It’s a familiar story: a weather app says to expect several inches of snow, but there’s actually just tepid rain, or nothing at all. Your first instinct is to blame local meteorologists for blowing it. That’s where the weather app gets its data from, right?

As it turns out, weather apps rarely even consult with meteorologists, and there are no rules in place regulating how stock weather apps, or the hundreds of self-described “weather” apps on the iOS App Store and Google Play, create forecasts. Basically, there’s no reliable way for users to get vetted weather information on their phones. Minute-to-minute weather forecasts are fake, say meteorologists, and they would like the world to know they have nothing to do with them, thank you very much.

Weather apps often rely on forecast algorithms alone, without the supervision of human meteorologists. According to Birmingham-based meteorologist James Spann, less human oversight makes forecasts more fallible. But this doesn’t stop actual human meteorologists from shouldering the blame when the apps get it wrong.

“People just assume that the usual line—‘these guys are wrong and 90 percent of the time and they still get paid,'” Spann said. “You just see this illusion of the [meteorological] science not being where it is. But if you take a product that's actually vetted and prepared by a professional meteorologist, it is going to be right a whole lot more times than it's going to be wrong.”

Many people never download a weather app at all, and instead rely on the stock apps of their iPhones and Androids. But these apps aren’t designed to do much more than spit out a computer-modeled forecast. Eric Floehr, founder of forecast analysis firm Forecast Watch, said these forecasts are bought as APIs from private forecasting firms, such as The Weather Company.

“Apple doesn’t make forecasts. Microsoft doesn’t make forecasts generally. They’re purchasing forecasts from one of these other providers,” he said. “Some forecast apps may get forecasts from a number of different providers.”

Not all companies are transparent about which forecasting services they use. While iPhones show "The Weather Channel" logo in the bottom corner of the app, it’s unclear if that’s the only API forecasting service Apple uses. Apple and Google did not respond to requests for comment.

So how do these weather companies create forecasts? In a phone call, AccuWeather vice president Jonathan (Jon) Porter said that Accuweather has on-staff meteorologists to reconcile weather data provided by twenty-five global governments—such as the United States, China, and Japan—with Accuweather’s modeling system, which accounts for the modeling biases of the countries from which they attain the data.

“Our [computer] system is able to ingest all of that information and automatically generate forecasts for any point on the planet,” Porter said. “We have over 125 expert meteorologists at Accuweather, and they’re able to hone in on specific impacts and enhance those forecasts even further.”

Generally speaking, this makes information about mild weather reliable and accessible on a global scale. However, it’s not a perfect service. The attention of these on-staff meteorologists is typically dedicated to weather events that are harder for computers to predict—such as rain storms, snow storms, and hurricanes. Thousands of these events occur around the world each day, and there isn’t the human infrastructure to provide individual attention to each event.

This means that a large portion of weather forecasts on apps end up being dictated by computer models, which can’t explain their reasons for making a forecast. Users have no way of knowing whether their local forecast has been reviewed by a human.

And of course, not all forecasts are equal. According to 2016 research from Forecast Watch, the best forecast services for one to three day forecasts are Weather Underground, The Weather Channel (which owns Weather Underground), and Accuweather, which are accurate about 75 percent of the time. In comparison, Dark Sky and World Weather Online, the eighth and ninth most accurate forecasting services, are accurate 64 to 67 percent of the time.

Of course, that’s not to say that user expectations of weather apps are completely reasonable.

Eric Floehr of Forecast Watch noted that weather apps are simply meeting the appetite that smartphones naturally create for immediate information. In the case of weather apps, this may not be a good thing for users.

“Forecasts used to be a couple days ahead,” Floehr said. “Now, you’re planning your outing for the weekend on Monday. And you’re [also] just looking an hour out, a minute out. So it’s changing the horizons. The horizons of forecasts are broadening.”

This demand has led to the emergence of minute-by-minute forecasts by services such as Accuweather and DarkSky. Porter said in a phone call that Accuweather has information about neighborhoods on the “block by block level” that makes these forecasts possible. DarkSky did not respond to a request for comment.

However, Spann called these minute-by-minute services a “total scam.”

“They can't do that!��� Spann said. “That's beyond the limit of this science.”

Floehr noted that minute-by-minute forecasts would need hyper-specific information about the weather in an area. However, the infrastructure needed to reliably gather this type of information simply doesn’t exist.

Spann said it’s also important for people to know what goes into a forecast. Meteorologists take observations from weather balloons, radios, satellites, radars, and observations from the ground. Then, they factor in their interpretations of various computer models, which all make different assumptions about weather patterns.

Only after all of this information is analyzed does a forecast reach the public. But in the case of weather apps, where most forecasts depend upon a computer model, almost all of this critical analysis is skipped.

