Recently, I spent the entirety of my weekly therapy session just trying to get to therapy. There’s never a good time to leave your desk when you work in media, but on this particular Thursday, I’d been running late to my shrink’s office in the West Village after helping a writer navigate a tricky story edit. While speed-walking the half mile to the train, the New York summer heat causing pit stains to form on my shirt, I got into a text message conversation with a friend who was having trouble deciding whether to take a job promotion.

Prompting her to spell out the pros and cons of the new role was familiar, absorbing work for me — so absorbing, that I got on the J train instead of the M, and failed to realize it until the doors opened in the Financial District. I got off the train to correct my course, but got sidetracked by a Twitter DM from a freelancer asking for guidance in refining a pitch — only to discover that I’d gotten on the wrong train again, and was heading back over the Williamsburg bridge to Brooklyn. In minutes, I was back where I’d started my journey, with only 15 minutes of my session left on the clock.

I texted my therapist asking if we could conduct our conversation over the phone, and she called me back saying that wouldn’t be possible moving forward: I’d fallen back on that option too many times, and she needed to draw a boundary with me. I’d been spending so much time attending to the needs of others that I didn’t have any bandwidth left for attending to myself.

What was this force inside me, or set of outward circumstances, that was prompting me to take so many hours out of my day to assist, comfort, and nurture the people around me? It’s a behavior of mine I’ll probably be unravelling for the rest of my life, but after a Facebook friend posted an article about the invisible “emotional labor” that femme individuals perform, I felt like I’d finally found a term to describe it.

The idea of emotional labor seems to be having something of a moment. As an umbrella term for the various forms of people-work women perform, it’s there in egregious tabloid stories about Upper East Side housewives who charge their husbands an end-of-year “wife bonus” in exchange for helping their children get into toney private schools—and in op-eds from sex workers about how the services they provide can feel pretty similar to that of a therapist. In a 2015 essay for The Toast, Jess Zimmerman made a case for emotional labor as something that women should be able to put a dollar amount on, pricing “soothing a man’s ego” and “pretending to find him fascinating” at $100 and $150, respectively.

These discussions revolve mostly around emotional labor in the personal sphere, though I’d argue that women perform just as much of it in the actual workplace. Many millennial women spend the majority of their waking hours working anyway. And though they’re technically getting paid for their time, they’re shouldering an invisible workload that is seldom reflected in their job description, and even more rarely in their paycheck.

For her 1983 book The Managed Heart, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild studied the work of flight attendants to explore how employees in the service sector are forced to mask or summon certain feelings on the job. She defined emotional labor as “emotion that is sold for a wage”— work in which ornery customers are always met with a smile, and where “the emotional style of offering the service is part of the service itself.” While men certainly weren’t exempt from performing emotional labor on the job, she noted at the time, many of the careers requiring this kind of face-to-face service work, like teaching, nursing, and retail, were dominated by women.

Her study of emotional labor had echoes in the feminist discourse of the time, especially around the uncompensated labor that women perform in the home — work Hochschild would go on later in her career to describe as the “second shift.” As the activist Silvia Federici wrote in her 1975 manifesto, “Wages for Housework,” capitalist patriarchy had brainwashed women into thinking that doing dishes and diapering babies was a “natural attribute of our female physique and personality” — so men get out of paying them to do it.

