In 1971, Dr. Seuss published a book you have almost definitely heard of: The Lorax. Generally regarded as a visionary masterpiece of world-making in children’s literature, some predictably called the work out as a didactic, anti-capitalist work of socialist propaganda for its take on the environment’s fraught relationship with corporate malfeasance. In 1984, though, came a lesser-known work, mostly forgotten by time, which advanced long-dormant Seussian politics into an ideological expression that proved too rankling for much of the book’s audience.

The Butter Battle Book, released by Random House in the middle of Ronald Reagan’s transformative presidency, is about the Cold War. More specifically, it’s about the Yooks and the Zooks. These are goofy looking humanoids, clearly of the same species but wearing blue and orange outfits. The blue Yooks (who butter their bread butter-side up) and the orange Zooks (who butter their bread butter-side down) engage in an escalating arms race that features weapons like a "Kick-A-Poo Kid," loaded with "powerful Poo-A-Doo powder and ants' eggs and bees' legs and dried-fried clam chowder," carried by a spaniel named Daniel. The military dick-measuring between the Yooks and the Zooks, conducted by a laboratory of dorky scientists known as “The Boys In The Back Room,” peaks when both sides develop a “bitsy big-boy boomeroo,” a little glowing bean standing in for the nuclear warheads that generations of twentieth-century citizens lived in steady fear of. The book finishes with an impasse, as a Yook general and a Zook general stare each other down over a bitter land-dividing wall, both holding their atomic beans over the ground. This is followed by an ambiguous blank white page that could be interpreted as the end of all life.

