In California, the brief reign of warning labels that link coffee to cancer might be over. On Friday, a month after a Los Angeles judge ruled that coffee vendors need to disclose that “consumption of coffee increases the risk of harm to the fetus, to infants, to children and to adults,” the state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment reversed the decision. For the nonprofit that brought the dubious lawsuit in the first place, a little-known organization called the Council for Education and Research on Toxics (CERT), this might mean the end of a major payday.

After reviewing over 1,000 scientific studies, the OEHHA declared that, despite the ruling, the chemicals found in coffee “pose no significant risk of cancer.” In fact, “there is moderate or strong evidence that coffee either reduces risk or does not affect risk of cancers.” According to reports, the OEHHA is proposing regulation to undo Judge Elihu M. Berle’s decision. If nothing changes during its August 16 public comment date, cancer warnings on coffee may never see the light of day.

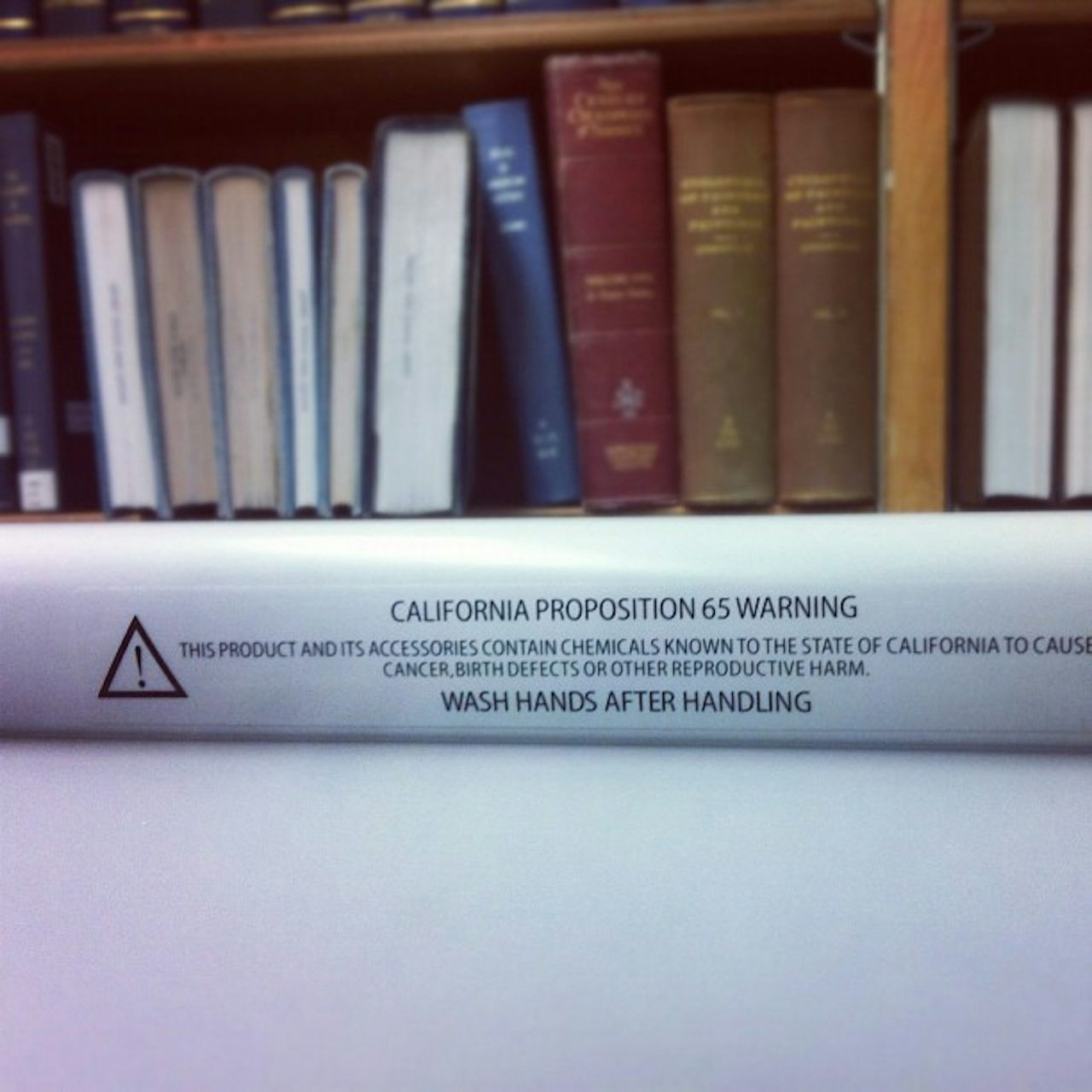

The issue at heart is California’s Proposition 65, also known as the California Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act, a 1986 law that requires warning labels for any of the nearly 1,000 chemicals on its list of materials “known to the State to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.” OEHHA’s focus is on acrylamide, a chemical compound formed in high heat that, according to The New York Times, is found in everything from toasted bread to roasted potatoes to — yes — brewed coffee. Acrylamide is so common that the FDA notes that it exists in roughly 40 percent of all calories the average person consumes, writing, “it isn’t feasible to completely eliminate acrylamide from one’s diet […] Nor is it necessary.” There is also no approved way to brew coffee without it. To be included in the Prop 65 list, relative certainty that a chemical causes cancer or reproductive toxicity isn’t necessary — there need only be a risk.

None of this is new for CERT: the non-profit, which has filed numerous Prop 65 lawsuits since its founding in 2002, has made its name off of cases like these.

CERT is not happy with OEHHA’s decision. After suing more than 100 coffee companies, including Starbucks, in 2010 under the claim that these companies are defying Prop 65 by not disclosing their product’s cancer risk, CERT’s court win last month set them up for massive earnings. Now all that may be in jeopardy.

