When the research was published in Nature on May 16, it was like a bomb dropped. A greenhouse gas is billowing into the atmosphere from a source somewhere in East Asia that no one can identify at a rate scientists have never before seen, and it’s ignited a scientific dash to get to the bottom of it.

All countries are supposed to comply with the rules laid out in the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which banned the production of CFCs—chlorofluorocarbons, which deplete the ozone layer and contribute to global warming—with only temporary exception of a few economically developing countries. If everyone fulfills their end of the deal, the amount of CFCs in the atmosphere should gradually wane over the course of several decades. (CFCs can live in the atmosphere for more than half a century.)

CFC levels plummeted through the 1990s, and then stagnated between 2002 and 2005. But in in 2014, mysterious toxic plumes of CFC-11—a type of CFC—began to drift across the Pacific Ocean. Stephen Montzaka, a chemist who studies and monitors CFCs for The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), was shocked.

“I’ve been making measurements of long-lived gases in the atmosphere for nearly three decades,” he said to The Outline in a phone call. “And this is the most surprising and unexpected thing I’ve seen.”

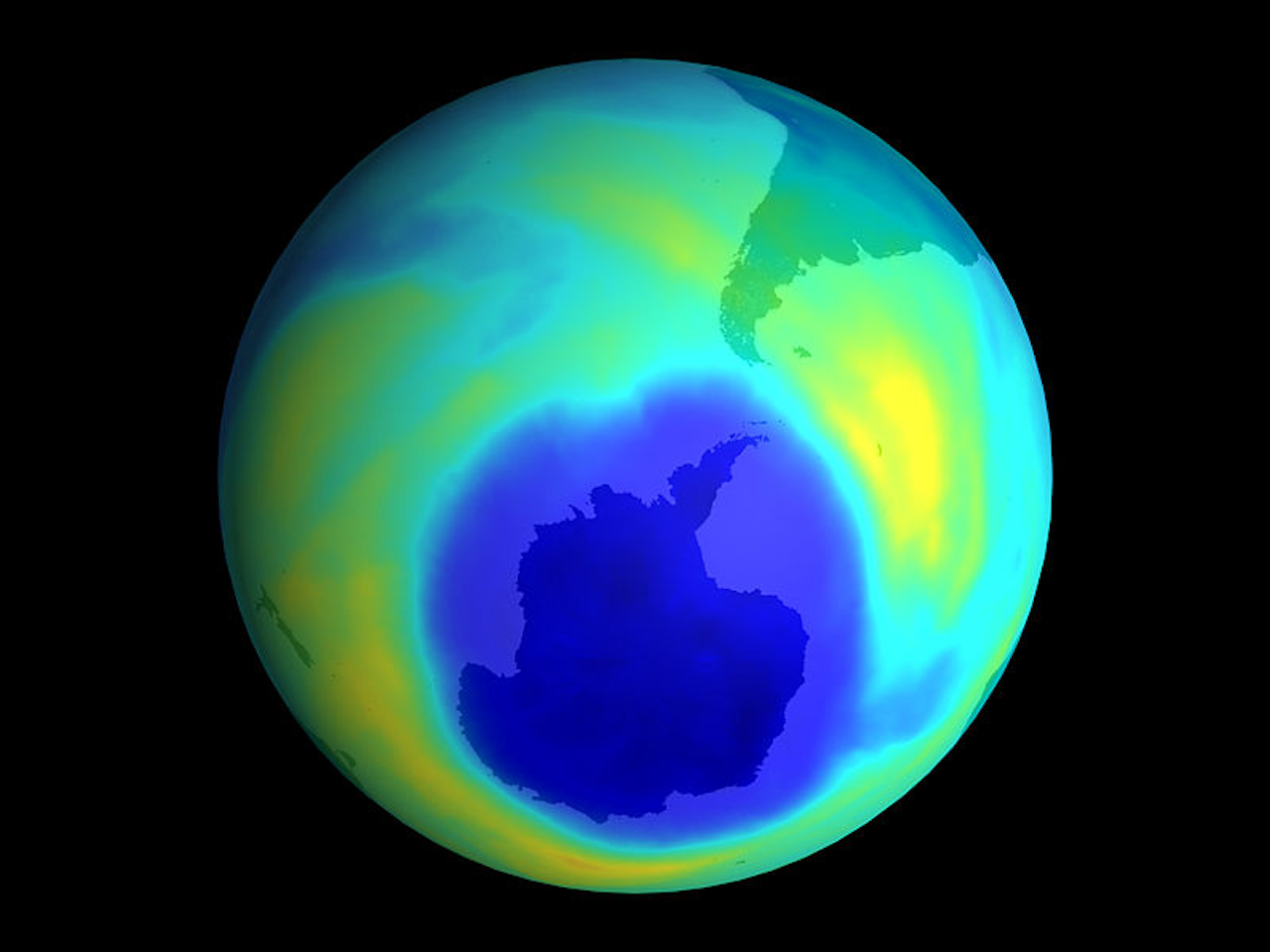

CFCs are monstrous molecules. When the chlorine in CFCs reaches the ozone layer—a part of the atmosphere that absorbs the sun’s ultraviolet radiation, which causes cancer and negative health defects in humans—the chlorine converts life-saving ozone into oxygen. We’ve known this since 1973, when scientist James Lovelock published a landmark study proving that after only using CFCs for a couple decades, a gigantic hole had opened up in the Antarctic atmosphere, allowing deadly radiation to leak in. As greenhouse gases, CFCs are also thousands of times more potent than carbon dioxide, and are able to heat in the atmosphere and warm the earth faster than most other airborne molecules on earth.

