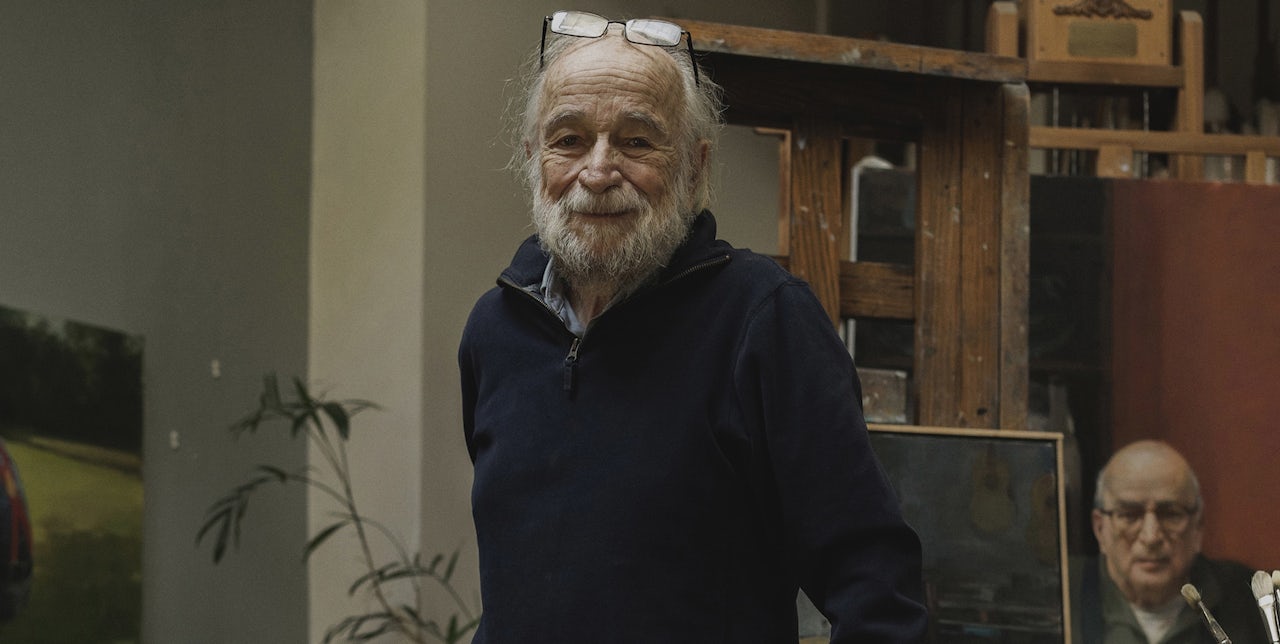

Sometimes, my father, Burton Silverman, age 89, has trouble remembering certain things. He worries about this. My mother, a psychologist, 79, worries even more, parsing his speech patterns and emails for any clinical signs of cognitive impairment. He always hand waves away these concerns, partly for our benefit and partly because there is little to be done.

