The score line looks plain at first: Switzerland beat Serbia 2-1 last week in a World Cup group stage match. The Swiss staged a comeback, which added another layer of fun to an already excellent tournament, but the celebrations after both Swiss goals turned the game into an intersection of patriotism, Balkan history, and emotions that rippled across a digitally-linked social fabric.

When Swiss midfielder Granit Xhaka scored his goal, a swerving bottle rocket of a shot from twenty yards out, he ran toward a corner of the pitch, tongue wagging. He interlaced his thumbs, palms to his chest, and spread his fingers.

The gesture mimics a double-headed eagle, and as much as Xhaka’s goal mattered — it tied the game 1-1 for the Swiss and launched their comeback — his celebration may have meant even more. But the Swiss and the symbols weren’t finished.

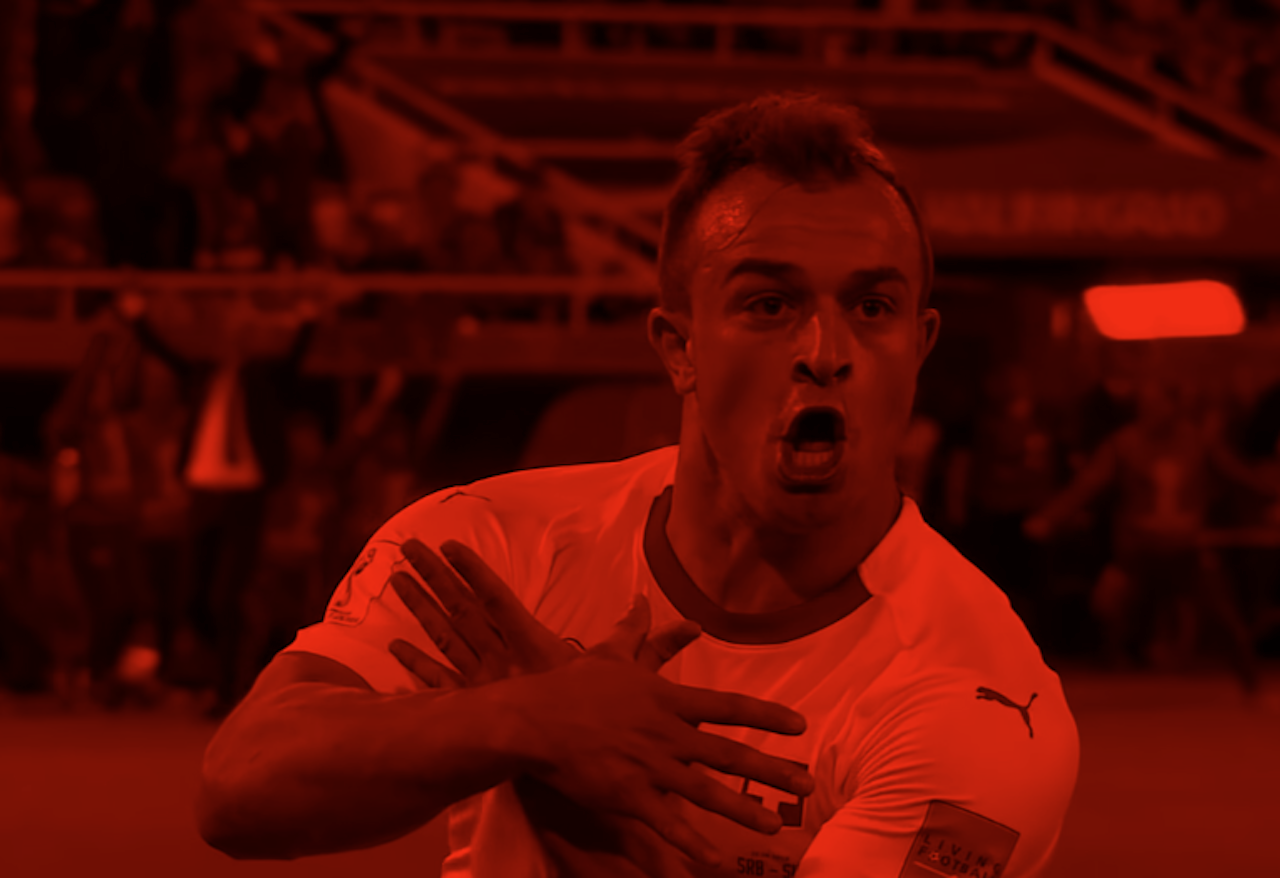

In the 90th minute, Xherdan Shaqiri — the diminutive, preposterously yoked Swiss winger whose Swiss-German nickname (Der Kraftwürfel) translates to “The Power Cube” — scored the winning goal on a solo break, clipping the ball under the legs of the onrushing Serbian keeper. Shaqiri tore off his shirt, sprinted toward the sideline, howled at the crowd and made another double-headed eagle gesture to the crowd. A more amped celebration you will not see.

