I’ve recently been told I should take pictures of my feet.

That sounds kinky, but it’s not. No, this is just a marketing campaign from the spiritual and financial heirs of Adolf Dassler, better known as the Adidas corporation, the 93-year-old sportswear multinational with a $41 billion market cap. Specifically, it’s an email (subject: “You’re about to go viral”) that begins “How to use your sneakers to get likes on Instagram” and ends with me seriously considering a permanent conversion to to flip-flops.

Yes, I like sneakers. Yes, I like likes. When I post a picture to Instagram, usually of my daughter, or sometimes an exotic-looking place I have been, I may refresh the app every few minutes or so for hours afterward, enjoying the steady serotonin drip of all those sweet affirmations. That reward feels somewhat earned, for having generated such adorable and photogenic progeny, or for having had the excellent photographic eye and fortuitous timing to document, say, a cool-looking churro truck in the Balearic islands. Dope kicks don’t factor into the picture. But here are the shoes, telling me they need to be loved — what’s more, telling me they want to help me find love — the logical endpoint of an industry that read Naomi Klein and decided it wasn’t going out with a whimper.

I live in Spain, which means that when I registered for the Adidas online store I used my Spanish mailing address, which means that I get Adidas’ marketing materials in Spanish. (I don’t know if this same campaign exists in the U.S. or the UK, but here in Spain, we do have a reputation for being suckers for our social media.) The person giving me instructions in how to go viral is George, who bills himself as as “expert in Adidas sneakers.” There’s an illustration of “George,” who resembles one of those line drawings you find in airline safety cards, where people calmly insert drop-down oxygen masks first over their own faces, and only then over the faces of their children, before preparing to die in a hellish fireball upon impact with the water.

George is looming over a blue Adidas box with its instantly recognizable logo and three white stripes, throwing his arms wide as if to say “Yoooo, here is a box of sneakers.” His expression is hard to figure out; it’s something like the five-o’clock-shadowed Mona Lisa smile of airline safety cards-cum-sneaker marketing emails.

“In this guide I will teach you how to use your sneakers to get more likes on Instagram,” George says. “Don’t forget to share with the hashtag @adidas!” This last part is confusing for a couple of reasons. Nobody would ever write “#@adidas,” because that would look stupid, and would not even unlock whatever magical database properties the hashtag symbol magically unlocks, because you would just be redirected back to the Adidas account. (I tried, and that’s exactly what happens.) Whoever wrote this mail doesn’t really get hashtags, but that’s fine, because if you have been blessed with this particular marketing mail, it is assumed that you are already a netizen so ‘tag-savvy that you already know how those things work, and there’s no real need to belabor the point. (Fun fact: In Spanish, the hashtag is known as the “almohadilla,” which translates as something like “little pillow,” which, frankly, is a way better term than we native English speakers have for it.)

“Do you have a great photo?” George asks. “Take a look at ‘How to take the best picture of your sneakers,’ or simply improvise!” I thought I was already reading that explainer, but no: A re-read of the e-mail header reminds me this is an explainer on how to go viral. I click on the link for taking the best picture of my sneakers and it just takes me to the Adidas store to… buy sneakers. The little in-flight safety card illustration helpfully shows a diagram of a camera, two feet, and a wall, so it’s pretty clear. Surely, there’s a YouTube tutorial for the rest.

Adidas is terrified of a world in which it can’t offer anything more than the footwear I just happen to have purchased.