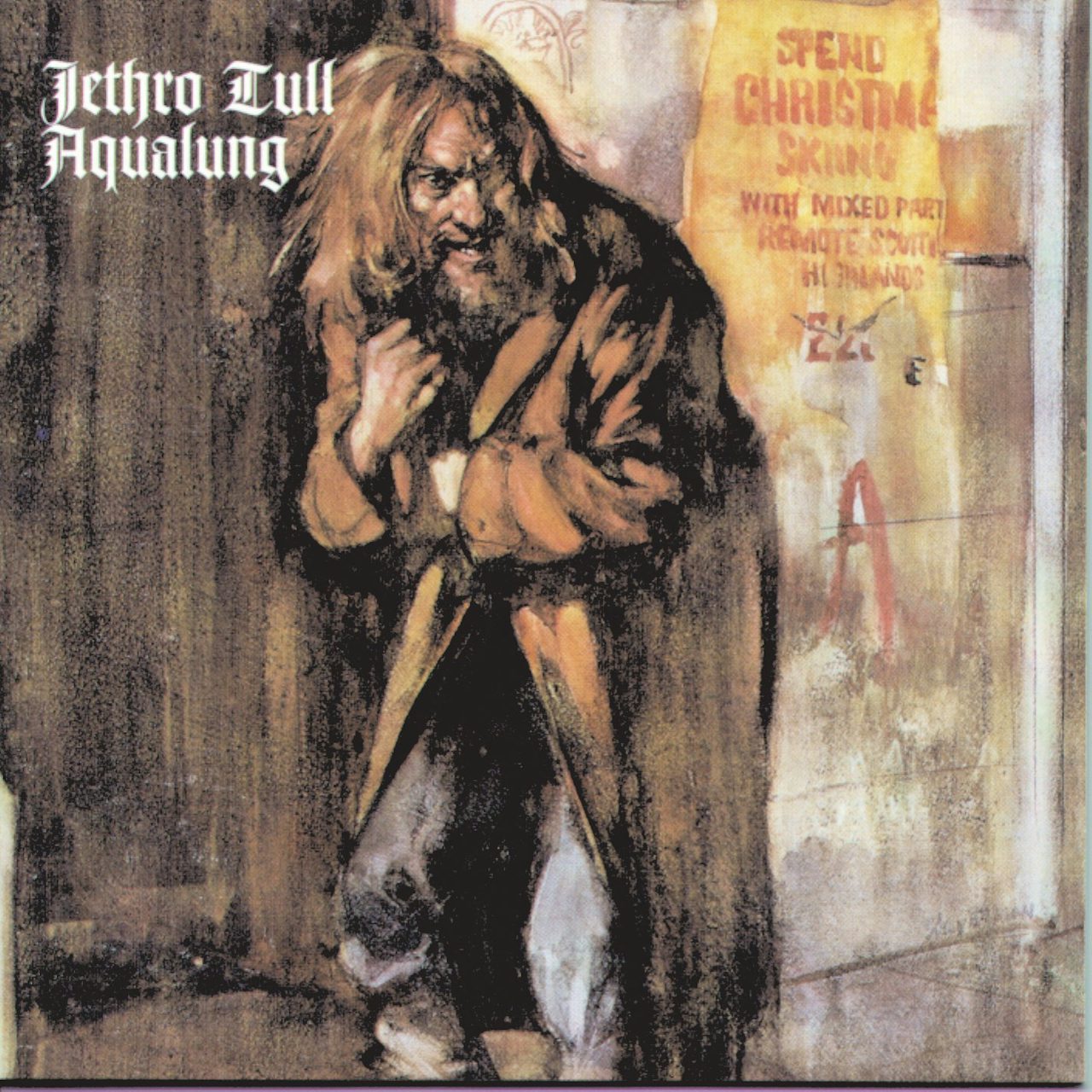

But as some details — the name of a former friend, where he last stashed his wallet — seem to fall just beyond his fingertips, dad’s focus has turned towards something less definable: his career. More to the point, the end of a career that has seen him become one of the more prominent realist painters of his time. And yet, for all the artwork he’s created, the accolades and awards, it bothers him, in a way he can’t really express and may not want to recognize, that one of the first lines in his obituary will mention a “throwaway gig,” from the winter of 1970: the artwork for Jethro Tull’s best-known and best-selling album, Aqualung.

Seven million copies of Aqualung have been sold over the last five-odd decades and the cover has become one of the most recognizable in rock and roll history, migrating from vinyl albums to cassettes, CDs, and iTunes art, plus an unending supply of Aqualung-embossed merchandise. But dad’s earnings had a hard cap. In 1971, Terry Ellis, the co-founder of Chrysalis Records, paid him a flat $1,500 fee for the three paintings which would comprise the album’s artwork, consummating the deal with nothing more than a handshake. No written contractual agreement was drawn up, and, much to his eventual dismay, nor was any determination made about future use.

In the past, dad has huddled with a lawyer or two, hoping he might be able to take the record company to court or claw back a portion of what he felt he was owed. No one felt his case was strong enough to recommend going forward, thanks to the nonexistent contract and older copyright laws which greatly disadvantaged artists. 25 years ago, he even reached out to Ian Anderson, the lead singer of Jethro Tull, to see if he might be interested in joining the cause. Anderson declined. And no matter how much dad tried to put it out of his mind, the paintings would inevitably burble back to the surface. A patron or even a friend would be reduced to a gawking fanboy after learning he painted Aqualung. Or the possible art thief-slash-con man who came crawling out the woodwork in 2012, claiming he’d unearthed the presumably lost cover and hoping to sell the valuable artifact back to dad.