Two goals. Two celebrations. Two double-headed eagles.

“It felt like Kosovo was playing against Serbia,” said Nertil Çitaku, a resident of Mitrovica, Kosovo.

Xhaka and Shaqiri are both Kosovar Albanian, immigrants and refugees to Switzerland. Xhaka’s father was imprisoned for three and a half years in Yugoslavia for joining a 1986 student protest against the central communist government. After his father finished his sentence, Xhaka’s family moved to Switzerland, where Xhaka was born. Shaqiri’s parents are Kosovar Albanians who fled to Switzerland before the Kosovo War began in 1998. His father worked in kitchens and his mother cleaned offices, with Shaqiri and his brothers helping. Shaqiri frequently sports the flags of Switzerland, Kosovo, and Albania on his boots.

The Albanian flag features a black double-headed eagle on a red field, and the double-headed eagle salute has become a way for Albanians, Kosovars, and members of the diasporas to flex, to represent, to remember. Albanian athletes in other sports have used it after victories, and even Pristina-born Rita Ora has thrown up the double-headed eagle on occasion.

Xhaka’s and Shaqiri’s goals won the game for Switzerland, and helped propel their team into the elimination round (they held mighty Brazil to a tie in the first game and tied Costa Rica in their final game; the Swiss play Sweden on Tuesday). Against another opponent, that would have been plenty. Whatever you might know about history, it’s hard to understate just how important it was that these two players scored against Serbia.

So intricate is the history of the Balkans that one gesture in a World Cup game can open the door to the centuries of empires and dictators who redrew borders and wedged peoples, religions and languages into fixed systems. From the Ottoman Empire to the fall of Communism and the chain of conflicts in the ‘90s known as the Yugoslav wars, local identity has often been lost in the mires of history.

Kosovo, previously a territory of Serbia, became an independent republic in 2008. Many countries, including the US, recognize it as a nation-state. Others, such as the 2018 World Cup host Russia, do not. Albania — while not part of Yugoslavia as Kosovo (then a part of Serbia) was — has a long revolutionary past and is going on its fourth republic. They share a language, a culture and a history. As, Gilbert Agimi, an Albanian university student in Tirana put it, “the term ‘Kosovar’ is a regional term for me.”

If you want to wade into these waters, Rebecca West’s 1941 book Black Lamb and Grey Falcon remains excellent (my first roommate in New York, a Serbian woman, lent me a copy and urged me to read it). On YouTube, you can find the useful BBC documentary The Death of Yugoslavia for a summary of the 1990s. For an even longer view, the podcast “The History of Yugoslavia” covers from the 18th century to now.

But of all things, soccer offers a potent entry point for the outsider to get a sense of the greater Balkan Peninsula. In Jonathan Wilson’s classic book Behind the Curtain: Travels In Eastern European Football, he described the players from the Balkans as the Brazilians of Europe, “self-doubt suppressing imagination and bringing to the surface the cynicism that has always underlain the technical excellence.”

Soccer makes a cloth that ties Albanians living in Boston or Zurich with those in Pristina and Tirana.

In the aftermath of Xhaka’s and Shaqiri’s celebrations, the Serbian Football Association claimed that the mere presence of Kosovar and Albanian flags in the stands was “controversial.” The players were to potentially be punished for “provoking” the crowd. FIFA opened an investigation into Xhaka and Shaqiri’s celebrations last week, and the threat of suspension loomed.

Agimi pointed out the hypocrisy of FIFA’s anti-racism campaigns, saying, “They spend so much energy, money, and time on lobbying against racism, and burn it down to ashes when they fine two Albanians players for simply being proud of who they are. Did they really say no to racism by censoring patriotism? The gesture itself is a gesture of self-respect.”

Zeqir Smalji, an English teacher in Mitrovica, Kosovo, said that the FIFA investigations and Serbian FA complaints were “unfair because of the symbolism; [the double-headed eagle gesture] is not like a Nazi symbol or an ISIS symbol, so to say otherwise is historically unfair and untrue. It represents us as a people.”

It’s hard not to agree. Considering the ugly history of on field gestures, the double-headed eagle feels inoffensive, closer to a symbol of inheritance than of chauvinism. As Smalji said, “[the double-headed eagle] is something that we share; they [Xhaka and Shaqiri] are proud of their roots.”

In comparison, Italian striker Paolo Di Canio’s horrifying habit of on-field fascist salutes (yup, the actual Nazi one) and fascist tattoos didn’t disqualify him from a long career as a player and manager across Europe. And while playing for traditionally Protestant-supported Rangers in Scotland, Paul Gascoigne repeatedly taunted the Catholic fans Celtic by miming play a flute, invoking the marches of the Orange Order, a radical Protestant fraternal order, at a peak of Protestant-Catholic strife in the UK. For FIFA to even consider implicitly placing Shaqiri and Xhaka’s celebrations alongside the explicitly demeaning and violently inflammatory gestures of guys like Di Canio and Gascoigne feels, to me at least, a little sinister and very ridiculous.

