Books — good ones, anyway — are conduits for a pleasant sort of meditation, one that places you inside some far-off brain instead of your own. They bring you to a place where you can watch, uninterrupted and unnoticed, while a different world carries on like normal. They sneak you in, give you popcorn, and pat your head and say, “Stay as long as you’d like.”

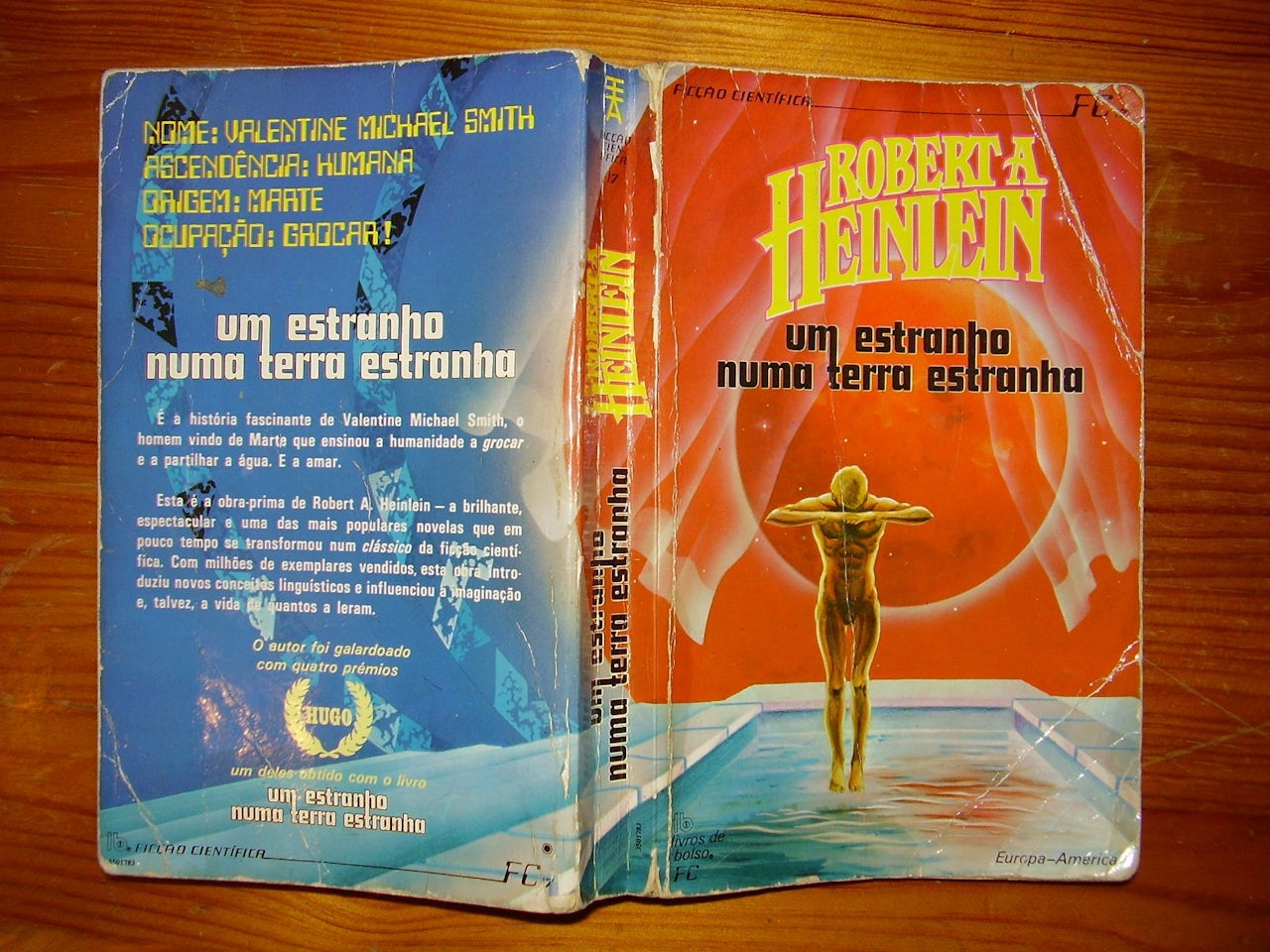

It’s jarring when a line comes along to knock you out of that stupor. It happened recently, while I was reading Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, the Jungle-Book-but-on-Mars classic originally published in 1961. The book tells the tale of Valentine Michael Smith—a human born on Mars and raised by Martians — brought back to live on a future Earth as a young man.

