Plastic is ubiquitous in nearly every product that people consume, and only recently have scientists realized that the microscopic beads, fibers, and strands that these bottles, bags, soaps, and clothes shed, or what are known as microplastics, are also ubiquitous.

Microplastics aren’t just in The Great Pacific Garbage Patch. They’re scattered throughout the ocean, distributed by the churning water to even places that humans have never physically visited. In fact, they’re in such large quantities that the fossil record of the ocean floor is building up a new layer of plastic.

For seafloor-swelling life forms like mussels as well as fish, this means that microplastic contamination unavoidable, and it will end up in the human food supply. In the case of sea life, when water is infested with microplastics laden with toxic chemicals, research shows the development of sea life is impaired and their ability to function is reduced.

According to a study published yesterday in Science Advances, the fact that microplastics end up in the food supply also means they end up in compost created from that food. Composting has been widely regarded as our best hope to replace artificial fertilizer, which sets off a series of events that makes climate change worse, particularly for the 815 million people on the planet who are already food-insecure.

It doesn’t matter how people compost their food—with or without oxygen, or with heat or without heat. Every method releases microplastics into to the environment, and there’s no indication that they’re in any rush to degrade.

“A recent study… showed no appreciable degradation of [microplastics] over the investigation period of 500 days,” the Science Advances study reads. “It is therefore likely that these particles, once released, will accumulate in nature over time.”

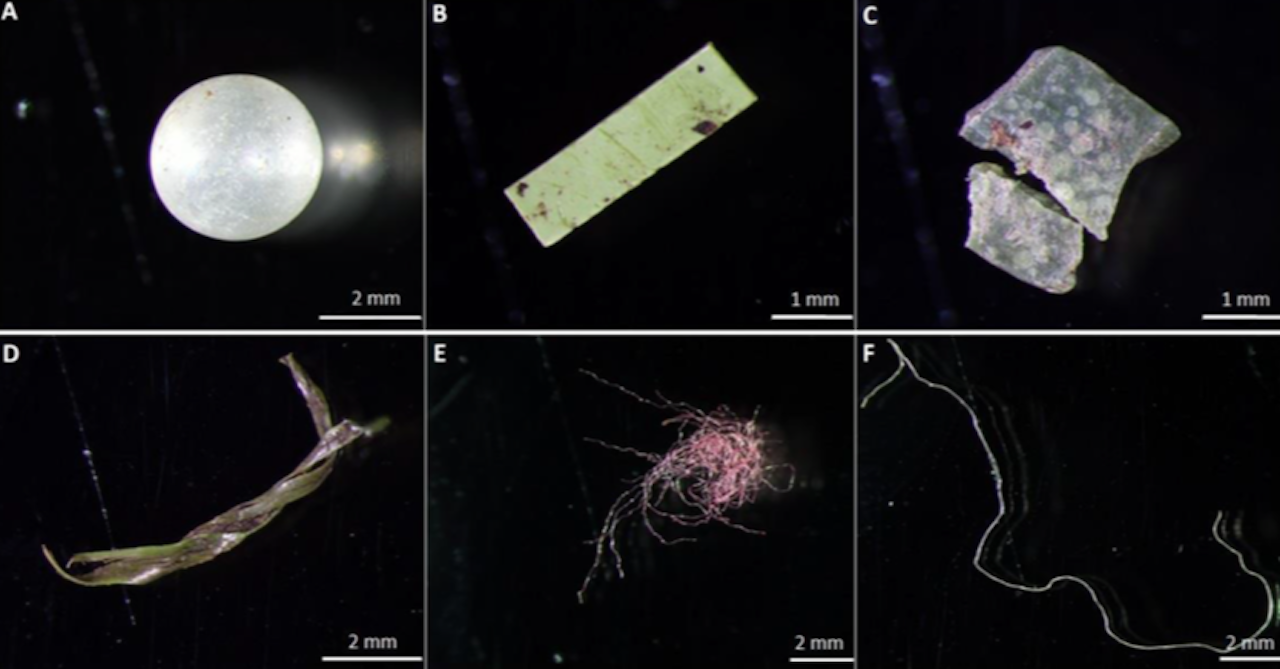

The study also discounted microplastics smaller than one millimeter in length, citing uncertainty about the sophistication of the tools they use to measure particles that small. This means that the study likely underestimates the amount of microplastics found in the compost samples they studied.

The 8 billion people on this planet create a pretty massive demand for food, and farms are incentivized to use artificial fertilizer in extremely large quantities in order to keep up. In the long term, the soil becomes much less productive, meaning that farmers have to constantly replant their crops—a practice which releases carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas (agriculture in general contributes over a third of all emissions driving climate change).

Artificial fertilizer leaks toxic amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus into the soil, which eventually reaches rivers, estuaries, and oceans. This changes the chemical balance in the water and can create dead zones, or areas where fish suffocate because there’s not enough oxygen.

Compost is an attractive alternative to artificial fertilizer, but when researchers factor in the presence of microplastics, it becomes a less attractive solution. According to a literature review by Chelsea Rochman, an ecologist at the University of Toronto, and published in Science today, there’s no evidence these microplastics can get into the food and crops that grow from this soil, but the review notes that they may hurt the microbes that live in the soil, which in turn, would hurt the productivity of the crops.

“There are some blind spots in our understanding of the impact of microplastics,” Rochman wrote in her review that since microplastic research started to proliferate in 2004, scientists have mostly focused on the ocean. But microplastics are ending up everywhere else too.

“The current evidence suggests that microplastic contamination is as ubiquitous on land and in freshwater as in the marine environment,” Rochman wrote. “But little is known about its fate and effects in freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems.”

In her literature review, Rochman also noted that even if microplastics don’t have a direct toxic effect on human beings, they affect the sensitive water and soil-based ecosystems that humans depend on.

The toxic effects of microplastics on sea life don’t happen in a vacuum, but scientists have only started to explore the issue on an ecosystem scale. Rochman notes that in the case of freshwater life, there’s even less knowledge about ecosystem-level effects.

“Even though the oceans cover more than 70 percent of our planet, the biodiversity in freshwater and terrestrial systems combined is more than five times greater than in the ocean,” Rochman wrote.”

Climate change is already altering the chemistry of the ocean and contributing to mass fish die-offs, and ecosystems are struggling to survive. Since much of the world’s most economically vulnerable depend on fish for food and jobs, microplastics represent yet another risk to these populations.