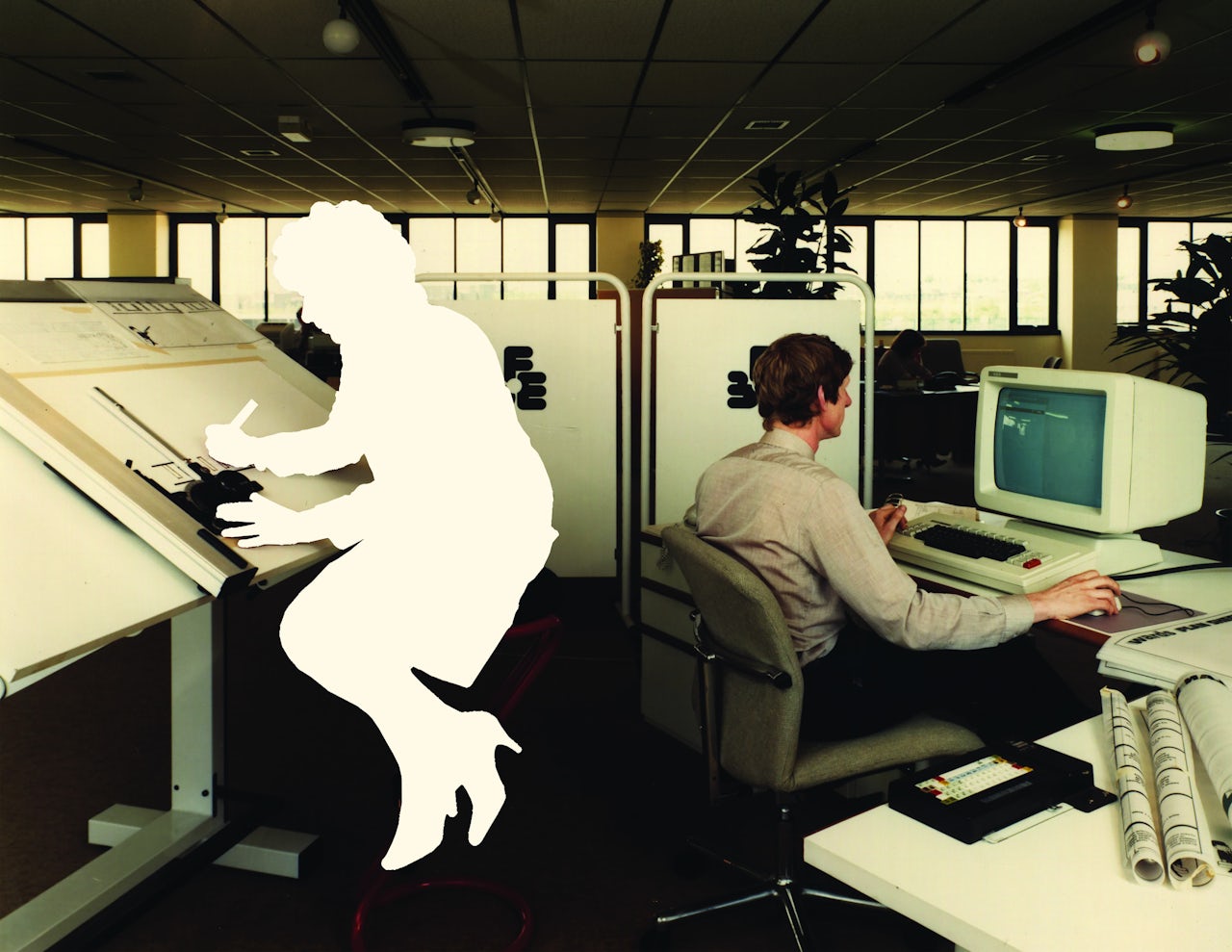

Of course, women have come a long way in the professional world since the ‘70s, even if the wage gap is still very real, especially for women of color. There have been other advances, as well. Thanks to the fact that I am an unmarried woman with no kids, I don’t have to do most of my own housekeeping. I get dinner ingredients mailed to me in pre-measured portions, pay a few dollars each week to get my laundry done for me, and use apps to remind me to about everything from managing my finances to when my period is coming.

Still, for many professional women in America, the modern workplace can feel less like a respite from the nurturer-caregiver role than a continuation of it. Nadia, a friend of mine who works as a copywriter in the tech industry, estimated that at a recent job, she spent 80 percent of her mental energy trying to figure out how to word her ideas as carefully as possible—for fear of coming off as threatening to her male coworkers.