The tale of how Chrysalis Records had done him wrong was turned into somewhat of a running family gag. Given the haggard figure he created, we mused that he might eventually embody his own artistic creation — a destitute, howling figure draped in rags and huddled in a darkened street corner. Buried within this bit of gallows humor lies a nagging truth: There’s a palpable sense of unease and frustration at seeing something he created become immensely popular — define his career, even — only to see his ownership of the work taken away, thanks in no small part to the persistent myths and outright falsehoods that have been told about the artistic inspiration for the cover.

The money and the physical paintings are long gone, but what remains for dad still has immense value: the ability to reclaim the narrative and say what really happened.

Dad’s studio is located on the top floor of my parents’ brownstone on the Upper West Side. It’s a glorious mess. Paintings line the walls from floor to ceiling; others have been crammed into specially-built open storage containers. And then, there are the sketches and source materials which have similarly filled row after row of industrial cabinets. It’s been our plan, going on years now, to take up the Augean Stables-like task of cataloguing all the work in his studio and hunting down the many portraits in the possession of museums and private collectors.

This unpleasant chore has been routinely put off until an unnamed later date by him and me both, partially due to its immensity, and partly because we’re both a little scared about what tackling it might mean. But on a crisp January afternoon, Dad plopped down into a frayed, green chair and we went galloping back to the winter of 1970, when Ellis was in the market for an artist to create the cover of an upcoming Jethro Tull album

Ellis was then at the beginning of his career, but he would go on to produce, manage, or promote a killer lineup of ‘70s and ‘80s rock and roll luminaries, including Led Zeppelin, David Bowie, Rod Stewart, and Pat Benatar. At the Davis Galleries on East 60th Street in Manhattan, he spied some of dad’s work and took a liking to it.

At that point in time, dad hadn’t done much illustration work, save for a few gigs with Esquire and Sports Illustrated. His relative lack of experience showed when, following a quick pit stop at dad’s then-studio on 113th Street and a final meeting in Chrysalis’ midtown offices, the two men hammered out the contours of a handshake deal: For $1,500 (approximately $10,130 in 2018 dollars) dad would deliver three paintings. As to the style and content of the final product, Ellis literally gave him a blank canvas.

“He had no idea what he wanted to do or what I would do,” dad said. This was not uncommon. Dad was often left to his own design by the art directors at various magazines and that degree of artistic freedom — and the promise of steady, well-paying work — helped lure talented draughtsmen into the field. But the lack of a concrete proposal was part of Ellis’s sales pitch, not that dad needed much encouragement. “[Ellis] said, ‘Listen, come to London,’” dad said. “You’ll watch the group in rehearsal. You’ll take a look at Ian Anderson. You’ll sort of get acquainted and you'll get some ideas from it.’’

