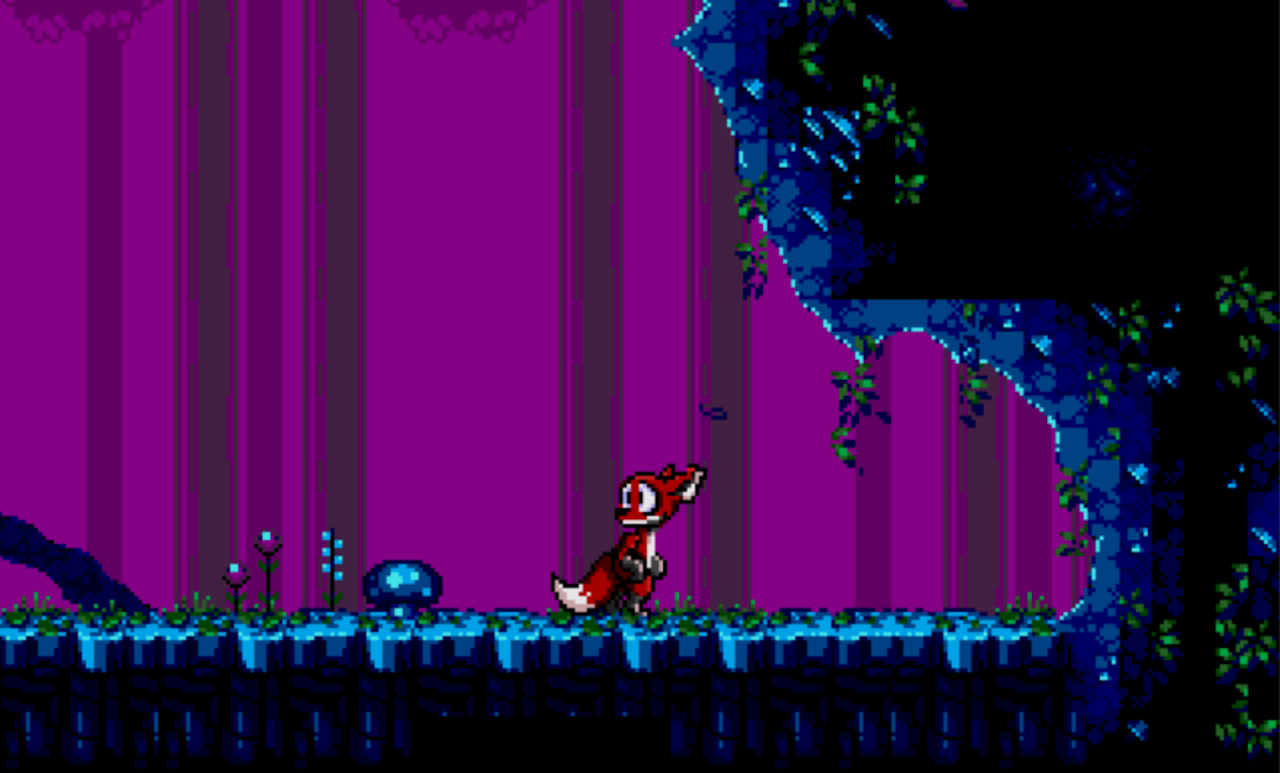

Tanglewood is a glitch in the matrix. As only the second video game released on the Sega Genesis since it was discontinued in 1997, it shouldn’t exist, but it does — a humble, beautifully realized 2D adventure platformer. Go on the game’s website and you can purchase a boxed copy of the game — real cartridge, real manual — to pop into your Genesis, should it still exist at your mom’s house. If not, there’s always the digital-only Steam version. Boot up the game and you quickly inhabit Nmyn, a cute woodland creature who must find its way through an ominous forest back to its family. Strange creatures lurk amongst the 16-bit undergrowth and the tree canopy provides ample opportunity for carefully judged leaps. It radiates with the orange halcyon glow of a CRT television set — nostalgia beamed direct to the brain.

To put it another way, Tanglewood is the purest expression of a video game industry gripped by retromania. In 2010, the music critic Simon Reynolds took aim at the pop industry’s obsession with regurgitating the recent past in his book, Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to Its Own Past. Reynolds swiped at the rapidly unfolding reissue craze, the revivalism and reproduction of historic genres, and investigated how the internet enabled the preservation of musical artifacts in the collective memory. If we’re so fixated on the past, Reynolds contested, then how can we possibly conceive of our future? The late cultural theorist Mark Fisher, a friend of Reynolds, took the ideas further and suggested that the pervasiveness of capitalism limits our means of creating new outlooks. Retromania, ironically, is a means of maintaining the status quo.

The video game industry used to distance itself from such retro-revivalism, instead billing the medium as the harbinger of twinkling technological innovation. In 1991, a Star Fox Super Nintendo commercial promised the future with its FX Chip and the accompanying tagline, “Why go to the next level when you can go light years beyond?” Two years later, a commercial for the Sega CD (an add-on for the Genesis itself) promoted the hardware as a transcendent blast into video games’ rock and roll future. Then, in 2000, Sony dubbed the PlayStation 2’s processing hardware the “Emotion Engine,” a slick piece of marketing which, to the layperson, resulted in slightly smoother, shinier graphics.