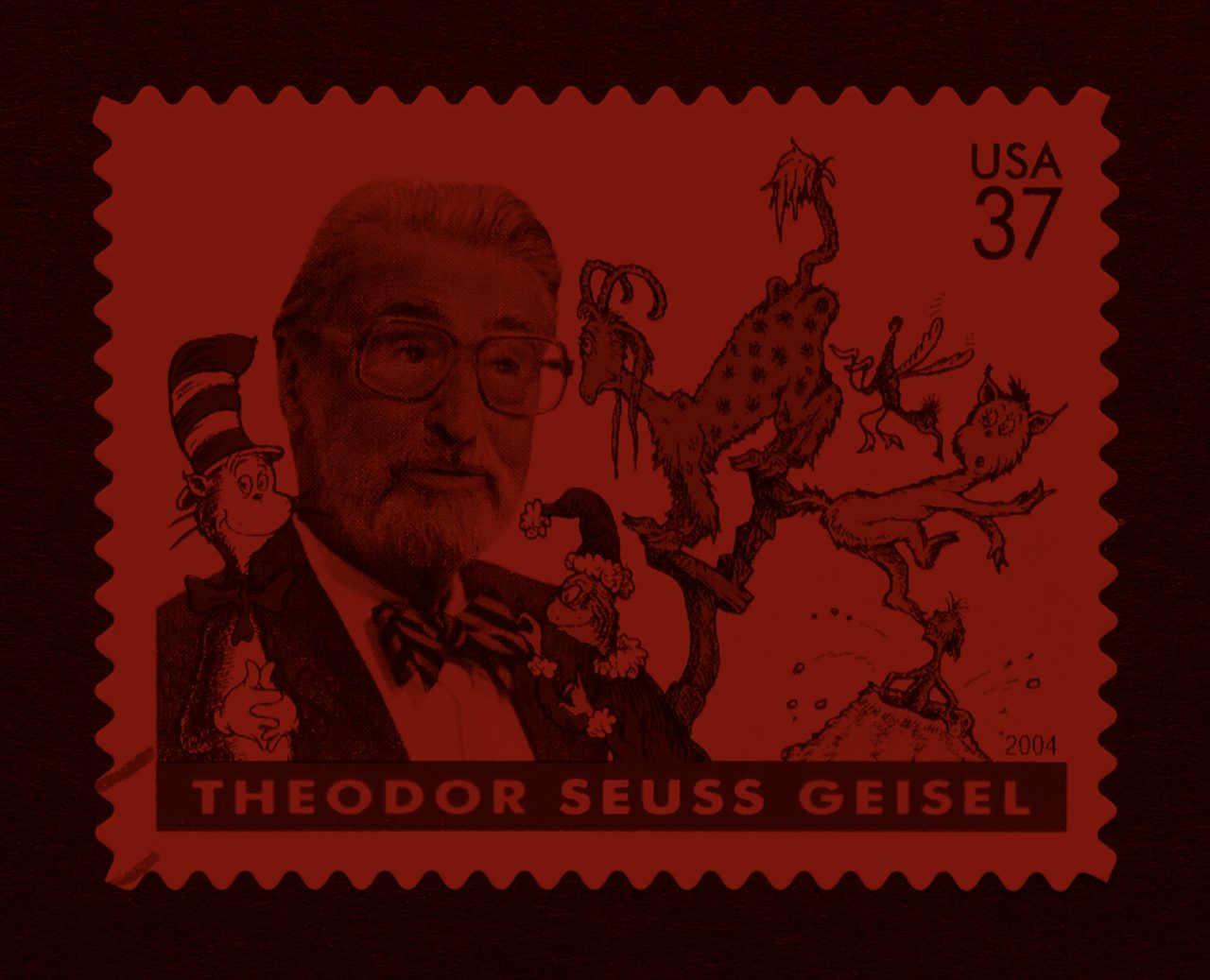

How did this get through to the market? It helped that Random House co-founder Bennett Cerf was the winner of a 1933 legal decision in “United States vs. One Book Called Ulysses,” in which the Southern District of New York determined that James Joyce’s famous work was not too obscene to be imported and sold. Cerf, who had developed the careers of writers like William Faulkner, Truman Capote, and Ayn Rand, was also a massive fan of Seuss, whose real name was Theodor Geisel. Geisel was 53 when he achieved his breakout children’s literature hit in 1957, The Cat in the Hat, gaining the full depth of Cerf’s esteem and a foothold with Random House big enough to have carte blanche in what he taught to kids.

Before The Cat in the Hat, Geisel was a mostly rejected deviant in the form he would later dominate, indulging in far too much fantasy and far too little status quo moralism for most publishers’ liking. He toiled in relative obscurity, his absurd pre-adolescent parables (McElligot’s Pool, Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose, Bartholomew and the Oobleck) occasionally released to mild fanfare as he multi-tasked by writing novels and bizarre smutty cartoons. During these years, he also made fake taxidermy of the types of make-believe creatures he would later be famous for. He was, in other words, a total weirdo, and in his business he was largely treated the way weirdos generally are.

After The Cat in the Hat, his chaotically imaginative books became the standard every other kid’s writer fought to match, as he’d created something so alluring it didn’t need to play by the rules publishers had previously judged him by. A tale about children being rescued from profound boredom by an insane cat, the book was so successful with kids that Random House assigned Geisel an entire imprint. Geisel would curate everything the imprint released, from a variety of authors that would include the Berenstains and P.D. Eastman, but all the biggest hits were the ones he wrote and illustrated himself, most notably One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish and Green Eggs and Ham.

Green Eggs and Ham is noteworthy for being just 50 words long, as Cerf kept challenging Geisel to write unforgettable stories with increasingly fewer words. But it also stands out as having perhaps the most clear lesson of any Seuss book to date: get over yourself, and realize you don’t know everything. Pretty much everyone agrees that this is a good thing for kids to learn. Green Eggs and Ham was an even bigger success than The Cat in the Hat, and everyone was happy.

But when Geisel offered poignant critiques of environmental negligence and the military industrial complex, Geisel would find that his choice of targets made him ripe for critique. First was The Lorax, which was so fundamentally and undeniably successful that attempts to push back on its moralism all come off as craven and, somehow, even more absurd than the work of Seuss himself. And yet: In 1989, members of the small California town Laytonville tried to ban the book because they feared it would stoke anti-industry passions in children. In 1994, The National Oak Flooring Manufacturers' Association published a truly fucked up counter-book called Truax, mimicking the aesthetics and prosody of The Lorax but casting nature itself as ditzy and clueless (personified by a horrendous looking character called a “Guardbark”), in dire need of some ‘splaining from a stoically rendered, axe-toting logger.

To criticize immoral warmongers in a children’s narrative is nearly as important as teaching them to move past prejudice and try out new things. To write kid’s books that keep conservative columnists mad for 30 years is, to be sure, also unquestionably good.

The Butter Battle Book was less impenetrable to its haters. Some libraries gave in to demands to ban it, but it also just wasn’t as widely read. Its message was deemed timely and compelling enough, nevertheless, for a television special. Geisel counted the cartoon adaptation of Butter Battle, developed by Ralph Bakshi (Fritz the Cat, Cool World) as the most faithful screen version of any of his books. (Geisel, who was fervently against the franchising of his books, would definitely hate all of the Hollywood productions made from his work after his death.) Fatefully enough, the Butter Battle TV special was aired in 1989, five years after the book came, two years before Geisel’s death, and very shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Aided by Bakshi’s subversive streak, there is a portrayal of nationalistic militarism in this half-hour that is especially unflattering. “We spread our bread right,” one of the story’s patriarchs barks indignantly during a song about how the Yooks and Zooks butter their separate bread, beckoning back to the supposed moral righteousness he was taught at “bread-spreading school.”