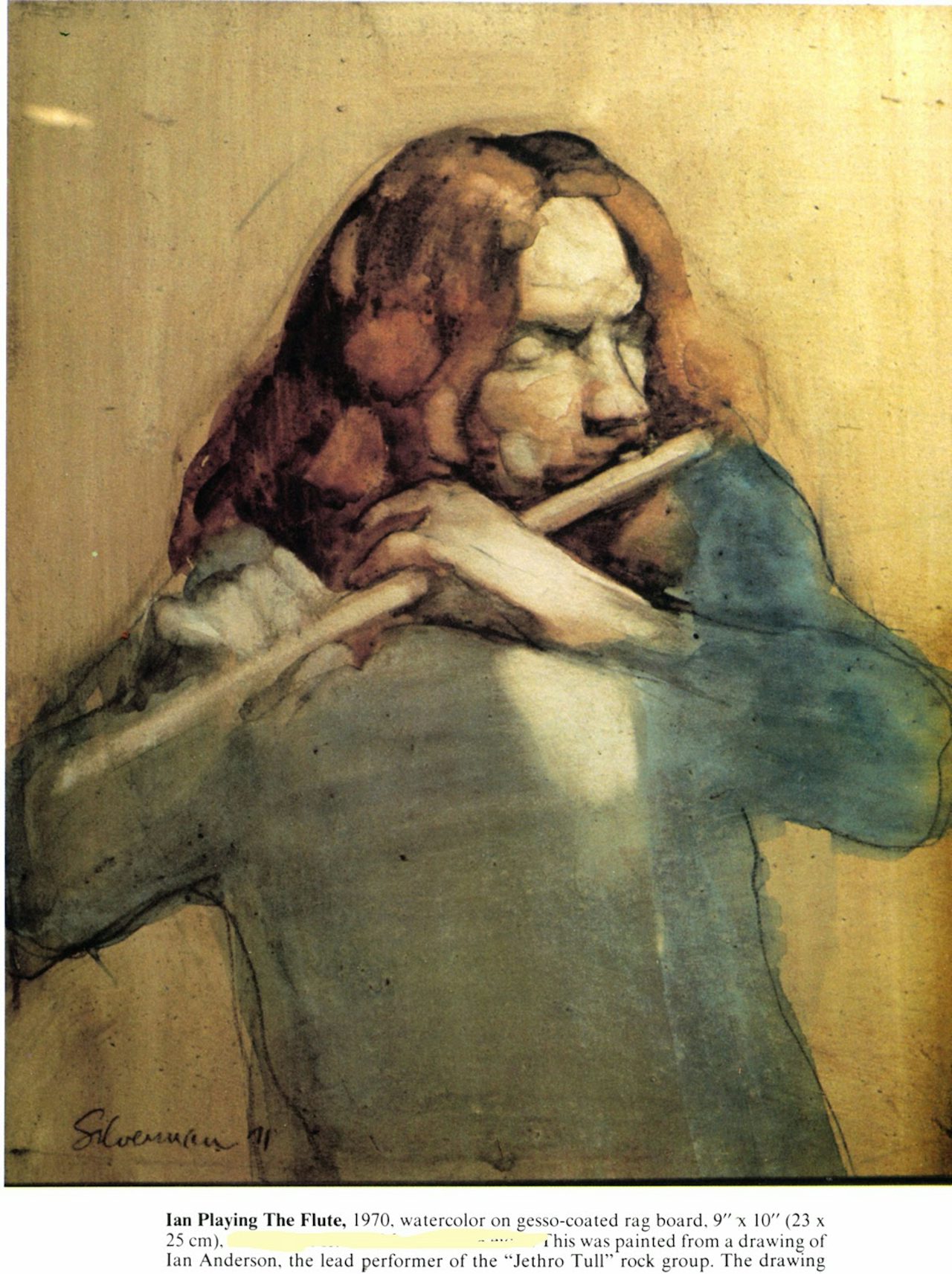

Three weeks later and just before Christmas, dad hopped on a plane, bringing my mother along for the ride. Jethro Tull was rehearsing at Island Studios and so my parents sat and watched while the band played on. Dad cranked out a few sketches and snapped some photos, all of which have since been discarded or subsumed by dad’s haphazard storage and record-keeping system. (One artifact from the trip to London did survive: A watercolor portrait of Anderson my dad finished long after the fact and was reproduced in his book, Breaking the Rules of Watercolor. The original is currently in the possession of an unknown collector.)

Unfortunately, nothing he’d drawn or photographed was usable, nor was the music itself much help, not with stacks of eight-foot high speakers in the studio sending sound pinging off the relatively close quarters. Frustrated, up against a looming deadline, and dealing with a nagging cold, dad returned to his hotel room and splayed out all the potential source material.

The lyrics to the title track kicked his muse into gear. “Aqualung,” to clarify, is both the name of the album and a character in the opening track, described as an “old man” with “Snots running down his nose / Greasy fingers smearing shabby clothes” who’s waiting for the Salvation Army to reopen. Poring over the lyrics, dad recalls saying to himself, “This is a misbegotten street person, an angry man at war with an unjust world, who would yell incoherent things.”

He decided to place the figurant of Aqualung in a lonely, dank doorway, gripping his shabby coat for warmth and menacingly warding off all comers like a cornered animal. He and my mother took to the streets, traipsing around London in search of the perfect, grubby setting. When they found a backdrop to dad’s liking, he grabbed his coat collar and hunched over, while mom snapped a few black and white Polaroids for future reference. For the wild-eyed, rheumatic street preacher-slash-pariah’s facial expression, dad partly used himself as a model, grimacing into a hotel mirror and drawing himself.