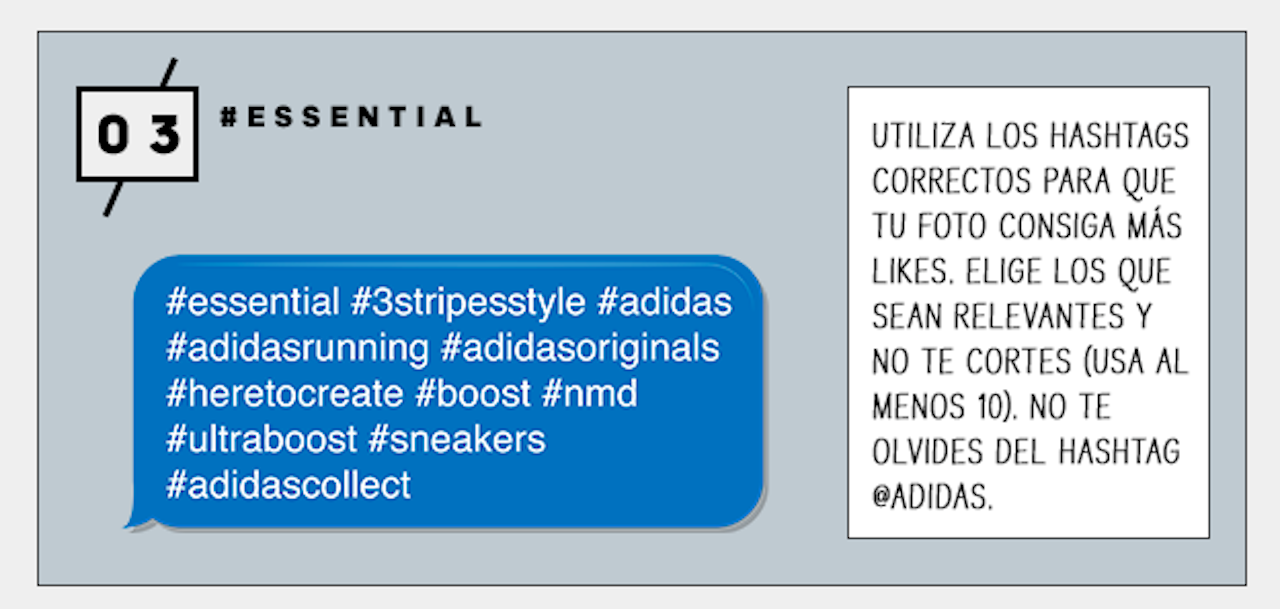

“The important thing is the moment,” George says. He tells me to publish at 12 noon, 6 p.m., or 10 p.m., because that’s when most people are online. That’s a strange thing to say, because in my experience, everybody I know is online all the time, and that is precisely why everybody I know perpetually feels like they are bracing for a plane crash in the ocean. “Use the correct hashtag so that your photo gets the most likes,” he continues. “Choose the most relevant ones and don’t hold back (use at least 10).” (This is news to me; I’m pretty sure I’ve never used more than two hashtags in one place ever in my life, and they were both ironic, just several paragraphs above.) This bullet point concludes, “Don’t forget the hashtag ‘@adidas,’” once again muddying the waters around little pillows and @s.

Further bullet points contain more advice: Tag your location, connect with your friends, and, finally, “Tag other accounts that can share your photo: Accounts like @thesolesupplier and other blogs always share photos, and it’s a good way of getting exposure and gaining more likes.” Here they have a point: Blogs and even reputable publications do love to re-post photos from Instagram, because everybody these days is working for exposure. Freelancers are famous for being forced to work for exposure — dying of it, really, just keeling over right in front of their keyboards. But really, it’s all of us. Our tweets, our posts, our likes and RTs, it’s all just a way of feeding the beast, all of it free labor for Facebook and Apple and Google and all the rest of ‘em bleeding us dry one red dot at a time. Adidas’ marketing email is just the shell-toed tip of the corpse.

There is a point where supposedly cool brands are so desperate for attention that they behave in the least cool way possible; the thirst is real, and it’s funny to witness. What’s disheartening isn’t just that Adidas wants free advertising off the back of my purchase, but the deceptive terms of the whole exchange. C’mere, kid, they are saying: Follow our lead, and we’ll make you popular! We’ll help you get likes! We’ll help you be liked!

At a time when everything has become all about optimizing one’s personal brand, even the company that sells me sneakers is trying to pretend it’s not a sneaker company; it’s offering a kind of personal brand consultancy, right down to telling me what time of day I should post. Perhaps that’s fitting. No company is what it seems to be anymore. Facebook purports to connect you and your friends, but it’s really just a big, opaque data warehouse; Sour Patch Kids set up a house for creatives; Long Island Iced Tea pivoted to bitcoin, of all things. Adidas is terrified of a world in which it can’t offer anything more than the footwear I just happen to have purchased. Eventually it, and its corporate peers, might have to realize that’s all I want.