The stick of “Fortune Bubble” bubblegum I’ve purchased from Candy Rox, a vintage candy store in Bronxville, NY, is dusty pink, and hard enough to hurt my fingernail when I flick it. It takes seven good chomps to reach typical gum consistency, and tastes like pretty much any other stick of bubblegum, though maybe a little bit on the sweet side. The flavor lasted me about as long as a piece of Double Bubble, which feels like a good yardstick of gum longevity. (For those of you who don’t chew gum, that’s about five minutes.)

The gimmick that gives the candy its namesake is a fortune written on a piece of paper neatly folded around the stick beneath the wrapper. I unwrap the one I’ve selected, which reads: “Something you lost will soon turn up.” There are actually two fortunes on the piece I’ve chosen. Partially cut off, the other appears to read, “Smiling often [will m]ake you look [and f]eel younger.”

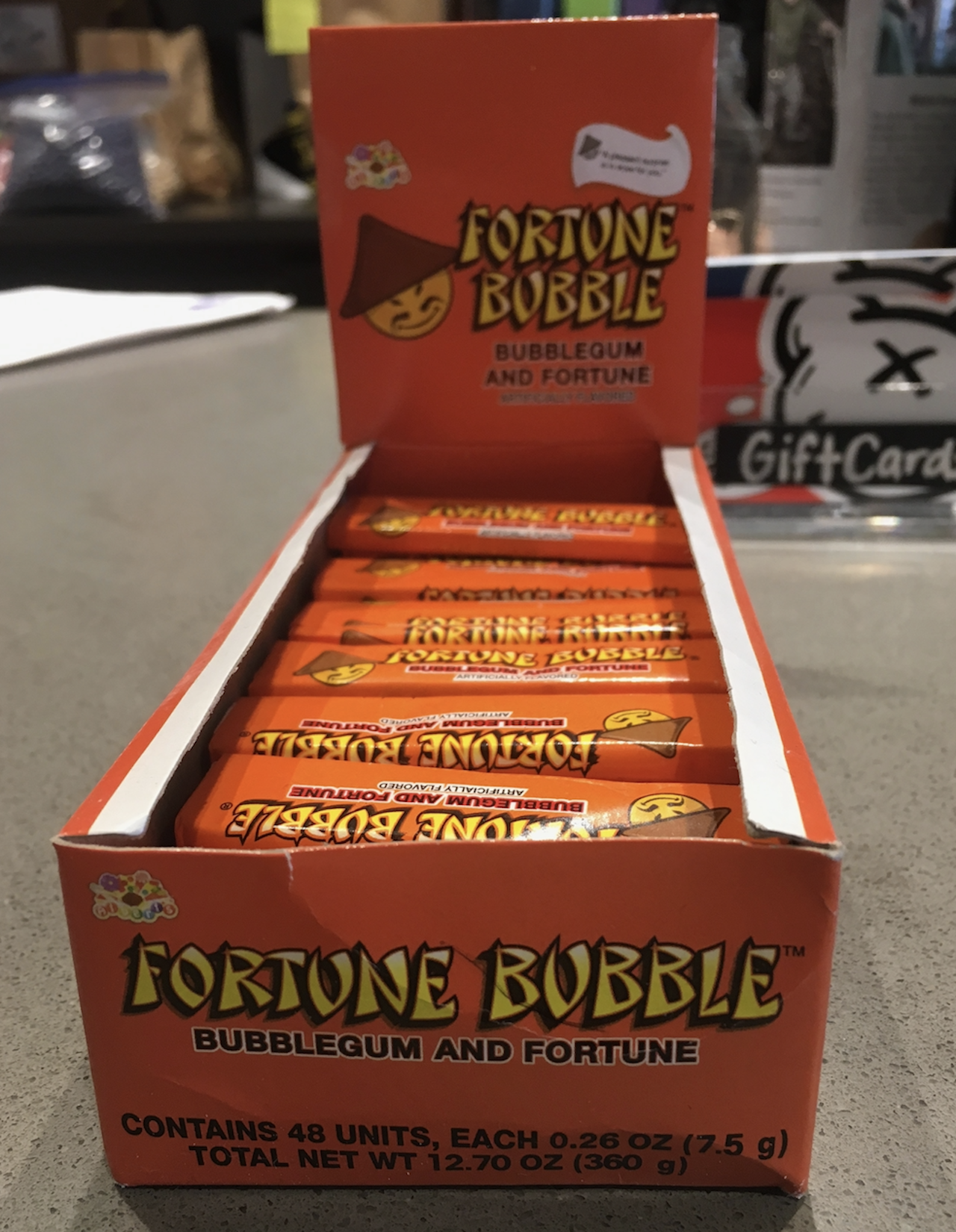

This is all fine, but something about this product had caught my eye: its packaging. The orange wrapper features its name in a “chopstick” type lettering alongside a crudely drawn cartoon character. The caricature has a yellow face, eyes represented as slanted lines, a conical “farmer” hat, and a Fu Manchu mustache.