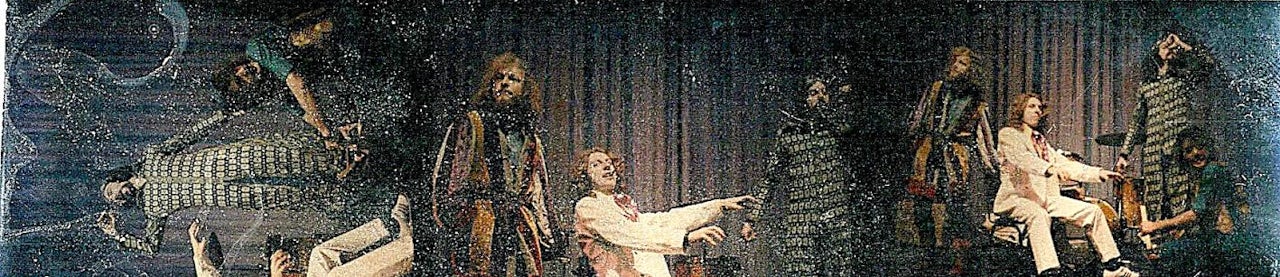

The cover painting and the inside gatefold — a rollicking jamboree derived from Jethro Tull’s ample onstage theatricality and taken from stock photos provided by Ellis — were completed before dad fled London, but he didn’t hand over the back cover until he had returned to New York. It’s a relatively simple image of Aqualung at rest, plunked on the sidewalk with a friendly dog perched by his side, a compositional choice informed, again, in part by the lyrics and partly by dad’s desire to be done with the job. “I was thinking, 'I've just got to finish this fucker,’" he said. After all, “I thought this was a throwaway gig."

In Ellis’ Midtown office, the last painting was delivered. Ellis cut him a check and said something to the effect of, "Oh thanks very much, these are great,” dad recalls.

And that was the end of that, or so he assumed.

“That’s pretty simple. Because it rules.”

According to the band’s website, Aqualung remains their best-selling and best-known album, with seven million copies sold in total. A 40th anniversary edition was reissued in 2011 and a live version in 2005, both of which repurposed the original front cover. In 2012, Rolling Stone ranked it as the 337th best rock album of all time, and “The cover painting gave Seventies kids nightmares,” the review said.

Dave Weigel, the national political reporter for The Washington Post and the author of The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Prog Rock, told me Aqualung dramatically rejiggered the public’s perception of the band, particularly in the United States. Though they’d already built a decent following and had scored a few top 10 hits, they were somewhat pigeonholed as whimsical and folksy British troubadours prone to wearing codpieces onstage. Aqualung made their bones “as a more, I'd say, dangerous band,” he said. “There was an air of mystery they cultivated,”

Why has Aqualung stuck around for so long? “That’s pretty simple: Because it rules,” said Weigel. Moreover, the themes it explores are still quite radical — a quest for spiritual truth, the failings of organized religion, and doubts about the existence of God. Still, “That six note riff at the beginning of [the song] “Aqualung” is in the pantheon of great rock riffs."

The artwork helped. “This is probably the golden age of the rock [album] cover,” Weigel said, and though they ran the gamut from hyper-designed and often surrealistic imagery and photography, Aqualung was of a different order. “This is just a cool painting — a cool rough, impressionistic painting which I think stands out for that reason.”

Ian Anderson couldn’t disagree more. In the book, A Passion Play: The Story Of Ian Anderson And Jethro Tull, he called the front cover, “not very attractive or well executed,” adding, “I’ve never liked the Aqualung album cover; although a lot of people think it’s terrific.” In a 2011 interview with LA Weekly, he called the artwork "messy,” and restated his complaints about it being an unflattering portrait of him (which it isn’t). Aesthetic criticisms notwithstanding, t-shirts featuring the cover art are currently available for purchase on Jethro Tull’s website for $19.98.

But as records gave way to cassettes, CDs, and other formats, followed by an endless stream of Aqualung-emblazoned merchandise from clothing to coffee mugs, dad got pissed. “This is not good,” he said to himself in the late ‘80s, realizing how badly he’d goofed not specifying future use or getting a signed contract at all.