Fast-forward to 2018 and video games seem to have forgotten they used to be the future. Retro-facing games are big business, be they rereleases of older titles, repackaged “classic” consoles such as the NES and SNES Mini, or games that self-consciously ape their forebears to such an exacting degree that they’re nigh on indistinguishable from the original. The internet has just lost its shit to the announcement that Dark Souls Remastered, an update of a game originally released in 2011, is coming to the Nintendo Switch this October. The internet lost its shit earlier in the year when Bluepoint Games delivered a crystalline HD-ified version of the classic PlayStation 2 adventure game, Shadow of the Colossus, originally released in 2005.

This type of nostalgia-fetishism extends to the original PlayStation. Players who grew up with that console now get to replay childhood favorites in a crisp resolution befitting the hyper-resolution-ification of the modern moving image. Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy is one such favorite, a remastered collection of three Crash Bandicoot games released between 1996 and 1998. Freed from the shackles of an exclusive publishing deal with Sony’s original hardware, the game’s been released on all of the current major consoles, subsequently shifting millions of copies since June 2017. Spyro, another would-be PlayStation mascot, is getting a similar remastered trilogy this November with Spyro Reignited Trilogy. Its release will simultaneously breathe new life into the purple, hopping dragon, while also enshrining its legacy in the annals of video game history.

Consider Hollow Knight and Dead Cells, two of 2018’s highest rated Metacritic games. Each is essentially a throwback title, riffing on the immeasurably long shadow of Capcom’s seminal 1997 game, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. The occasionally paradigm-busting publisher Adult Swim nonetheless just released Death’s Gambit, a straight-laced piece of nostalgia popcorn that presents an impressively murky rendition of the 2D dungeon crawler. Octopath Traveller, one of the year’s most popular Nintendo Switch games, is another strange, timeless apparition, taking a 16-bit JRPG aesthetic and cramming it with modern special effects and pseudo-3D environments. The entire game appears coated with the sepia glow of an Instagram-esque filter, a not-so-subtle evocation of the game’s imaginary mantra: “old but prettier, old but prettier.”

Tanglewood takes video game retromania to its arguable zenith. The game was created by Matt Phillips using almost exactly the same original development tools from the 1990s. Phillips ran the Cross Products SEGA MegaCD development kit (made in 1993) on a rickety Pentium 2 PC running Windows 95, writing the game’s code in Notepad++ For Win95. When he wasn’t working on the game from his home, Phillips was on the train running all of the above through an emulator on his laptop. Such an approach is a far cry from modern video game development carried out on hulking supercomputers, where finely tuned applications aid an increasingly atomised production process.

The cartridges themselves have been custom designed and machined, while a factory in China manufactures the printed circuit boards. The case packaging comes from a reproduction company that replaces damaged boxes in collections. All of the printed materials are being handled at a local print shop in the north of England. Phillips told me over email that he’s wanted to create a game for the Sega Genesis since childhood. He first encountered the console when he was 8 years old, and explained to me how it’s the kid inside him that wants to see Tanglewood’s release on Sega Genesis. “I’m 32 and a half now but I never did really grow up,” he joked self-deprecatingly from his home office in Sheffield, England.

Tanglewood most closely resembles The Lion King, a video game released in 1994 which existed ostensibly as marketing for Disney’s hit animation. Like Phillips’ game, The Lion King was released on the Sega Genesis, and both are 2D adventure platformers where you control a young four-legged animal (although Tanglewood’s protagonist is significantly less entitled than Simba). The two games also share a beautifully evocative color palette — the deep purples, reds and oranges of sunsets that seem to exist most clearly in our memories.

When I asked Phillips whether he thinks such retromania might limit innovation within the medium, he’s robust in his defense of looking back. “I don't think it limits innovation, I think it promotes it by means of restriction,” he said. ”Innovation has come on leaps and bounds in graphics, audio, networking, and the whole ecosystem in which we buy, share, and talk about games. But a game is still only as good as its design, and nothing about these old systems prevents clever thinking.” Tanglewood, though, as pretty and effective as it is in pursuit of its own goals, is less innovation and more restoration — a meticulously crafted facsimile of its mid-90s forebears.

Video game retromania comes at a moment of existentialism for the medium. At this year’s E3, Sony attempted to codify the soul of the modern video game with titles such as The Last of Us Part II, Death Stranding, and Ghosts of Tsushima — all third person, stoic, story-driven experiences with quasi photo-realistic graphics. Such an approach was recently applied to the traditionally puerile God of War, its story infused with the self-seriousness of fatherhood and an appropriately de-saturated color palette. In many senses, it’s the most conservative AAA video game in years, and it’s lapped up 2018’s critical acclaim like no other.

Sometimes, though, the most seemingly retromanic games look back to say something new. Cart Life, released in 2010, takes a youthful 8-bit aesthetic and wraps it around a simulation about the crushing banality of adult working life. Fittingly, the game is presented in a dreary greyscale. Paratopic, a short vignette-style horror game, uses lo-fi, jagged polygons of the PS1 era to tell a hallucinatory story of capital and smuggling. Its aesthetic, drained of fidelity, makes the game’s grim everyday environments even more unexceptional. Like Fisher’s own expansion of Reynolds’ retromania, Cart Life and Paratopic are concerned with capital, labor and lost futures. While memories of a golden age might sparkle in the mind of modern video game necromancers, these two titles hint at why we’re eerily incapable of escaping the past. Locked into these ghostly suspensions of time, we might ask ourselves where tomorrow has gone.