“Mood board,” Kanye West tweeted last week. Between the disturbing tweets preceding it and the even more disturbing tweets yet to come, the post went mostly ignored. That’s fair; a regular maker of mood boards myself, I can freely admit that the habit is sort of cheesy, as well as the act of public sharing. It’s the kind of thing you expect from someone whose creative framework has an x-axis of “energy” and a y-axis of “vibe.”

One of the mood board’s elements was a pad of yellow notebook paper, on which was scribbled in half-dead Sharpie the word “ANDY” and a mouthless, unibrowed face presumed to be line-stepping performance artist Andy Kaufman. It was funny, in the way that people striking Serious Artiste poses over deeply silly art usually are. After a moment, the strangeness of the two books to its right sunk in: a lengthy hardcover accompaniment to an exhibition on the art of Joseph Beuys, and an oral history of Bliz-aard Ball Sale, a performance piece by the artist David Hammons. And if one thing has become certain in the past few weeks, it is this: Kanye West does not read books.

There is evidence, however, that suggests he at least skims them. An earlier tweet showed a page open to a photo of David Hammons’ Higher Goals, a 1986 sculpture installation in Brooklyn that fashioned ornate, towering basketball hoops out of telephone poles. You can see why West might be drawn to the image of that 35-foot hoop piercing the sky. It’s a real-life representation of limitlessness — specifically, black American limitlessness — and a fine complement to the manic self-optimization mindspray you’ll find on his Twitter between endorsements of MAGA mouthpieces and brutalist Pinterest-board fodder, screenshotted from Dropbox uncropped.

Mood board pic.twitter.com/huJXClpqtq

— KANYE WEST (@kanyewest) April 29, 2018

The titular performance of West’s mood board book, Bliz-aard Ball Sale, tells a different tale. In the 1983 piece, an anonymous-looking Hammons hawks tidy rows of snowballs to Manhattan passerbys; by the performance’s end, he’s sold them all. The piece was about art’s ephemeral nature, for sure, but it was also very much about art as scam — and artist, by extension, as fraud. It is probably pure coincidence that Ball Sale, of all Hammons’ decades of work, is the piece to which West gravitated, but a not-small part of me imagines it as fate.

And if it was coincidence that brought Joseph Beuys across West’s threshold, I imagine a fireworks display of resonance crackled upon learning the title of the late German artist’s most iconic piece: I Like America and America Likes Me. (Is that sentiment, wry as Beuys may have intended it, not precisely what West thinks he’s going for with his whole “Actually, wearing the hat will show people that we equal” thing?) Beuys was a bit of a trickster himself, though with a mystical bent; his dubious origin story involves the former WWII fighter pilot being rescued after a crash by a nomadic Tatar tribe, swaddling him in felt and fat — the genesis of his artistic life. By 1974’s I Like America, he was Germany’s most unusual and provocative living artist. He’d taken to calling his performances “social sculptures,” intended to enact positive change: “Only art is capable of dismantling the repressive effects of a senile social system that continues to totter along the deathline,” he wrote.

Disregarding all considerations of artistic quality and intellectual rigor for a moment, Beuys’ aim with I Like America was not totally dissimilar to West’s on the profoundly misguided “Ye vs. The People,” in which T.I. barely conceals his disdain through an unlistenable conversation about politics: the initiation of a national dialogue. On Beuys’ first visit to America, he arrived at a small SoHo gallery in an ambulance, carried in on a stretcher with his body wrapped in felt; there, he would spend the next three days cohabiting with a wild coyote he named Little John. “You could say that a reckoning has to be made with this coyote, and only then can this trauma be lifted,” he said, referring to American social divisions.

Beuys’ attempts to befriend the coyote were met with alternations of disinterest, hostility, and mild curiosity; in the end, the animal allowed him a small embrace. From all this, one could gather that the solution to the problem of America—the way to “disrupt” a divided nation, in Yeezy-friendly tech-speak—was direct communication. A less idealistic reading of the work might conclude that a coyote is not a symbol, but a coyote. And it is not your friend.