Routinely, friends and strangers alike would gape in awe when they learned he was responsible for the cover of Aqualung. In 1994 he was checking out colleges with my sister, and spotted a full-size poster of Aqualung hanging on a freshman’s wall. Matter-of-factly, my sister blurted out, “My dad painted that.” They left, only to have the poster’s owner come bolting out of his dorm room with a Sharpie in hand, begging for an autograph. “Burton Silverman” is also the answer to a Trivial Pursuit question, dad said. Namely: Who painted the artwork for the album, Aqualung?

Of course, without a contract in hand, he was pretty much screwed. In the early ‘90s, a small glimmer of hope emerged. Peggy Lee sued Disney, claiming she was owed a portion of the profits accrued from the VHS version of Lady and The Tramp, which was released in 1987 and earned $90 million. Lee did voice over work in the film — both the Siamese cats Si and Am and Pekingese Peg — and contributed a few songs, for which she was paid $4,500 in total. The difference was that Lee had an iron-clad agreement and had included a clause stating Disney “retained no right to ‘make phonograph records and/or transcriptions for sale to the public” beyond the initial theatrical release. Despite Disney unleashing the finest legal minds money could buy, the courts sided with Lee and she was awarded $2.3 million.

Dad sought the counsel of Hal Kant, a family friend and the long-time lawyer for the Grateful Dead, hoping Lee’s case might tip the legal scales. Alas, no. Warner Brothers, which had since acquired Chrysalis, would surely follow in Disney’s legal footsteps, Kant explained, using its vast financial resources to draw the proceedings out until dad was hemorrhaging attorney fees — and that’s assuming dad could find a lawyer who thought he had a winnable case.

I spoke with Linda Joy Kattwinkel, an attorney specializing in copyright, trademark, and arts law, and past chairperson of the Northern California chapter of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A.. She explained that when dad and Chrysalis came to a handshake agreement, as long as the paintings were originally considered “works made for hire,” the copyright for the paintings always belonged to Chrysalis, thanks to the 1909 Copyright Act. Copyright laws were amended in 1978, making it more difficult for commissioned works to qualify as “works made for hire,” especially in instances where a contract was less-than-specific. Unfortunately, the courts have heavily favored publishers for cases that dated prior to 1978, which means dad missed the cutoff by a scant seven years.

“It's all going to come back to the same question of whether it was initially ‘work made for hire,’” she said. If yes, there’s nothing dad could do. There’s a miniscule chance dad could argue that he licensed his paintings to Chrysalis while retaining his copyrights. If so, the license would only cover what both parties intended at that time — the album artwork for an LP.

“Most courts, however would assume that the original intent extends to use on future technologies for essentially the same purpose [illustrating the sound recordings], ranging from cassettes to CDs and even iTunes imagery. But when you go off into t-shirts and other kinds of merchandise, maybe that's where the license doesn't quite get there,” said Kattwinkel.

Even so, Warner Brothers would spare no expense fighting the case. When it comes to artists and copyright law, “It’s very messy and it’s very contentious,” she said, “especially for famous works because the companies don’t want to lose their valuable rights to those works.”

If he couldn’t win in court, perhaps, dad surmised, Anderson might be willing to join the (non-existent) battle against Warner Bros, and help win some token equity in the continued use of the painting, somehow. In the fullness of time, dad has come to realize how half-baked this plan was, but in 1991, he penned a letter to Anderson, asking for help. “As a champion of goodness, truth and beauty, would he entertain to put in some kind of word on behalf of another artist,” is how dad describes his entreaty.

Using his corporate stationary and in a haughty tone, Anderson said any dispute regarding royalties and the rights to the artwork were between dad and Ellis. He also doubted that Ellis would fail to spell out future rights in a written contract (he did), yet again insisted falsely that dad modeled the figure on the front and back cover after him, and suggested dad could not “legally hold copyrights in an artistic representation of a real person.”

An artist can maintain the copyright for a representation of another human being, famous or not. But Anderson’s sense of entitlement in the letter, the combination of grandiosity and the instistance on false claims, plus his side hustle selling autographed lithographs — bearing Anderson’s signature, to be clear, not dad’s — on the cover still bugs dad to no end.

The story, as it were, more or less ended there. The idea of a lawsuit was dropped and my dad resigned himself to the idea that the entire body of his work wouldn’t make nearly as much of a dent in the popular cultural consciousness as one album.