Jill, a nurse who initially assumes responsibility for Mike’s care, speaks the line: “Nine times out of ten, if a girl gets raped, it’s partly her fault.” By this point in the narrative, she has become Mike’s lover, and will soon become a partner in his cultish religion-cum-philosophy. The two are discussing, albeit vaguely, what will become a prominent part of the book: non-monogamy.

“I wouldn’t turn Duke down—and I would enjoy it, too! What do you think of that, darling?”

“I grok a goodness,” Mike said seriously.

(”Grok,” now part of our human vocabulary, originated from Heinlein’s novel. It’s a Martian concept that suggests an innate, holistic understanding or connection to something.)

“Hmm… my gallant Martian, there are times when human females appreciate a semblance of jealousy—but I don’t think there is any chance that you will ever grok ‘jealousy.’ Darling, what would you grok if one of those marks made a pass at me?”

(“Marks” is a disparaging term for members of the general public; here, Jill is likely talking about the male audience members who watch her showgirl act.)

Mike barely smiled. “I grok he would be missing.”

(“Missing” refers to Mike’s penchant for disappearing people into another dimension.)

“I grok he might. But, Mike—listen, dear. You promised you wouldn’t do anything of that sort except in utter emergency. If you hear my scream, and reach into my mind and I’m in real trouble, that’s another matter. But I was coping with wolves when you were still on Mars. Nine times out of ten, if a girl gets raped, it’s partly her fault. So don’t be hasty.”

Spoken by a woman, written by a man. Carried the implication that it was her ability to “cope” which resulted in her not being raped. Supposed that self-imposed trouble existed when it came to these things.

I was very rapidly pulled back down to Earth. As it were.

Stranger in a Strange Land is a book about the future, and what might survive and generate when the writer is long gone. It also occupies a decidedly contemporary space when it comes to women, race, and sexuality. A government worker is described as an “imperious female” and a “snow queen”; Duke greets another character as a “limber Levantine whore” with what we are led to believe is affection; one character treats his collection of female statues better than his harem of women servants.

So much of the futuristic imagining of the book is sexual in nature, and it’s in part meant to lampoon prevalent attitudes toward sex at the time. Multiple partners and orgiastic water parties are central to Mike’s religious cult, and when one character voices objections, he’s chided and told he should let go of his ingrained conception of sexuality and see the happiness in non-monogamy. The suggestion is that he, and maybe we, should transcend our nasty, small-minded ideas about sex and embrace pluralistic bliss. Fine! And yet. A future in which everyone fucks everyone else doesn’t preclude a future in which women are annoyances unless a man says they’re not.

Why should it be a surprise that such bumbling misogyny is hidden in plain sight in one of the most popular science fiction books of the 20th century?

In retrospect, the shock seems almost quaint. Why should it be a surprise that such bumbling misogyny is hidden in plain sight in one of the most popular science fiction books of the 20th century, one that sold millions of copies and won the Hugo Award for best novel? Why, after floating through the past two months with gritted teeth and tense shoulders as accusations against men I once respected and sometimes knew cascaded down, should I feel a sharp pang when I see the same ethos in some man’s idea of the tomorrow? Why should it feel like a jolt of lightning to recognize the bridge between the world as we know it and some of our most popular imaginings of sex and the future? Haven’t I learned by now that this stuff oozes out of every crevice, coats the ground I walk on, slides down the walls, poisons the breath of every man I know, even the good ones?

Maybe. The relentless parade of Bad Men Exposed has dredged up every rotten or uncomfortably hazy encounter rattling around in an ever-growing but rarely accessed safety deposit box in my mind. Yet it’s also made me numb to all of the pageantry, because when you see the same rancid, dick-shaped procession outside your window every day, it gets old.

But the numbness isn’t all-consuming. And maybe it shouldn’t be. Maybe it’s good to be prodded back to reality by a throwaway line about rape. It does make you nervous, though. You ask yourself how much of this stuff is buried in the classics, or even just the things we consume when we’re teenagers, only dimly aware that these are the so-called formative years. Do we dare go back and check, or, like the stories of Harvey Weinstein and Glenn Thrush, will it only serve as a reminder that the world looks at women but never sees them?

You could chalk it up to art, or the (correct) idea that fiction is fiction for a reason. But Stranger in a Strange Land and other sci-fi novels like it are, in some ways, critiques of the present; they ask readers to wonder how things might be different in the future. The answer here, it seems, is not much.