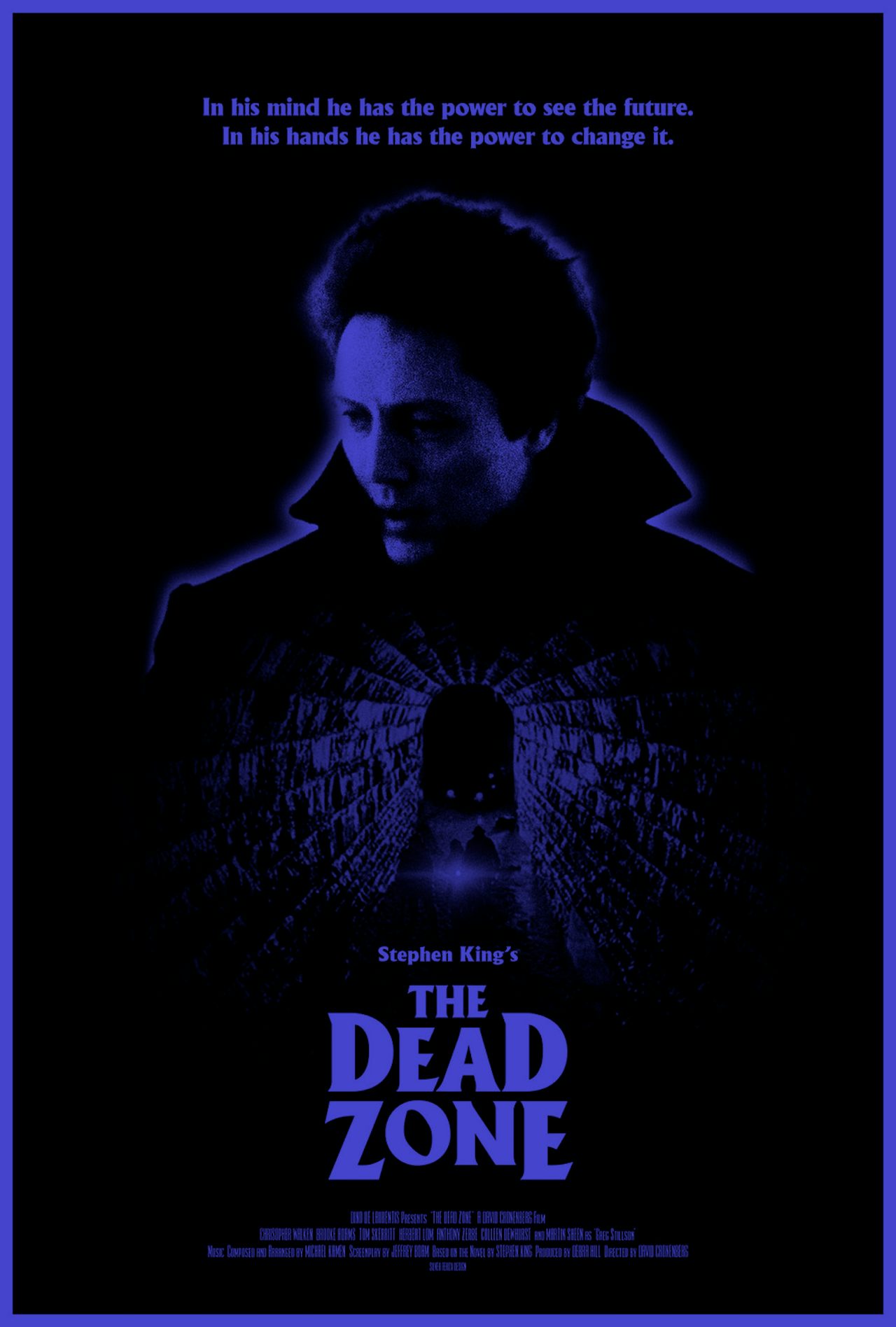

In Stephen King’s how-to-guide and memoir, On Writing, the author traces the genesis of his 1979 novel The Dead Zone back to two questions: “Can a political assassin ever be right? And can you make him the protagonist of a novel?” The answer, of course, is that if you lock Stephen King in a room he’ll write a book about anything.

As a novel, The Dead Zone is fine. Sandbagged by exposition and subplots, it’s a memorable concept if nothing else. However, as a movie — specifically, as a movie directed by David Cronenberg and starring Christopher Walken — The Dead Zone shines. Though it was released in 1983, it seems to offer a strange tonic for keeping one’s head during Trumpism. It takes seriously the burdens of skepticism. It examines the emotional purgatory of “outsiders” who really do know things that others don’t but still might be crazy. Through Cronenberg’s direction and Walken’s performance, the real forgotten man isn’t a ruddy white guy squealing about immigration and steel tariffs, it’s a wounded Cassandra who refuses the most American of emotions — optimism.