Said patriarch goes on to suggest that the Zooks, because they butter their bread upside-down, have “kinks in their soul.” He is then shown patrolling the wall dividing the Yooks and the Zooks with a “tough-tufted, prickly, snick-berry switch,” bullying Zook children on the other side. He sings the song of his self-appointed mission in a hilariously bloated manner. The story ramps up into technological ridiculousness when one of the children slingshots the patrolman’s switch, destroying it. At this point “Chief Yookeroo,” performed by a very Reagan-y voice actor, hires the old man to officially represent the Yooks and has The Boys In The Back Room give the patrolman weaponry that is “more moderner yet.”

“With my triple-sling jigger, I sure felt much bigger,” the patrolman says as he leaves the weapons laboratory, wheeling a preposterous device before him. His grin is enormous. The story continues in relatively predictable fashion, with the patrolman falling upward through the military until he is made a general, and with the silliness scaling up toward the inconclusive finale, captioned as “The End (maybe).”

Because of its frightening undertones, brazen handling of literally apocalyptic issues, and dismissal of nationalist rigor, some American and Canadian public libraries went on to ban the book when it was released. The National Review, at the time of the Butter Battle publication, took great umbrage with the philosophy of Geisel’s creation, and continued to smack back at The Butter Battle Book in seemingly every Seuss-related news item that cropped up for decades. Memorably, a pre-Times Ross Douthat worked in a mention of the “morally dubious” core of the book in a 2012 review of the of the film adaptation of The Lorax. In a 2004 article, John J. Miller referred to the Butter Battle spirit as a “perfect emblem of the moral equivalence that neutered so many liberals during the Cold War.”

To criticize immoral warmongers in a children’s narrative is nearly as important as teaching them to move past prejudice and try out new things. To write kid’s books that keep conservative columnists mad for 30 years is, to be sure, also unquestionably good. That The Butter Battle Book, Geisel’s most ambitious moral work, is not readily remembered speaks to how deeply entrenched the industrial tradition of violence is in our culture, and how much resistance one meets when they go after its myths at their irrational roots. Proactively engaging children in the horrendous riddle of mutually assured destruction was aiming high, to be sure, and maybe for most of his audience Geisel simply missed the mark. Looking back at the work today, though, it reads more like a chapter of neglected relevance, dressing down the wastefully masculine soul of warmongering that, despite fall of the Berlin Wall, certainly hasn’t gone away.

This was not a message formed by someone naively detached from the inevitability of global conflict, either. Geisel served in World War II as a highly effective informational video producer alongside future The Grinch Who Stole Christmas collaborator Chuck Jones, the famous Looney Tunes animator. He took immense pride in these wartime videos, which featured a character named Private Snafu educating soldiers in an unforgettably lewd and humorous fashion; in one scene, Snafu shoves a rifle up a Nazi’s butthole. Geisel saw himself, in these days, as fighting the good fight against Hitler, and in his older years saw Reagan’s uptick of The Cold War as hammy, needlessly fear-inducing theatrics.

Before that, Geisel drew political cartoons. In these he went after Congress, Charles Lindbergh, Mussolini, Hitler, and also against America itself, before they entered the war. One of the cartoons critiqued the phrase “America First,” which was then a call for an isolationist approach to the violence taking over Europe and Asia. Decades later, President Trump would revive the words in a way that would presage his aggressive trade war, the country’s latest installation of expensive and arrogant nationalism. The thesis of The Butter Battle Book, rich with echoes of Geisel’s one-frame political works from the ‘30s, is that nothing good lies the way of such one-upmanship. Like good patriots before and after him, Geisel knew how to prod an unchecked nation getting too comfortable with itself, and viciously question the principles at its core. That he was empowered to pursue this mission in the arena of children’s literature is a testament to the singular role he played, and still plays, in our culture; Cerf declared that, of all the authors he dealt with, Dr. Seuss was the only genius. One wonders how he would capture what we see today.

Listen to an interview with John Wilmes for more thoughts on The Butter Batter Book and the history of Dr. Seuss on The Outline World Dispatch.