“I had to be extraordinarily nimble all the time,” she said. “I had to sugarcoat a lot of the things I said. Some of it was just body language — making yourself slightly more diminutive and smiling a lot. And a lot of it was that I was one of the youngest people on the team, I’m a woman, and I’m black, so I have a couple of things to reckon with in an environment that’s predominately white, and male, and older. I feel like I’d watch other people say things, and I would think, ‘Oh my God, if those words came out of my mouth, people would cringe.’”

According to Rebecca J. Erickson, a sociology professor at the University of Akron, there’s research to support the theory that women and men operate under different “emotion rules” in the workplace. From her work studying the connection between emotional labor and gender, she said she’s observed that women in the corporate world tend to rewarded for expressing “positively valenced” affects like happiness, kindness, and supportiveness, and punished for displays of fear and anger — fear, she said, “because it’s perceived as weakness,” and anger “because women are trying to avoid being labeled a bitch.”

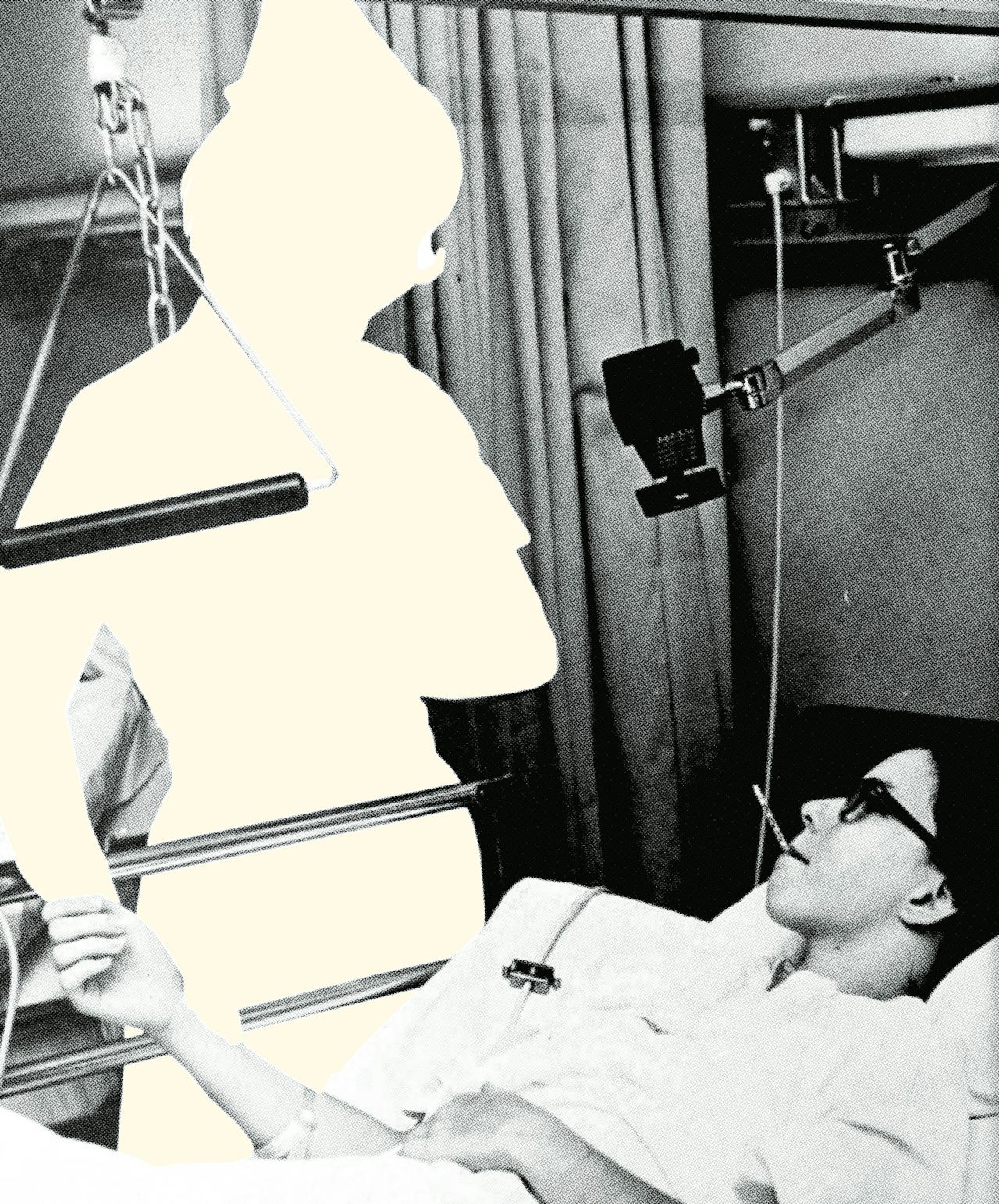

Men, by contrast, tend to receive what sociology calls a “status bonus” when they express anger, assertiveness, and other emotions associated with power. And where women are restricted to a very narrow range of emotions on the job, men can be rewarded for displaying any emotion at all. According to Erikson, research suggests that when men express emotions like caring, concern, sadness, and fear, it can have humanizing effect on them. If you’ve ever gone to the hospital and remarked that a male doctor has a surprisingly caring bedside manner, you’ll understand what she means.

Even outside traditional helping professions, there seems to be a gender discrepancy when it comes to performing this sort of proxy-parenting work on the job. One friend of mine who used to manage a team of young writers at a pop-culture website said helping her employees work through personal and professional upsets was more than something she was implicitly tasked with by her male bosses — and that it was a crucial part of maintaining the business’ bottom line.

“They’re never going to say, 80 percent of this will be convincing a sobbing editorial assistant that her career’s not over because a reputable reporter made fun of her on Twitter,” she explained. “It was this very black-and-white situation where [the bosses were] cracking the whip and being the bad cops, and I was the good cop by default. You’re basically doing maternal babysitting as work to make money for a company and get the job done.”

