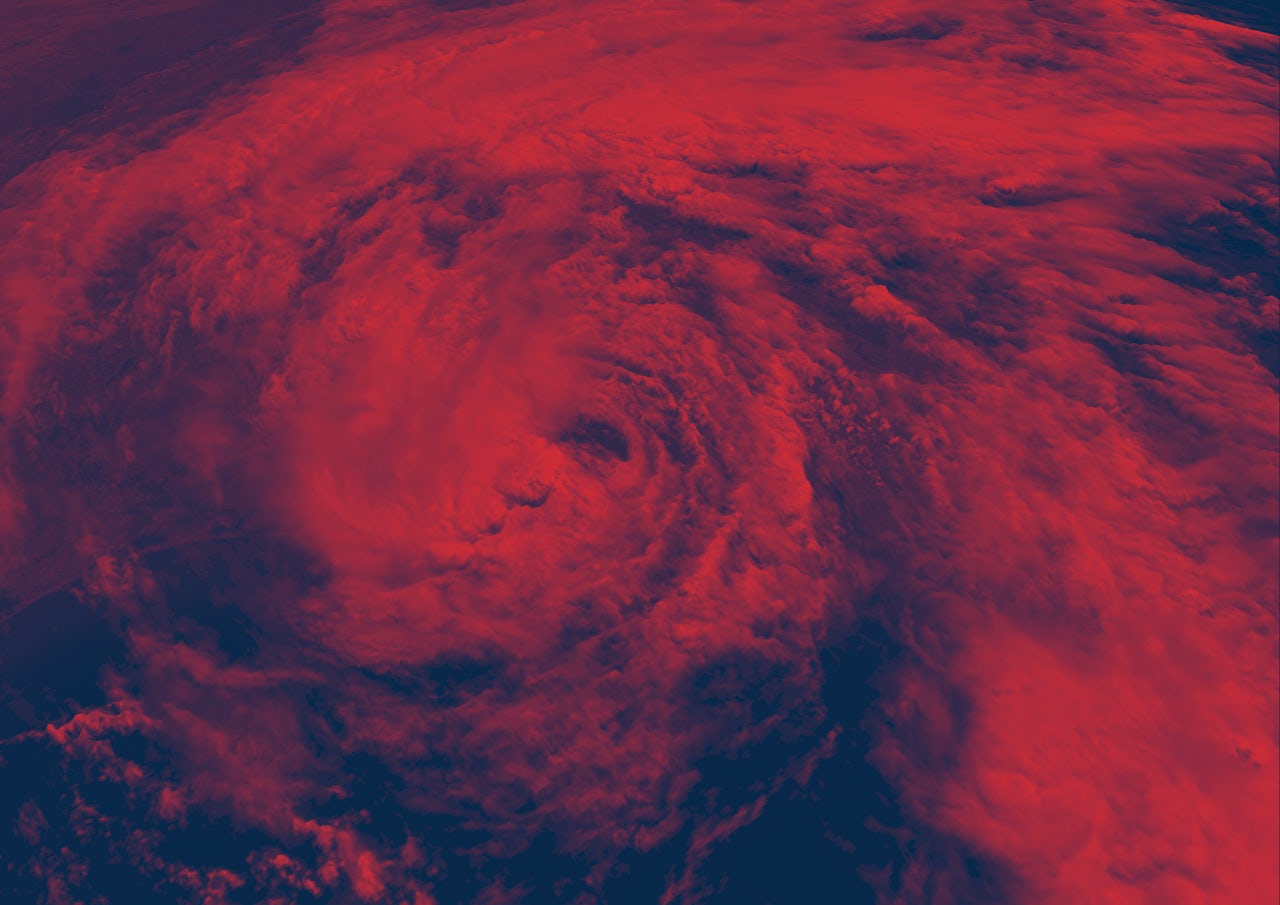

When hurricane Harvey collided with the eastern coast of last year, it belted into over 29,000 square miles of land with more than 20 inches of rain. One area of Houston, Texas—the city hit hardest by the storm—got 48.2 inches of rain during that event alone.

One of the reasons that Harvey was able to generate so much power sounds innocuous: it was a very slow-moving storm. Now we know that Harvey isn’t an outlier, but a part of a long-term trend. According to a research letter published in Nature Wednesday from James Kossin, a scientist for the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the speed with which tropical cyclones in every ocean around the world move forward through the water has been slowing down for almost seventy years.

Slower storms linger near coastlines, allowing them to pump more rain into an area, making a lethal flooding situation even more dangerous. Out of all American deaths directly related to tropical cyclones (or hurricanes), on average, 88 percent are caused by saltwater and freshwater flooding.

“The amount of damage that the wind does is a function of not only the speed, but duration,” Kossin told The Outline in a phone call. “The longer you place a structure in stronger wind, the more damage it’s going to incur. So the three-pronged attack of tropical cyclone—which would be wind, saltwater, and freshwater—would all be increased by this slowdown.”

According to the research letter, climate change doesn’t just make extreme storms like hurricanes more likely. It’s also likely worsening the worldwide hurricane slow-down problem. We just don’t know how much.

Climate change ups the amount of heat that our air and oceans take into their systems. Since heat powers the exchange of water between air and water, this means that climate change is super-powering rain, unnaturally churning and unwinding certain ocean currents and wind patterns. Kossin told The Outline that tropical cyclones are very sensitive to all of these changes to the atmosphere.

“Cyclones are passive in the way they’re simply carried along in the wind, a little bit like a cork in a stream,” Kossin said. “So if the winds are changing, the tracks of those tropical cyclones should also be changing.”

In essence, the global hurricane slow down is in line with what we know about climate change, and how it affects the atmosphere. But Kossin emphasized that we still don’t know exactly how much of this slow down we can blame on climate change.

Granted, we’ve known for a while that slower storms are able to dump more rain on an area of land. But until now, the connection to hurricanes and tropical cyclones wasn’t clear or explicit. Kossin’s research letter tells us that storms in different areas around the world are expected to slow down at different rates. Between 1946 and 2016, cyclones in both the North Atlantic and Pacific oceans slowed down by 20 percent. Storms in the West Pacific ocean—home to Indonesia, Australia, and various small island nations—slowed down by 15 percent.

Kossin also told The Outline that over the next several decades, we can probably continue to expect slower, deadlier hurricanes. Our storm forecasting methods may improve over time, but this long-term trend is already in motion. “We’ve gotten very good at forecasting individual hurricanes and tracks, we have a pretty good idea of where and when they’re gonna make landfall,” Kossin said. “But unfortunately, one of the main factors that the slowdown would carry with it, local rainfall increases, has particularly high mortality risks associated with it.”

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of this new research is that there’s no easy way to act on this knowledge in order to save lives in the short term. City planners and federal administrators can take this risk into account when they consider long-term climate adaptation methods, like water entrapment and seawalls. But everyone needs to be on board, and the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) doesn’t even name “climate change” in its five-year strategic plan.

Put simply, Kossin told The Outline that the scale of the risk outlined in his research letter is unsettling. “Ultimately, we may just be in a place where we might have to accept the risk and go about our lives much like everything else,” Kossin said. “But it’s always sobering when you see a risk that’s increasing.”