Until 2012, that is, when out of the blue, a man called him from a number with a Georgia area code, claiming that he had two of the three watercolors. At the time, he gave his name; my father remembers writing it down, somewhere, but in the ensuing six years he’s forgotten what it was. Let’s call him “The Man From Georgia.”

How had he gotten his mitts on of these valuable and presumably lost works of art? According to The Man From Georgia, his mother had discovered all three of them left behind in a London hotel room. Without knowing their importance in rock and roll history, they caught her fancy, and instead of passing them off to the hotel concierge, she had decided to keep them for herself. The gatefold painting, unfortunately, had been destroyed by water damage, he said. But the front and back cover were as good as new. He offered to sell them back.

It seemed too good to be true. Playing it coy, my dad tried to lowball him, making an initial offer of $500. The Man From Georgia demurred, but the next time they spoke, dad asked again how he acquired the paintings. The Man From Georgia’s backstory suddenly changed. Now, he explained, his mother had received them as a gift from some long-forgotten suitor. All of this began to sound fishy as hell, but still. There was a miniscule chance this wasn’t a ham-fisted con, so my dad strung him along.

The calls continued and The Man From Georgia kept upping his demands. During their final conversation, he asked for $5,000. Dad declined and tried to put the squeeze on him, saying he’d let gallery owners know that the items were stolen, should The Man From Georgia attempt to peddle them elsewhere.

Dad heard — though he can’t remember how and from whom — that The Man From Georgia was not scared off by this quasi-threat and had in fact rung up a few auction houses, attaching the same $5,000 price tag. He tried to call again but The Man From Georgia’s phone number had gone dead. No further communication took place, and there’s no indication that he was able to sell the artwork, if he’d ever owned it to begin with, to anyone else.

In late January, we spent an hour trawling through old emails and datebooks, trying to locate any clues — a scrawled name in a corner, or maybe the old, dead phone number — that could possibly lead to The Man From Georgia. We came up empty.

But he had reached out to one person back in 2012 about the unknown, presumably Southern art huckster: Terry Ellis.

When The Man From Georgia broke off contact in 2012, dad emailed Ellis, asking if he knew anything about the whereabouts of the paintings, if only to determine once and for all whether or not The Man From Georgia’s story was bunk.

A few weeks later, Ellis wrote back, saying how wonderful it was to hear from dad, now 40 years since they last met. He waxed nostalgic about the “crazy heady days!” back in in the ‘70s, much of which spent touring with Jethro Tull and other bands, a schedule that made keeping track of the paintings impossible. The gatefold painting used to hang on his office wall, but it, along with the front and back, had been lost at some point. “I had other pressing issues to deal with at the time,” he wrote, but, “I did have some personal possessions in storage at one of the Chrysalis offices that were stolen — maybe the artwork was among them.”

He ended the email by expressing a desire to get back in touch, apologizing for not being a better steward of the artwork, and saying he’d do what he could to help in their recovery, if possible.

The get-together didn’t end up happening, but Ellis’ curiosity must have been piqued enough to send him rummaging through his storage facility in Saratoga, New York. Both the front and back were nowhere to be found, but the interior painting? It was there, safe as houses.

It was one of the first things Ellis mentioned when he and I sat down to chat at a Le Pain Quotidien not far from the United Nations, on a windy, wet, and generally unpleasant Friday evening in January.

“I think that it was sort of a magical moment between all of us, capturing that image, which on the one hand drew from the song.”

Tucked unto a back booth, far away from the clatter of a chain coffee joint packed with fidgety and loud children, sat Ellis, wearing a tan sweater and button down shirt and looking far younger than his 74 years, even with little more than a wisp of white hair crossing his bald pate. He was charming and affable in a particularly English kind of way: self-deprecating and winsome, and always full of bonhomie.

“I have the interior,” he blurted out dryly, as if it were common knowledge. Similar to to the email he sent dad in 2012, Ellis said he’d been hoarding a bunch of personal items at Chrysalis Records’ old office, and while was out of town on a road trip, the thieves struck. Though they made off with a modest haul, including a slew of old 78s, the interior gatefold painting mounted on his office wall had gone untouched, for some unknown reason.

Meaning, if the two paintings had actually been stolen from Ellis’s office, there’s a non-zero chance that The Man From Georgia’s sales pitch may have contained a kernel of truth. Is it possible that his garbled, ever-shifting backstory was just a clumsy attempt to conceal some level of participation in the receipt and possible sale of stolen goods? Does The Man From Georgia still have the other two paintings now?