The brief FIFA investigation into Shaqiri and Xhaka’s celebrations galvanized the diaspora. Just search “Shaqiri” or “Xhaka” on Twitter and you’ll find photos of Albanian-American Marines flashing the hand sign, people claiming that the players’ symbolic gesture “has done more for Albania than any politician has,” and others pointing out that Serbian players have used a politically loaded gesture for years:

Dear @FIFAcom@FIFAWorldCup Hello from US Marines & NY Senator Marty Golden, this is not a symbol of hate but a symbol of Albanian Pride! #fifa#worldcup2018#switzerland#albanian@granitxhaka@shaqirixherdan#kosova#shqiperia#fifaworldcup2018#serbia#xhaka#shaqiri#Worldpic.twitter.com/Bfz4JnCkIK

— Marko Kepi®️ (@MarkoKepi) June 24, 2018

Xhaka and Shaqiri did more for Albanians in one night than any politician has in 20 years

— Denis (@denis_llagami) June 23, 2018

I find it shocking how Serbian players can do the 'three finger salute' - a sign used by Serb soldiers to celebrate the killing and slaughtering of Albanians during the Kosovo war and get away with it @FIFAcom yet Xhaka and Shaqiri might face consequences for their celebrations? pic.twitter.com/EC2ktpi3Za

— ☘️ (@albooo_) June 23, 2018

You might also say that where the World Cup is being held this year matters too. The increasingly cozy relationship between Putin-led Russia and the Serbian leadership has helped to reignite historical tensions, on the pitch and off.

For instance, if you’d like to read about a comprehensively mad soccer match from 2014, one that involves the crowd stoning players, chants for genocide, a drone flying into the stadium carrying pictures of Albanian national heroes that was pulled to earth and destroyed by Serbian players, I give you one of the wilder Wikipedia pages ever, laying out the events of a UEFA qualifying match between Serbia and Albania that was never finished due to violence. The match was initially awarded to Serbia, and then to Albania, but really, the longstanding conflicts that the match spoke to meant that everyone lost. Lulzim Hakaj, a non-profit administrator in Mitrovica, described the match as “the biggest event in Balkan football history, a tragedy.”

Those tension returned in the hours before the Serbia-Switzerland game. An Albanian Kosovar with whom I spoke sent me a Facebook video, reportedly taken before the match, in which Serbian fans attempt to light a Kosovo flag on fire. Some reports show that some Serbian fans even wore shirts depicting notorious general Ratko Mladic (another horrifying Wikipedia page!) to the game itself.

Xhaka’s and Shaqiri’s celebrations offer a point of inflection, a present-tense digital gift unfurling across the web, giving viewers who tuned in for a soccer match a glimpse of centuries of history, and, simultaneously, giving Albanians coded messages of solidarity and pride. Two guys whose parents fled war, poverty, and political terror made a home in a new place and excelled in front of opposing “fans” who would deny that their people exist. Yeah, it sounds like a sports cliché. Fair enough. Well, in some moments, and for some people, it can happen that way.

loool Xhaka & Shaqiri doubling down with the Albanian eagle celebrationpic.twitter.com/UCugIIe1ZS

— ㅤ🇨🇩🇸🇱 (@6Flavs) June 22, 2018

Even the tenuous idea of allyship ran through the celebrations. After Shaqiri’s game-winning goal, Swiss captain Stephan Lichtsteiner, a player with no familial ties to Kosovo or Albania, threw up the double-headed eagle alongside his teammates. Lichtsteiner later explained that he listened to one of his teammate’s dads, an Albanian, learned the history, and joined in. As Çitaku said, “It looked like Lichtsteiner became Albanian for 30 seconds” FIFA ended up not suspending Xhaka or Shaqiri or Lichtsteiner. It levied minor fines, for which, as the people with whom I chatted showed me, an Albanian GoFundMe raised the funds to pay off merely a day later. (According to the “Updates” section of the page, the organizers “are now waiting for a response from the Swiss Football Federation [as to] whether they will accept the funds raised.” If the Swiss Football Federation turns them down, the organizers write, the money “will be donated to schools in rural areas in Kosovo, for the purchase of sports equipment to be used for physical education classes.”)

Like a lot of American kids my age, I fell in love with soccer during the 1998 World Cup. In the twenty years since, the game and the moments around it never fail to throw me down these passages of history and culture. The entertainment of the World Cup can become a kind of education, if you let it.

The Swiss team — this team of refugees and immigrants and their teammates — gets to keep playing for its future in the World Cup. It’s hard not to root for them. In soccer, as in history, the winners get to tell the story. And this story feels like one that’s more than worth telling.