earlier this year, that Clark saw a HeadCount booth and thought, “This should be so simple. I can take five minutes on my way from a small tent to a big old party and update my voter registration.” He not only registered — when he got home, he launched a photo project on his Facebook page that highlighting young voters through photography and interviews ahead of the Michigan primaries. He hopes that the profiles of young voters will help educate and engage young people in the voting process. Clark sees a certain willful ignorance and flippancy permeating elections, and he wants that to change. “We are voting and we must vote in the upcoming midterms because we can not take it so flippantly any longer. It is ours to decide,” Clark said.

Richard Fry, senior researcher at the Pew Research Center, says that younger generations have not always been absent at the polls. “When they were 25 to 29, the Boomers typically turned out at 36 percent at midterm elections,” said Fry, while Millennials, at the same age, have turned out at about 26 percent. “So what’s apples to apples is the age, but what isn’t apples to apples is that turnout is very much influenced by the midterm election — by what the issues are, maybe who the candidates are,” said Fry. And when elections can be influenced by things as benign as the weather on election day, the outcome of midterms in particular can be difficult to predict.

Fry said that the shifting racial and ethnic composition of the Millennial generation might also be adversely affecting turnout. According to a January Brookings Institute report, “the millennial generation, now 44-percent minority, is the most diverse adult generation in American history.” But historically, whites turn out to vote in greater numbers than minorities. This isn’t a hard-and-fast rule, however; it’s a trend. For instance, in the 2012 presidential election, 66 percent of black voters turned out compared to 62 percent of white voters, and some younger people are hoping to generate the same momentum ahead of this November’s midterms by volunteering for candidates, registering voters, and even running for office themselves.

“Young people haven’t been voting because there hasn’t been a reason to vote,” said Nasim Thompson, the communications director for Justice Democrats. “The field is usually filled with the same manufactured candidates, who run a weak campaign that lacks the vision and authenticity needed to pull people out of their homes and to events and the polls. If Democrats want to win, we need to get on the offense with a bold message that fights for working-class Americans and energizes young people and non-voters to turn out.”

Thompson thinks that young people are going to turn out in November because candidates like Ocasio-Cortez, who defeated the incumbent Democratic Caucus Chair Joe Crowley in a stunning primary upset in June, are entering the field with a bold message of urgency.

Ocasio-Cortez told The Outline that her campaign targeted young people, and that connecting with them was simply a matter of connecting with her own generation. “We talked about student loans, we talked about climate change, we talked about the things that our generation is going to have to deal with. Young, politically-active people are my peers, so there are natural political connections there,” she said. And it had astonishing results.

From data her campaign has gathered, Ocasio-Cortez said, “We expanded the electorate 68 percent over the last off-year midterm primary in order for us to win. And the under-40 electorate actually matched the over-60 electorate in our race, which is unheard of,” she added. “It’s up to the people most affected by conservative and neoliberal political neglect to really change this country — and I think that means getting the youth engaged.”

To date, HeadCount has registered around 31,000 voters — already more voters than it has registered in a midterm election year since 2004, when the organization was founded. In 2014, more than half of the voters HeadCount registered were under 25 years old, and 26 percent were in the 30-to-39-year-old category. Of the voters that Headcount registered in 2016, 74 percent of them voted in the presidential election.

“Our voter registration usually peaks around September,” said Aaron Ghitelman, the communications director for HeadCount. “We’ve already broken our 2010 and 2014 totals and we’re not even in busy season yet. We haven’t hit a single voter registration deadline for the November elections.”

Here’s where pulling in young people, both as a voting block and as candidates, is important. “I’ve seen politicians my whole life speak to my grandparents in very crisp and clear ways, where it’s very, very clear that politicians on both sides of the aisle are willing to fight for the issues that matter to, say, my grandmother,” said Ghitelman. “I haven’t seen politicians truly go after youth votes the way that they go after other demographics.”

That’s why he’s excited about the crop of young people in both parties who are running for office. “You don’t need to be 40, you don’t need to have a law degree, and any American has the ability of fighting for the America they believe in,” said Ghitelman. “Young people vote when their issues are on the line. When politics directly impact the lives of young Americans, we vote.”

It’s still too early to discern key demographic trends from this year’s primaries. There’s a significant lag time in obtaining demographic numbers — Fry said he will be analyzing November 2018 data around spring of 2019. In Michigan, more people turned out for the state’s primary on August 7 than any other midterm primary since at least 1978. Still, that number was slightly less than 30 percent of registered voters, which Clark said was both record-breaking and pretty heartbreaking.

“We have all the choice but no agency,” said Clark. He sees the limitations of a generation addled by student debt but represented by millionaires and gerrymandering as key things that keep young people from feeling like their votes make a difference. “Our persistent attention to the diminishing weight of our vote is the greatest barrier to our participation.”

Even amid those stark realities, Ocasio-Cortez still sees the work being done this election cycle as a win no matter what. “I think a groundswell of progressive wins from folks like the first Muslim woman and first Palestinian-American future member of Congress, Rashida Tlaib, and James Thompson rocking Kansas are really high points of the political year. Abdul El-Sayed’s bold, impressive performance at transforming Michigan’s electorate is something that will pay dividends for years to come,” said Ocasio-Cortez. “People in local districts new to politics are now organized and awake. You can’t un-organize them — so we’ve already won.”