In the moment, I was so taken aback I forgot to ask Ellis why he had never called or emailed dad in 2012 to let him know he had the interior painting. But he did describe the creative process that led to the artwork for Aqualung.

“I think that it was sort of a magical moment between all of us, capturing that image, which on the one hand drew from the song. But on the other hand, drew from Ian as well,” he said. “I think it was one of those happy coincidences that all just came together in a very exciting way…[the painting] became the singular recognizable symbol.”

I didn’t press him how the cover actually “drew from Ian” (it didn’t), or get him to pin down what, aside from hiring dad and presenting him with a few stock photos, were his contributions to this “magical moment.” But I mentioned that dad has grumbled about missing out on a windfall and had spoken to lawyers, all of whom told him to let it go.

In response, Ellis said that iron-clad contracts spelling out future use soon became standard practice in the industry, but as to specifying the rights for CDs and posters, “it would never have occurred to me at the time,” he said. “It certainly didn't occur to [my dad] either.”

As our brief encounter was wrapping up, I asked Ellis if he might be able to put me in touch with Anderson, and he seemed happy to oblige. They’re still good friends and talk often, he said, and when one of them meets with a friendly reporter, they’ll tip off the other. “I’ll say, ‘talk to this guy. he’s a good guy,’” said Ellis. Plus, “Ian likes to talk. You will have no problem.”

Four days later, Ellis called me. Unlike our prior meeting, his voice was tinged with unease.

He mentioned that he had spoken to Anderson, who was apparently very perturbed at the idea he would be asked about the paintings at all. Of further concern to Anderson, per Ellis, was that I’d ask him about the letter he sent dad in 1991.

Ellis sounded similarly irked. He grilled me as to what the focus of the article would be, asking why mentioning the nonexistent contract or the rights to the paintings were necessary to tell the story of Aqualung. I told Ellis that if Anderson didn’t feel comfortable discussing either the artwork or the letter, fine; we could limit our conversation to the album.

There was a Harold Pinter-sized pause on the other end of the line. Finally, Ellis broke the tension, saying he’d circle back with Anderson and let me know. I highly doubted that I’d ever hear back from either of them ever again.

I emailed dad about the found interior painting after I’d gotten off the phone with Ellis and he was beside himself.

“What!!!” dad fumed, angered that Ellis had never let him know, especially since he had “retired to the [British Virgin Islands] paradise with the accumulated loot from my record cover.” [emphasis and italics his]

By the end of our exchange, dad calmed down considerably, writing, “All of it is perhaps best left alone.”

And then, to my total surprise, one of Anderson’s representatives wrote back to say he was available and willing to speak with me. Contact information was exchanged; a time for the call was set; press-ready photos and information about their upcoming tour were delivered; and I was also cheerfully reminded to go over the All Too Frequently Asked Questions sidebar posted on Jethro Tull’s website, lest I perturb Anderson by mentioning any of the ”stuff he hates being asked,” the representative wrote.

One such example of an oft-asked and irritating question is: “Jethro Tull and Ian Anderson are amongst the legends of Rock. Why do you think the band has lasted so long?”

Approximately 22 hours prior to our scheduled conversation, the representative cancelled the interview. She passed along this statement from Anderson: “I had nothing whatsoever to do with the project other than posing for some photos taken for his father to work from.” (Anderson did not pose for any photos, per dad.)

I was disappointed. More than anything, I wanted to correct the record, for my dad’s sake if nothing else. Part of me was curious to hear what Anderson might say. Maybe he could admit some measure of foolish pride, or at least see why dad might feel as though he’d been wronged.

But no one, it seems, wants to be confronted by evidence that in any way refuted a version of story they’ve been telling themselves for decades.

That could be said of any of us. It doesn’t matter if you’re a relic of rock’s boomer glory years or an aging artist — it’s unpleasant when a romanticized or fictionalized notion of self is revealed to be just that. When confronted with contradictory information, it only tightens our grip on a self-defining self-delusion, especially when there’s a financial incentive to do so. And on a long enough timeline and with enough enablers nodding in agreement, our memories can be hammered into a shape that resembles the truth, or in this case, rock and roll lore.

Legacies have been built on far less.