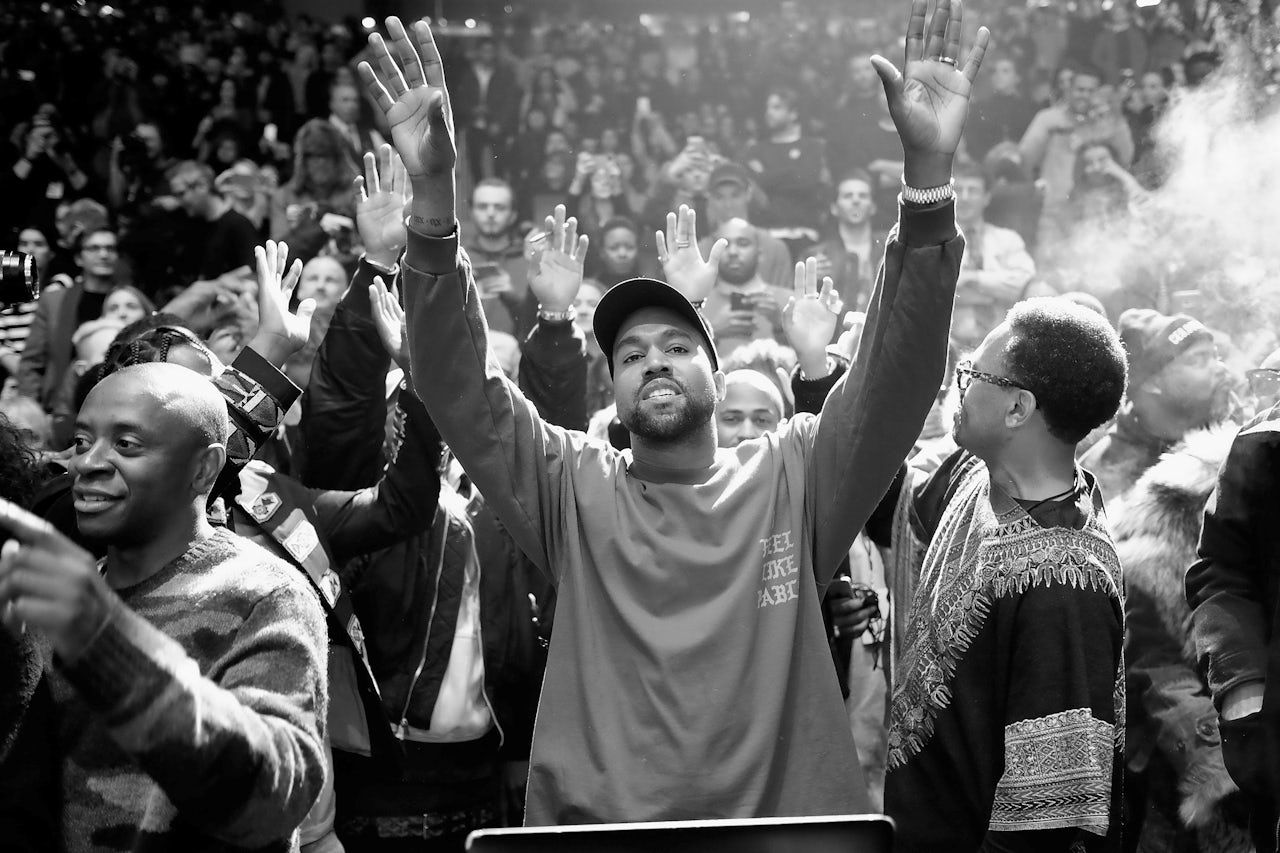

West has always been a conductor in not just the musical sense, but the electrical — one through whom currents run, for better and now, for worse.

Amidst one of the steepest, non-criminal falls from grace by a pop icon this century, I’ve developed a nauseous fascination with the aesthetics of Kanye West’s breakdown. In part, this is because the rest is too depressing to process: the most important musician of his time, spewing Fox News clichés and indulging the Dilbert guy, in a flailing attempt at iconoclasm. Days ago, a viral tweet series presented a conspiracy theory which argues, via Beuys, Hammons, Kaufman, and West’s friend Tremaine Emory, that the past weeks’ provocations have been part of a grand performance art piece. This may well be true, which changes very little about the profound recklessness of it all, to say nothing of the clumsiness of execution; most performance art, it should be noted, sucks ass.

Perhaps seeking some relief from it all, there is a sick comedy to be found in the greater mood board that is his Twitter: the your-mom-on-Facebook positivity memes; the inane dry-erase board brainstorms; the presumably unironic re-posts of New Yorker cartoons captioned with his tweets; the turd-like blobs of neutral-toned clay (“just great energy bro”). But beyond levity, West’s art and design proclivities seem to reveal more about his ideologies than I imagine even he realizes. For West has always been a conductor in not just the musical sense, but the electrical — one through whom currents run, for better and now, for worse.

“Axel Vervoordt the globe,” read one recent tweet, to which a frightening amount of replies suggest that real free thinkers are Team Flat Earth. Vervoordt — a Belgian designer with a comically designer-y name, whom West regularly visits in his 12th century castle called ‘s-Gravenwezel — designed Kanye and Kim’s Hidden Hills mansion. Pale-washed and empty-looking, most people responded affirmatively when West asked “Do this look like the sunken place” over a photo of its void of a hallway.

The day before his return to Twitter, The Hollywood Reporter published an interview between West and Vervoordt, which veered from expected fine art platitudes to outright delusion. The two agreed that keeping up with the news was for basics: “I almost never look at television because I like to have that open mind and feel things not with the influence,” said Vervoordt. “I'm a little bit scared that most news is too negative.” West went on to explain the deranged reasoning behind his “be here now, now be here” philosophy, which includes the rejection of photographs: “[Photography] takes you out of the now and transports you into the past or transports you into the future... People always wanna hear the history of something, which is important, but I think there's too much of an importance put on history.”