Extreme storms, hurricanes, and blizzards are hard to predict for humans and computers. So can weather apps help warn users about storms that have been forecast by computers and human meteorologists? Not always.

Part of the problem is that when these apps get everyday weather wrong, people’s trust in weather science is undermined. For those in areas that rely on traditional warnings for extreme weather, such as a sirens, that can be dangerous. Not having access to a second source of emergency information, such as a trustworthy warning app, can mean the difference between having time to take shelter from a life-threatening storm or not.

The National Weather Service (NWS) issues free mobile alerts in the case of extreme weather events and communicates weather advisories to private weather companies such as The Weather Company and Accuweather.

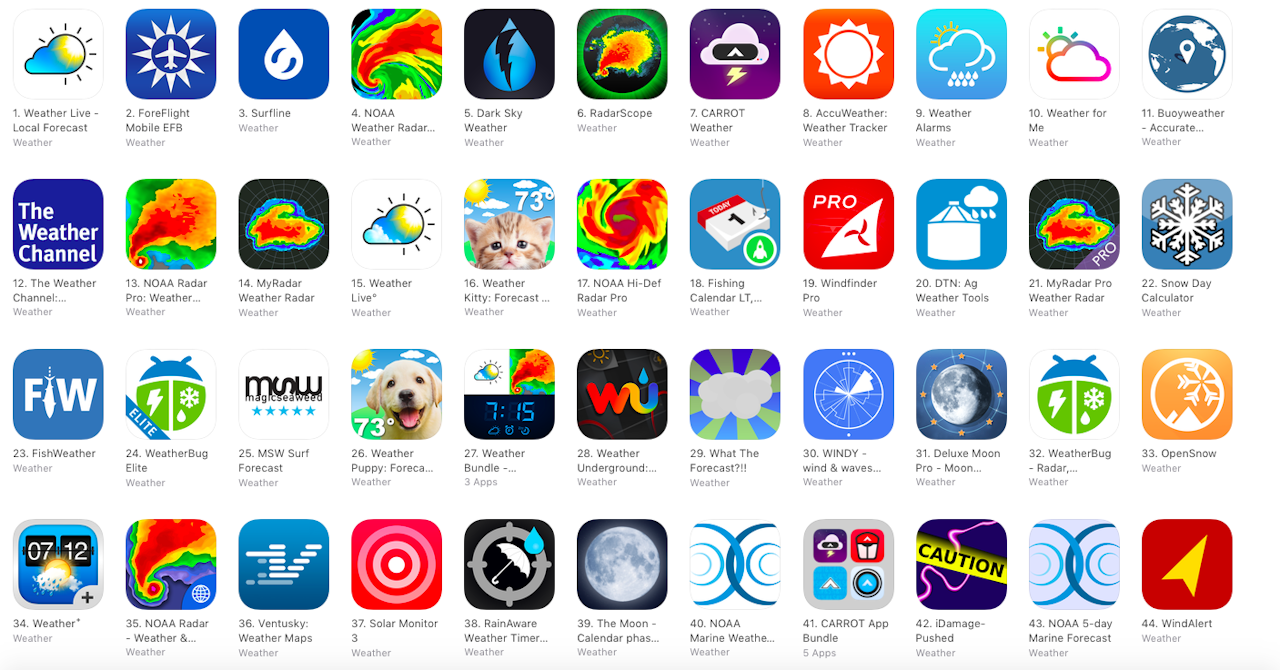

However, neither the NWS nor its parent National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have a free app that provides access to government-funded weather data. Apps such as “NOAA Weather” suggest an affiliation with NOAA, but that app is actually owned by app developer Apalon.

In an email from Susan Buchanan, a spokesperson for the National Weather Service, she said that there is no need for the NWS or NOAA to develop a weather or warning app due to the success of private meteorological firms.

It’s also worth noting that the NWS suffered extreme funding cuts this past fiscal year. And according to Spann, the few apps that are designed to handle emergency messages may have a cost barrier. For instance, Weather Radio, which Spann recommends for tornado warnings, costs $4.99 in the iOS App Store.

“[Meteorologists] have learned that we do a very poor job of reaching low income people with our products and services,” Spann said. “And when it comes to tornado warnings, I've got to reach every demographic across the board.”

People have never had more access to weather information, and weather apps can inform life-saving decisions, like seeking shelter or getting to higher ground. But according to Spann, until weather apps are reliably vetted and accurate, local meteorologists will continue to shoulder the blame when these apps fail, and in extreme cases, people may lose their lives.

“Seven years ago, we had a generational type tornado outbreak where in my state and in one day, 252 people died,” Spann said. “The statistical science could not have been better. But we learned that the physical science is not enough. We have to be good at social science, and part of social science is the communication process to get those warnings out."