The first of May, established in 1886 as International Workers’ Day, is one of the many public holidays Russia has inherited from the Soviet Union. Due to strict limitations on who can assemble in public spaces, where they can gather, and what ideas they can publicly express, it’s also the one afternoon a year when Russian activists are allowed to take placards onto the main streets. The march, an annual event in all major Russian cities, brings together an odd amalgam of protesters: environmentalists and animal rights supporters find themselves wedged between senior citizens toting Stalin nostalgia or ethnic nationalists raging against “parasites in the Kremlin.”

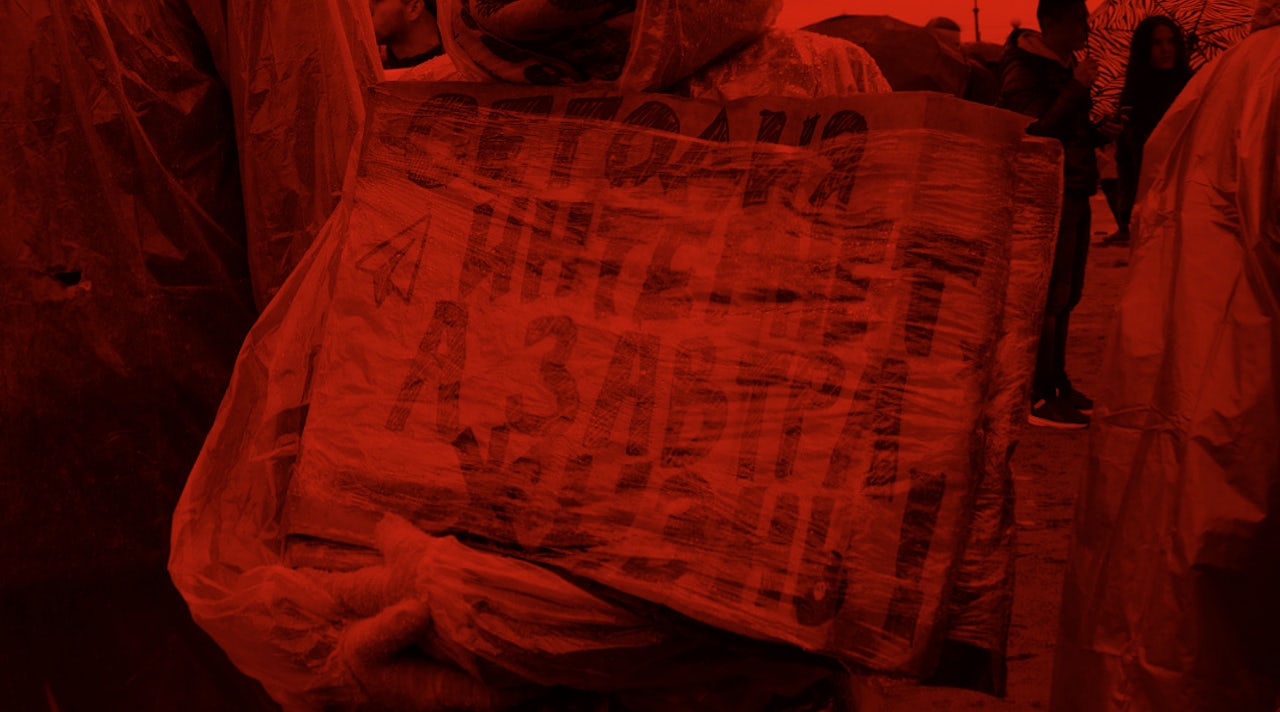

The point of the march is to come with a message and express it clearly — whatever that message may be. But increasingly over the past fifteen years, May Day has been home to a stranger kind of demonstration, with throngs of young people brandishing signs that simply don't make any sense. Some examples from yesterday’s march in Saint Petersburg: “Russian literature forbids marrying for love!”; “Papa, come home!”; “Freedom to victims of political depression!”; and “Bunnies will save the world!”