It was a Le Corbusier desk that brought West and Vervoordt together. Walking by Vervoordt’s booth at a Netherlands art fair in 2013, West was stopped in his tracks by the angular wooden structure. It may have been that encounter which inspired West to claim, in an interview months later, that a Corbusier lamp in his Paris loft was one of his greatest inspirations for Yeezus — his industrial album, from which “New Slaves” now looks a bit funny in the light. That lamp, made predominantly of concrete, ran West about $110,000(he appears to have been significantly overcharged). From our current vantage, Corbusier is almost inarguably the most significant architect of the 20th century — influence, of course, being artistically and morally neutral. He, too, had extreme and solipsistic ideas about the past, present, and future of architecture and moreover, society at large. To Corbusier, the past was a tyranny which should not be overcome, but destroyed and forgotten. As for the future: it began with his ideas, and his alone.

An early modernist pioneer, Le Corbusier’s preferred structures were harsh blocks of concrete as unadorned as possible. Directly challenging the neo-classicist styles that prevailed until the 21st century, Corbusier saw the impulse toward ornamentation — and beyond that, the pursuit of beauty—as not just aesthetically repugnant but morally perverse; his most influential book, 1924’s Towards a New Architecture, referred to a house as “a machine for living.” “We must create a mass-production state of mind,” he went on. “The only possible road is that of enthusiasm… that electric power source of the human factory.” Corbusier was as enamored with Henry Ford as West is with Steve Jobs, and his obsessions extended beyond architectural design and into urban planning, with a totalitarian zeal that crept openly toward fascism. In his quest to replace historic European cities with grim, uniform concrete grids, he imagined himself unprecedentedly bold, and anyone unconvinced of his genius as hopelessly conventional.

A Corbusier does not spring from thin air into being. Not only was global industrialization dramatically re-writing architecture’s possibilities, but the first World War had wreaked havoc on European cities, demanding immediate and efficient reconstruction. Beyond that, the elaborate bourgeois aesthetics of the 19th century provoked an opposite reaction; militant asceticism was a natural response. Why should art aspire to such meaningless standards as “beauty” when the postwar world had revealed itself to be ugly, chaotic, and brutal? If art’s duty was not to coddle but to speak truth, then the work of Corbusier and his devotees was not ugly, but honest.

It is telling — of not just West’s ideologies but those of society at large — that Corbusier’s aesthetic and social principles are perhaps more relevant than ever. In his 1925 book The Decorative Art of Today, he proclaimed that the future of design would be exclusively concerned with "objects which are perfectly useful, convenient, and have a true luxury which pleases our spirit by their elegance and the purity of their execution, and the efficiency of their services.” He went on: "The ideal is to go work in the superb office of a modern factory, rectangular and well-lit, painted in white Ripolin [a French paint brand]; where healthy activity and laborious optimism reign."

All this is eerily prescient of the design-as-life philosophies of West’s heroes Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, and beyond that, an all-too-familiar strain of bougie minimalism, currently beloved by the insanely wealthy and those who aspire to be. You know the look: luxuriously oppressive and eminently Instagram-friendly, the new #minimalism is potted palms against white walls, kitchens whose empty countertops are slabs of salvaged marble or concrete, a self-satisfied absence of the downer that is stuff. (There’s a famous photo of Jobs in the ‘80s, seated on the floor of his nearly-empty living room; it appears on Pinterest via a site called Lifehacker, with the caption “Do everything better.”) This ostentatious minimalism is consumerist at its core, stemming from the same cultural neuroses as does our current obsession with self-optimization, from Snapchat filters to “wellness” as industry to borderline-sociopathic proclamations that “the world is our office.” It is not just an aesthetic choice, but a moral imperative, within which lies the possibility of absolution.

If Le Corbusier was a symptom of his time just as much as he was a cause, so too is West. And clearly, he is not alone, in his inane and reprehensible politics nor in his rather dismal design inclinations. A recent series of tweets showed close-ups of some sort of Brutalist building, all hard lines and pock-marked concrete. The fascination is on-trend: “Brutalism Is Back,” declared a New York Times piece published exactly a month before the 2016 election. The mid-century architectural movement is named for Corbusier’s favorite ingredient, béton brut (raw concrete), and looks how it sounds: harsh, hulking, and wholly unconcerned with humanity. “There’s no question that Brutalism looks exceedingly cool,” the author writes. “But its deeper appeal is moral…. The brutality to which [Brutalist pioneers] referred had less to do with materials and more to do with honesty: an uncompromising desire to tell it like it is, architecturally speaking.” A soulless structure celebrated for its proud lack of soul; I do not think I need to spell it out.