We’ve known for years that a person’s environment affects their body and health. On a basic level, the pathogens and viruses a person encounters, the drugs and antibiotics they take, as well as their diet, geographical location, exercise, or smoking habits all affect human health. This is important because people exposed to environmental risks—like air and water pollution or poor access to nutrition—are disproportionately more likely to be people of color.

Now, scientists have begun to figure this out on a genetic level. In other words, how the environment interacts with the human body and changes the way cells make decisions.

According to newly published research, Stanford scientists have the first concrete evidence that the environment accounts for 70 percent of how the immune system works and changes over time, which affects aging and how vulnerable people are to diseases.

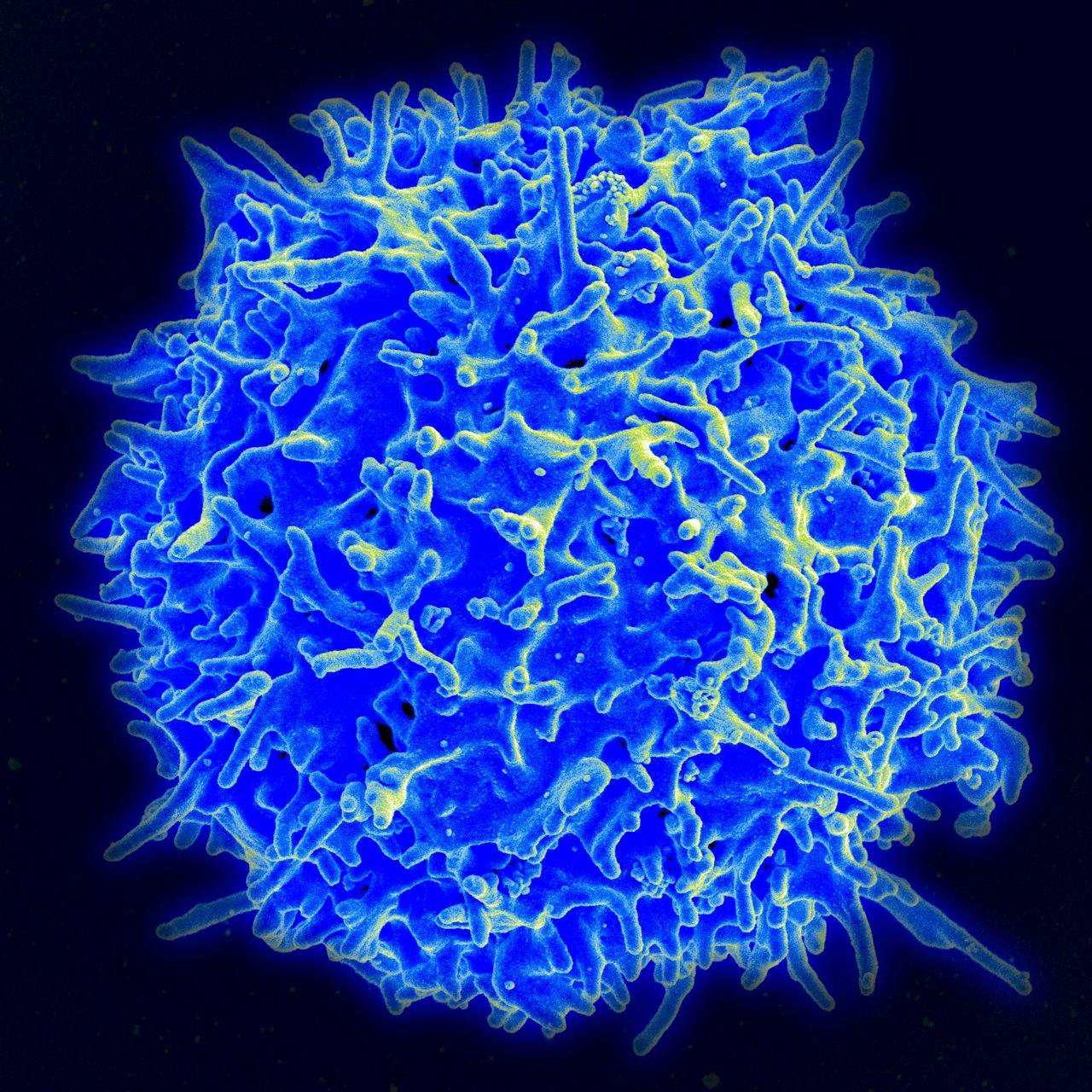

Specifically, this evidence has to do with “epigenetics”—or the way your body decides how stem cells become certain immune system cells. This decision-making process is linked to aging and chronic diseases like cancer, autoimmune diseases like lupus, arthritis, and sclerosis, diabetes, and pathogen-borne diseases like leprosy and dysentery.

According to an email from lead researcher Paul Utz, almost everything in an environment influences this epigenetic decision-making process.

“Everything you can think of—sleep, exercise, diet, alcohol, pollution, medications, toxins we breathe or eat, and certainly infections [have influence],” he said. “We are carefully testing many of these in the next series of experiments.”

With this concrete methodology and evidence, a whole new field of research possible. In the future, scientists could be able to make tangible links between a person’s lifestyle and environment and the diseases they’re vulnerable to—all on a cellular level.

“[In the future], we may better understand why a large subset of older individuals are more likely to develop autoimmune diseases, cancer, and infections,” Utz said. “Our results also may help predict why vaccine responses differ between different classes of subjects.”

The theory behind this genetic research was posed over 60 years ago by Conrad Waddington in 1957, but the tools and data analysis methods for uncovering evidence didn’t exist until now.

“Single-cell methods are needed to do this work, and only in the last three to five years has this been truly possible,” Utz said. “We actually knew very little about epigenetics and aging before this study, at least in the immune system.”

Lead researcher Purvesh Khatri told The Outline in a phone call that fine tuning this process brought about the 61-year delay in gathering evidence.

“In some sense, we knew the answer to our questions because they had been hypothesized in the field,” Khatri said. “But this was the first time we had data to answer those.”

We still don’t know exactly why these environmental changes happen, or who exactly is vulnerable. And researchers need to find these answers before anyone can be expected to use this to, say, cure cancer or reverse the effects of aging. However, both Purvesh and Khatri were optimistic about the future applications of their methods—the lives that could be saved, or the livelihoods that could be improved.

“An obvious question is, ‘Can we use this information to reverse the effects of aging on immunology?'” Khatri said. “The immunologic fountain of youth?” Maybe. This research is a decent starting point.