Despite repeated criticism from scientists, CERT has already earned upward of $1 million from its coffee lawsuit. Prior to last month’s court ruling, companies like 7-Eleven paid their way out early, fearing the financial repercussions of a negative verdict.

And none of this is new for CERT: the non-profit, which has filed numerous Prop 65 lawsuits since its founding in 2002, has made its name off of cases like these.

Though studies found increased cancer risks among rats given a high dosage of acrylamide, “the doses of acrylamide given in these studies have been as much as 1,000 to 10,000 times higher than the levels people might be exposed to in foods,” writes The American Cancer Society. Prop 65 does not account for these discrepancies.

The OEHHA’s move to override the court decision — only the second time an exception has been made — comes after nearly three decades of lawsuits brought under Prop 65, some of which have resulted in similarly dubious health warnings.

In 2002, twelve years after acrylamide was first added to Prop 65’s chemical list, CERT filed the first ever lawsuit related to acrylamide — against McDonald’s and Burger King. Raphael Metzger, the attorney on the case, argued that McDonald’s and Burger King had violated Prop 65 since January 1990 for failing to warn customers that their French fries, which contain acrylamide, pose a cancer risk. CERT won the case easily, and in July 2007, Burger King paid out $1,250,000, including $700,000 in attorney fees to Raphael Metzger. McDonald’s, meanwhile, relinquished $693,500.

Motivated by the success, CERT sued Gerber, Kroger’s, Toys R Us, and Nestle for the acrylamide in their baby food products and CVS, WalMart, Johnson & Johnson, L’Oreal, and countless others for a similar infraction with the chemical 1,4-Dioxane in body lotions.

CERT launched its landmark coffee lawsuit in February 2010, claiming that Starbucks, 7-Eleven, Dunkin’ Donuts, BP America, Yum Yum Donuts Shops, Nestle, Peet’s Coffee, and countless other corporations have been violating California’s Prop 65 law since June 2002 by selling coffee in California without warning labels. Given that fines under Prop 65 approach $2,500 per day, CERT set itself up for a major payday. Up until Friday, the coffee case was poised to be the biggest yet for the secretive non-profit.