Stephen King has an absurd hit rate when it comes to adaptations of his books — this Wikipedia page says it all — because he excels at starting with dark nostalgia and mixing it with either an ancient supernatural evil or a Twilight Zone-ish tweak on reality. Even his lesser books still ripple with set pieces, productively broad characters, and primary color emotions: useful things for commercial novels and manna for Hollywood. Here, he takes an everydude in an idyllic Maine town and immediately plunges him into hell, only to curse him with the ability to see how people are going to die whenever he touches their hand.

By the time Cronenberg got a crack at a King book, he’d already made half a dozen films cementing his reputation as the Hieronymus Bosch of bodily decay. His early works came across as half penny dreadfuls, half social critiques, and unfolded like visceral little King stories themselves. Scanners is about government-raised psychics who can literally make people’s heads explode; Videodrome concerns a mysterious snuff film satellite TV channel that drives its viewers insane. If there was an ideal director to take King’s novel and give it scary bug-eyes on the silver screen, it was him.

The set-up, in brief: Christopher Walken, at his most young and moon-faced, plays Johnny Smith, a small-town New England school teacher. We open with six minutes of him reciting Poe to rapt kids, rocking a bowl cut, and chastely dating his colleague. Then he gets into a car accident, falls into a five-year coma, and wakes up in a David Cronenberg movie. He’s bedridden, stuck in a clinic run by an eastern European doctor. His old girlfriend is married and has a child. His mom won’t stop screaming at God, and also he has nightmarish visions when he touches people’s hands.

In the transition from first act to second, Walken sizzles, and his eyes begin to ping with a heady mixture of reluctance, rage, and grief. Like a lot of excellent portrayals of mania, Walken seems to be acting in his own personal diving bell, wincing at forces other characters can’t even feel. When he first discovers his power-slash-curse, he sees his nurse’s daughter cowering in the corner of her burning bedroom. He lurches up in bed to announce this, then Cronenberg places him in the child’s bed so he can lurch up and announce it again. But he’s right. The nurse runs out of the ward and gets home to see firefighters rescuing her child.

Visually, Cronenberg lets all degrade: the bright whites of the opening minutes become sludgy. Queasy interiors look like they’ve been lit with bare bulbs. Filmed in Ontario during a winter so surreally cold that crew members got windburn and an extra collapsed, the exterior shots pulse with chill and decay.

The film rests on two conceits. First, Johnny’s visions are absolutely correct. There’s no fog, no unreliability. Second, he hates his power. When a reporter mocks him at a press conference, and challenges Johnny to read him, Walken grabs his hand and tells him — sotto voce — a terrible truth about the reporter’s past. No cut away to a revealing flashback. No sound effect. Just Walken and the reporter making increasingly desperate eye contact, then the reporter melting down and calling Walken’s Johnny a “fucking freak.”

At the end of the first two acts, Johnny has become Job. Wounded during a confrontation with a serial killer (long story) and bereft of family and friends, Johnny lives on the literal edge of town. He tutors struggling kids; his bowl cut has become a layered post-punk masterpiece. When the doctor that saved his life visits and asks Johnny about the tower of mail from people who want his help, Johnny replies: “They all want the same things: reassurance, help, love. Things I can’t give them.”

Enter the movie’s third act, and its gloomy exigency. An unmoored, toxically charismatic local politician, Greg Stillson, is running for senate. Played by Martin Sheen in a wild photonegative of President/Saint Bartlett from The West Wing, Stillson is one tank parade away from Pinochet. He shrieks about weakness infecting the national consciousness and threatens small town newspapers. He does push-ups on TV then puts on a hard hat. The average white citizens in the broke old towns dig him, the elites complain and dither, et cetera. In On Writing, King writes that he saw some Stillson in Jesse Ventura’s ascent to the governorship of Minnesota. More recently, he’s been comparing Stillson to, well, you can guess who.

At a rally, Johnny shakes hands with Stillson. Johnny gets a final vision: Stillson will eventually become President and start a nuclear world war. He’s going to kill us all. It’s going to happen.

Johnny asks his doctor, the man who has protected him since his accident, a Polish emerge who survived the Third Reich — Johnny reads him early in the film — if he could go back in time and kill young Hitler, would he? The doctor’s response and Johnny’s decision supplies the climax. I won’t spoil it here.

In the David Cronenberg adaptation of the Stephen King novel, it’s seductive to try to act like an oracle, claiming we have all the pieces put together as we note each venal and cardinal offense of the current administration. Plenty do. The tweets and articles are maddening to read. They have to be maddening to write. Momentarily edifying as it may be to point toward the worst timeline, it’s a mug’s game. We are not Johnny Smith, and ultimately, we have no idea how any government or leader will act. All we can do is wait and see.

The Dead Zone offers the dark fantasy of rendering paranoia as pure gospel. Johnny doesn’t even get the satisfaction of an explanation as to why things are this way, just the grim knowledge that he’s right and that everyone except the audience thinks he’s nuts. That Walken’s and Sheen’s eyes both shimmer with the same madness in the final minutes feels right. A quarter-decade later, it’s a clarifying image for confusing times: the zealot and the would-be-dictator, closer in soul than either can ever know.