The signs belong to a “monstration,” an art happening that mimics protest with signs deliberately veering into the absurd. It isn’t only a May Day phenomenon: since the restrictive laws related to public gatherings make it difficult to advocate for particular causes year-round, demonstrating under the guise of performance art helps activists avoid the consequences that often result from large-scale political action, like last year’s mass arrests. Monstrations also offer a sharp critique of the Russian system — a mock protest meant to expose what many Russian young people believe to be a mock democracy, and challenge the Kremlin’s increasingly aggressive policing of public space.

Monstrations first appeared in 2004, organized by Siberian performance artist Artyom Loskutov, who later gained notoriety for his protest posters featuring icon-style depictions of Pussy Riot; they have since spread from Novosibirsk, Siberia’s cultural capital, to cities across Russia. The original gatherings touched on provincial corruption and the distribution of Siberian resources — but the monstrations in Moscow and Saint Petersburg have come to focus on issues universally affecting Russians, such as the corruption tainting Putin’s electoral wins or the controversial handover of public buildings, like the current transfer of St. Isaac’s Cathedral, to the Orthodox Church. But this Tuesday, in addition to drawing attention to the issues mentioned above, young people in the country’s two largest cities aimed their weaponized absurdity at a matter far more pressing to their demographic: online censorship.

The Putin administration has a history of internet control: in 2012, partly in response to protests following that year’s controversial presidential election, the Kremlin began assembling a list of blacklisted sites — ranging from LinkedIn to Pornhub to pages affiliated with the Jehovah’s Witnesses — and blocking access to them from national IP addresses. The controversial “gay propaganda law,” criminalizing the dissemination of LGBTQ information to minors, dates back to this period. VPNs were officially banned in 2017, and last month attempts were made to block Telegram, a secure messaging app that refuses to give the Kremlin access to users’ encrypted messages. This, for many, was the last straw.

Telegram was released in 2013 by developer Pavel Durov, the mind behind VK, Russia’s most popular social network, making him the closest thing Russia has to a Mark Zuckerberg. The app has drawn praise and controversy for security features attracting activists and terrorists alike. This is not Durov’s first major controversy: his refusal to remove content from VK connected to the Ukrainian crisis lead to his eventual removal from the social network’s leadership. This history has made Telegram an obvious target for the Putin administration, particularly in light of recent laws requiring major tech companies to store the data of Russian citizens on Russian territory — ostensibly in the name of national security.

Having refused to give over their encryption keys, Telegram stands in defiance of Kremlin policy. Young people, however, are standing with the messaging app: this May Day in Saint Petersburg, Moscow and other cities, separate contingents of protesters were organized by Durov himself and marched under official Telegram flags.

While the placards at monstrations typically avoid direct references to political events, many included Telegram’s logo, a paper airplane, in their design. One sign boasted a seemingly innocuous slogan, “We’re the sweets here!” — but the Russian word for “sweets” rhymes with “power,” and the board itself was decorated with paper airplanes. Other signs flirted with overt criticism of the new legislation — such as one that read “I didn’t need the internet anyway, thanks!” or another displaying an Orthodox-style icon of Durov holding an orb in the shape of the app’s logo.

The degree to which the Russian government interferes with freedom and democracy on the internet has increasingly become a source of major anxiety — not only to the minority of Russians who identify as liberal, but also internationally, as the U.S. inquiry into potential Russian interference in the 2016 American election unfolds. Like the blocking of Telegram, reports of Saint Petersburg’s “troll factory”. accused of spreading disinformation into the online echo chambers of American political discourse, point to yet another example of the Kremlin attempting to infiltrate and influence online space.

Given the magnitude of these concerns, parody might appear a trivial form of resistance. But faced with increasing restrictions on public expression, young Russians are using everything at their disposal to create and maintain an independent online space: show protests, ironic placards, encrypted apps. Protesters have only learned from last year’s mass arrests — they’re playing harder, smarter. And they’re showing no sign of stopping.