CERT doesn’t have a website, a social media account, or any notable public presence, despite having won million-dollar judgments by suing corporations. However, files from the California Secretary of State show that in May 30, 2001, four people co-founded the non-profit: C. Sterling Wolfe, a former environmental lawyer; Brad Lunn; Carl Cranor, a toxicology professor at University of California Riverside; and Martyn T. Smith, a toxicology professor at Berkeley.

In 2016, The Hill described Martyn T. Smith as part of a “revolving door of activist groups and those who profit by disparaging chemicals” who tend to testify in court with “undisclosed conflicts.” C. Sterling Wolfe is a one-time litigator who stopped practicing environmental and fraud law in 1997 to pursue a small-time acting career. Among his roles is the uncredited “Frozen Celebrity” in Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery and John Malkovich’s aide in the Angelina Jolie-led Changeling. In the company’s articles of incorporation, CERT attorney Raphael Metzger was listed as the official contact person, and 2016 tax filings list Metzger’s law office and phone as the business contact info. (CERT now has a different phone number.) Lawyers are cautioned against — and, in some states, banned from — sharing office space with non-lawyers, especially their own clients, because of conflict-of-interest issues. But none of this CERT disclosed in court.

“It’s hardly a model of transparency,” Nathan Schachtman, a lawyer who specializes in science and the law and who has previously published blog posts about CERT’s practices, told me.

CERT has also filed amicus briefs in support of at least two of CERT’s co-founders, including in a 2011 court case. When Smith and Cranor had their testimonies thrown out because, according to the court, their evidence “lack[ed] sufficient demonstrated scientific reliability to warrant its admission,” CERT filed a brief in support without disclosing that Smith and Cranor were co-founders. “That deepens the conflict of interest,” said Schachtman. Neither Smith nor Metzger responded to The Outline’s requests for comment.

And despite the mention of “education” in CERT’s name, there is no record of any attempts to educate the public on toxics, aside from donations to the Berkeley-based Green Science Policy Institute. Otherwise, the money that the non-profit has made — last year, it totaled to $137,354 — appears to have been funneled directly back into founder Martyn T. Smith’s research. Multiple studies he contributed to list CERT as a major source of funding, and a Google Scholar search reveals all the studies CERT has funded appear to have been written by either Smith or one of his UC Berkeley students.

“People who read the articles [...] are not going to know the litigation of provenance of that money. They’re going to see it as, ‘oh, that sounds like some charitable not for profit agency,’” said Schachtman. “They don’t get a meaningful disclosure without being told that CERT is an agency that Smith is a founder of, that he testifies for,” and that makes its money from litigation around chemicals.

California voters first adopted Prop 65 in November 1986. The law, which was pitched as a way to minimize the risk of cancer and birth defects, has already been tweaked on multiple occasions. In 2017, after previously criticizing the large number of individuals bringing “frivolous ‘shake-down’ lawsuits,” California Governor Jerry Brown signed an amendment — which went into effect this past January — that requires the attorney general’s office to review the merit of a Prop 65 lawsuit before it moves to court.

Though other states have laws requiring that employers warn of potential exposure to carcinogenic chemicals in their workplace, none is nearly as pervasive as California’s. Unlike the rest of the country, California mandates warnings about chemicals that could be found potentially anywhere — in food, drink, outdoor environments, homes, and more.

CERT isn’t the only organization to discover the monetary payoffs of bringing chemicals lawsuits — regardless of their scientific basis — against major corporations. In California, Metzger and CERT are part of a larger network that environmental lawyer Joshua A. Bloom described in a Law.com article as “a cottage industry of citizen plaintiffs and attorneys, some of whom have been enriched by manipulating the statute [Prop 65] to their advantage.”

Under Prop 65, anyone can bring a lawsuit — and, if they’re successful, financially benefit from it. Sued companies pay out roughly 25 percent of their fines directly to the plaintiff (the other 75 percent goes to the state).