“What the hell is this?” I remember asking aloud the first time I saw it at the shop, before taking a quick picture on my phone. The sheer absurdity of it stuck with me for days. I later returned to the store to purchase two packs for research, but also to verify I hadn’t somehow stepped through a hole in the space time continuum and landed somewhere back in the mid twentieth-century.

Listen to a conversation with Allee Manning and more information about Fortune Bubble on The Outline World Dispatch.

Pocket Casts / Overcast / Stitcher / TuneIn / Alexa / Anchor / 60 dB / RadioPublic / RSS / “OK Google, play news from The Outline.”

Fortune Bubble is a product of R.L. Albert & Son, Inc., a confectionary company based in Stamford, CT. According to its website, the company has been in business since 1916, operating under the name R.L. Albert, Inc. until the 1930s.

Fortune Bubble isn’t the only example of questionable marketing that can be found in the company’s history. According to the Candy Wrapper Museum, an online collection of vintage candy memorabilia and images collected by candy historian Darlene Lacey, R.L. Albert released a candy called the “Hippy Sippy” back in 1968. The confection came in a plastic syringe and came with pins featuring slogans like “I’ll Try Anything” which allegedly led to outcry and its eventual discontinuation. But Fortune Bubble does appear to be R.L. Albert & Son’s only noted foray into marketing candy in a way that evokes race, a common thread throughout U.S. confectionery history.

According to April Merleaux, author of Sugar and Civilization, a book on the cultural politics of sweets, the “rise of big candy” in the 1920s was accompanied by a market embroiled in racial politics. In 2015, she told NPR about the “Jim Crow candy hierarchy,” as she called it, referring to the racially-coded candy advertisements and marketing of that time period. Higher-end, expensive candy was intended for white women and the middle class; cheap candy was made for and marketed to African-American and immigrant children.

This dichotomy could also be seen in the hiring of workers at candy factories. As Krishnendu Ray, a sociologist and professor of food studies at New York University told The Outline in an e-mail, “entrepreneurship rates among whites [in this era] were often higher than among others because of fewer racial barriers.” This, combined with candy makers being “immersed in local communities of prejudice often unselfconsciously,” resulted in products being marketed in racially insensitive ways as the mass production of food led companies to adapt characters and personas for their brands to give off a more personal, homemade feel (like Aunt Jemima, the Green Giant, and the Rice Krispies elves).

Throughout the years, there have been a slew of race-related candy controversies. Some are pretty recent. In the early 2000s, the Canadian candy company Sloche released packaging that featured an illustration of an angry-looking black man with a gold tooth and giant spider made to resemble dreadlocks atop his head. They later pulled the product and donated $18,000 to a mentorship organization. A “blackface” licorice candy sold by Haribo in Germany was pulled off shelves amid complaints in 2014.

Fortune Bubble isn’t the first candy to play on Asian tropes and stereotypes, either. In the mid-1960s, Pillsbury released a “Funny Face” drink mix flavor called “Chinese Cherry” featuring a personified fruit character with slanted eyes and buck teeth. There was also a nearly unbelievable item called “Rots O’ Ruck Candee Yen Toy,” which features two bucktoothed, conical hat-wearing characters lighting dynamite on one package. Another features an equally stereotypical East Asian man about to have a safe dropped on his head.

“Once these kinds of images — slanted eyes, conical hats, deception, Fu Manchu — begin to circulate, people think that is the way you should represent Asians or Asian Americans and begin to make sort of a rationale for it.”

These products were created during a time period of notable racial tension. Passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments in 1965 declared that discrimination against immigrants based on race and nationality was unconstitutional, leading to a new wave of Asian emigration. Amid this population shift, the Vietnam War stoked anti-Asian sentiment among white Americans, playing on culturally-entrenched racism that was codified into society through century-old racist legislation like the Chinese Exclusion Act. Asian immigration rates continued to rise dramatically for the next two decades; the number of Asian immigrants gew by 308 percent in the 1970s, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Between 1980 and 1988, the overall Asian population of the United States increased by 70 percent.

“Periods of explicit visual racism and racist energy pop up on a regular basis,” said Jack Tchen, co-author of Yellow Peril! An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear. Yellow peril refers to the xenophobic colonialist attitudes that have portrayed the culture and peoples of Asia as an enemy that threatens Western society. “This kind of ‘racial humor’ often coincides with yellow peril violence. It’s also a release valve from virulent hatred racism, which oftentimes results in violence, or is sometimes a consequence of violence and a war.”