So over the next four years, Montzaka collaborated with scientists around the world to try and figure out if there was an anomaly in the data, or if something bigger was happening. “This is the first time that emissions of one of the three most abundant, long-lived CFCs have increased for a sustained period since production controls took effect in the late 1980s,” the research letter reads.

The research letter considers several possible options. Have there simply been natural changes in the atmosphere? Have refrigerators, air conditioning units, and foam packaging—all of which used to be made with CFCs—been rotting in landfills, releasing those CFCs? Have chlorine, fluorine, and carbon been produced, accidentally forming CFCs as a byproduct?

In all of these cases, the study claims, probably not. The amount of CFC-11 they were detecting was simply too high. The most likely scenario is that CFC-11 is being produced, but not reported. Using air circulation data, the scientists were able to conclude the plumes were probably coming from somewhere in East Asia.

“The [CFC-11 levels] increased by 25 percent,” Montzaka said. “And that was entirely unexpected so that was quite a bit of a shock.”

But where, exactly, are these CFCs coming from? Who is responsible? What are scientists and international policymakers supposed to do now?

According to Paul Newman, an atmospheric scientist and co-chair of the Montreal Protocol’s Scientific Assessment Panel, scientists around the world are digging to figure it out.

“The scientists are all running around right now,” Newman told The Outline in a phone call. “Stephen [Montzaka]’s study has sort of lit a fire under a lot of people. They’re going back, they’re taking a look at their data to try and investigate, ‘maybe I got some good CFC-11 measurements.’”

In order to keep these countries in line with the Montreal Protocol’s CFC guidelines, around-the-clock monitoring of CFCs in the atmosphere has to happen around the world. Scientists from the U.S., Australia, Canada, Ireland, Israel, China, South Korea, and various other countries also have air monitoring programs.

These aren’t only scientists, but de facto gatekeepers of international treaties like the Montreal Protocol. Because they share data, cooperate with one another, and synthesize comprehensive results, international treaties can be enforced. They become legitimate.

NOAA has monitoring stations buried in the icy deserts of Barrow, Alaska and the Antarctic South Pole, as well as on a mountaintop above the clouds in Mauna Loa, Hawaii and a lush hilltop in American Samoa. These stations are nearly parallel to one another, like steps on a ladder connecting the global north with the global south.

Even though there’s a lot of scientists up to the task, figuring out the culprit still won’t be easy. “CFC-11, it’s a tough thing to measure,” Newman said. “It’s not just something you go to Walmart and buy an instrument that measures CFC-11.” According to Montzaka, it involves using a pump to suck air from the environment into a canister, which is sent to a lab, where researchers use gas to excite the individual molecules and then sort them by mass and volatility by shooting them with electrons.

At the end of it all, this method separates an air sample into individual chemicals. According to Newman,in order to figure out the exact source of the CFC-emissions, scientists need boots-on-the-ground, hyperlocal measurements throughout East Asia.

“It’s a scientific endeavour,” Newman said. “But people are going to start driving around in cars or vehicles, and hauling out their instruments, and making local measurements to try and pinpoint the sources [of CFC-11].”

Newman believes that within the next year or two, we’ll have a better idea of where this CFC-11 is coming from, and who is emitting it. This is a pretty quick research timeline, but there’s intense interest within the air monitoring community to figure out the source, which could put people in danger if left unsolved.

It’s also an inherently political secret that sets the powerful gears of the Montreal Protocol in motion. Newman said to The Outline that the results of Montzaka’s research challenge governments to hold themselves accountable.

“I think maybe the national agencies in East Asia will go out and take a really hard look at their chemical companies and their reporting procedures,” Newman said.

Ken Jucks, program manager of NASA's upper atmosphere research program, told The Outline in an email that scientific advisors to the Vienna Convention—the predecessor to the Montreal Protocol—can also make research recommendations to countries around the world, and recommend them what type of research to prioritize. But that doesn’t mean this research necessarily happens.

“The Vienna Convention does put a list of recommendations each three years for the [countries] to consider,” Jucks said. “That does not mean that one party or another will actually do it, but we do indeed make recommendations.

But Jucks also noted that the Vienna Convention’s last recommendation report was from just fourteen months ago, meaning that there’s still several months before Montzaka’s paper can be formally considered in the international sphere.

Still, individual countries and researchers are paying attention, so it’s not as if the research is being ignored.

In a phone call with The Outline, Montzaka said that his fear is that people will interpret his research in order to assert that the Montreal Protocol is not working when, in fact, it proves that the safeguards in place to assess the protocol are doing their job.

“Because we used our resources, time, and effort to ensure that we had a measurement system in place and because it is good enough, we were able to detect these issues before they became too much of a problem,” Montzaka said. “The sky isn’t necessarily falling.”