Citizens who sue under Prop 65, known as “private enforcers,” have made as much as $100,000 per year bringing lawsuits. In 2013, KQED reported on Whitney Leeman, an enforcer who had filed 232 notices against California businesses. To the tune of roughly $350,000, Leeman pointed out the lack of warning labels for everything from “pthalates in greeting cards” to “benzoanthracenes in grilled hamburgers.”

But companies found to have violated Prop 65 give even more to the plaintiff’s attorneys, who pocket massive legal fees. According to Bloomberg, in 2016, Prop 65 lawsuits resulted in $30.2 million in settlement money, and an entire $21.6 million (72 percent) of that went to the plaintiffs’ attorneys. Lawyers like Metzger and Cliff Chanler at The Chanler Group, who has settled cases with Pepsi and who told KQED that Prop 65 represents “more than a majority of our firm’s caseload,” are raking in millions.

Prop 65 cases are easy to win. As soon as a lawsuit is filed, the burden of proof is placed on defendants to show without a doubt that their product poses “no significant risk level.” Meanwhile, according to Bloom, “all the Proposition 65 plaintiff needs to show is that the defendant has 10 or more employees, a chemical listed under Proposition 65 is present in the product, and a consumer or user of the product would be exposed to that chemical.”

In fact, though Prop 65 allows plaintiffs to recuperate the money they spend filing the case, there is no such provision for a defendant even when they win. “That is because courts have interpreted Proposition 65 enforcement to confer a significant benefit to the public,” Bloom writes. Because attorney fees are high and the potential benefits of winning are minimal, many companies — including 7-Eleven and 12 others in the coffee lawsuit — opt to settle rather than go to court.

Those bringing Prop 65 lawsuits have made the warnings so ubiquitous — they’re now on everything from Brussels sprouts to plastic rulers — that a 2016 study from the Harvard Business Review identified Prop 65 fatigue: “The warnings are so prevalent in California that they are likely ignored by many,” the researchers wrote.

The coffee lawsuit is only the most recent to shine a light on Prop 65 abuses and the organizations like CERT that have made their livelihoods profiting off of it. In addition to the $899,999 (including $354,814 for Metzger) that 7-Eleven has already settled for, Yum Yum Donuts paid $249,390, including $125,000 to Metzger, to drop out of the case early. But Starbucks, whose fine has yet to be decided, represented the biggest possible source of income — until, possibly, this past Friday.

Based on the OEHHA report, it’s not immediately clear how, if at all, the OEHHA’s proposed regulation around acrylamide might impact CERT’s coffee payout, which was originally scheduled to be mediated on June 22. But Metzger has already told the AP that he views the OEHHA’s proposal as “unprecedented and bad.”

That’s not entirely true. As Schachtman told The Outline, this isn’t the first time California has made a special exception to Prop 65. After adding airborne crystalline silica, which is found in sand, to its Prop 65 chemicals list in 1997, state officials realized the impracticality of warning people away from beaches. After all, on windy days, beaches qualify as sites of "respirable crystalline silica." So instead of paving over its tourist-trodden beaches, California regulators made a tweak to its guidelines: crystalline silica could only become dangerous if a person is subject to “sufficient occupational exposure” over the period of years.

Schachtman views Friday’s decision in a similar light. “You see a system in a very ad hoc way address a more fundamental issue,” he said. Though OEHHA isn’t shifting how Prop 65 functions, this decision may still be a sign of more changes to come. “It’s a band aid. [But] if you make an exception, it often is the beginning of the end for the general rule.”

That change may come in the form of a federal law. Earlier this month, Kansas senator Jerry Moran introduced a federal amendment urging that warning labels for “consumer products meet minimum scientific standards to deliver accurate and clear information.” The amendment appears to be a direct rebuke of California’s Prop 65. In a statement of support for Moran’s bill, Oregon congressman Kurt Schrader wrote on June 7, “When we have mandatory cancer warnings on a cup of coffee, something has gone seriously wrong with the process.”

Update June 20 2018 1:10 pm: A previous version of this article stated that the OEHHA was removing acrylamide from its list of Prop 65 chemicals; the chemical remains on the list. “The proposed regulation only applies to the health effects of coffee consumption,” says the OEHHA.