It’s difficult to confirm when Fortune Bubble was first released, but discussions online and descriptions from retailers selling it indicate the gum was likely created in the 1980s, and discontinued at some point in the 1990s. When I reached out to Robert Katz, the CEO of R.L. Albert & Son, Inc. to discuss the gum’s history, and got in touch after several inquiries, I was told over the phone that the company does not speak with journalists and that he wasn’t interested in discussing any aspect of their products.

You can easily understand the context in which this candy was originally produced: Racial stereotypes have long been amusing to the historically white titans of industry. (For reference, John Hughes’ much beloved Sixteen Candles, which features the wildly inappropriate Long Duk Dong character, was released in 1986.) But it was much harder to understand why anyone might think it was a good idea to bring it back with the original packaging — how nobody at the company had seen the proposed designs and waved a red flag.

Information on when Fortune Bubble was re-released is hard to come by online, and company employees wouldn’t answer my inquiries. Reviews of the candy being sold on Amazon by a seller called R.L. Albert & Son first began appearing in 2015. Kent Ono, a communications professor at the University of Utah and co-author of Asian Americans and the Media, said that these representations persist in part because Asian-Americans have not historically had the power to produce self-representations in large numbers. This has led to a ritual caricature coming out of an imagined nation.

“Once these kinds of images — slanted eyes, conical hats, deception, Fu Manchu — begin to circulate, people think that is the way you should represent Asians or Asian Americans and begin to make sort of a rationale for it,” he said. “One of the rationales being it’s comical it’s funny it’s light-hearted, it’s cartoonish, and therefore should not be taken seriously; that anyone with a sense of humor can understand that it’s tongue-in-cheek. We’re supposed to smile and accept this. And, of course for Asian and Asian American consumers… it’s a colossal failure. The vast majority will find it repulsive and abhorrent.”

So who is actually buying it?

“There’s a certain customer, probably retired with some time on their hands…[for whom candy is] like a time capsule that can take them back to their childhood,” said Beth Kimmerle, a candy historian who also works in confectionary product development. She agreed that Fortune Bubble doesn’t make sense in today’s world, but stressed that this isn’t likely of concern to those buying it. They’re just looking to wade into the fountain of youth. (Indeed, most of the comments on the gum’s Amazon page are from customers referring to their nostalgic memories.)

“Candy is one of the few products that can do this,” she said. “It has the smell, the taste, the packaging, the sound [of unwrapping]. It’s this whole sensory experience that can take people back to being at a dime-store with their grandmother and buying this candy. It’s a transporter.”

For these customers, a lack of political correctness isn’t going to stop them from seeking out this powerfully nostalgic product. Maybe, Kimmerle added, the people running this family-owned candy company have their own personal associations with it.

When I first came upon the candy while perusing the store with my mother, who is half-Korean, I asked her if she could believe the absurdity. She shrugged before wandering away; it seemed to perturb me more than it did her. When I later pressed her, she told me that having grown up attending schools in the Bronx and lower Westchester, NY, composed almost entirely of white students in the 1970s, she and her siblings were regularly ridiculed and harassed for their race and appearance. To her, some cartoon on a stick of gum didn’t feel quite as personal. Instead, talking about it evoked the other bitter memories of her childhood — an era where stereotypes like this wrapper were wholly acceptable, even as they seemed totally innocent to many others.

Beyond making my mom sad, Tchen told me there are bigger picture issues at play, noting President Trump’s declaring a trade war with China plus the evoking of the Muslim ban. "These racial codes have pervaded our lifetimes,” he said. “The fear is always that as long as these things are not combatted actively then representations of [Asian peoples] can easily be manipulated and be part of the way yellow peril operates in the political culture.”

R.L. Albert & Sons was a dead end, and it was frustrating to realize I still had no idea how exactly this little stick of gum ended up in my possession. My first e-mail to the owner of the candy store where I first discovered Fortune Bubble — I was hoping to talk about the gum’s popularity — went unanswered. A couple days later, I called the store to see if they were still selling the product.

“Yeah, we do,” she answered.

“Is it, like, popular? Do people purchase it often?” I asked.

“Um, yes. People that used to eat it…” she trailed off, before being seemingly cut off by a coworker. After a nervous chuckle from the other end of the line, the phone went dead.

Within hours, I received a response in my inbox from the store’s owner: “Please understand, it is our policy not to comment on merchandise and our suppliers. Best of luck with your article.”

Correction: A previous version of this article referred to the wrong John Hughes movie.