According to Erikson, the sociology professor, one of the hidden injuries of emotional labor is the way it siphons away energy that could be otherwise spent hitting the sort of work milestones might actually be recognized in a boardroom — and rewarded with a promotion or raise. Prolonged emotional labor may also have an impact on your mental and physical health, regardless of your gender. In a 1999 study of employees at a public university in the U.S., published in the sociology journal Motion and Emotion, workers who performed more emotional labor on the job — including managing their own feelings and managing those of others — reported higher levels of subjective job stress, lower job satisfaction, and increased psychological distress. In a 2001 survey of 522 married professionals with kids, Erickson and a co-researcher found that respondents who felt obliged to hide feelings of agitation at work were more likely to report occupational burnout, especially if they were women.

According to Lisa Wade, an assistant sociology professor at Occidental College, masking or faking certain emotions — a process known as “surface acting” — can lead to existential confusion. “Some of the research shows also that it distances you from yourself in a way that is very psychologically disturbing,” she told me. “You’re faking it so much, that you start to feel like you don’t know who you are anymore.”

It’s hard to imagine a profession, outside of therapy or social work, in which emotional labor might be explicitly associated with a price tag. In fact, it’s probably a bit foolhardy to look to capitalism for a solution to the emotional labor gap. In professions that are traditionally gendered “female,” like nursing, pay rates only tend to go up when men enter the field. When asking whether women should or could be compensated for this additional labor at work, it’s perhaps useful to consider other forms of conventional women’s work that people in America are regularly paid to perform, like low-cost house-cleaning and laundry services.

“Usually, when someone gets paid to do the work of the unpaid wife, they get paid very low wages and no benefits, and it’s almost always a woman that comes in to do the work,” Wade, said. “It’s not advancing women for you to get out of doing labor that is undervalued, which remains undervalued. I suspect that if these kinds of apps become popular, it’ll be men that mostly get rich off these products, and it’ll still be women using the apps.”

Monetizing emotional labor may not be the answer, but there’s real power in calling it for what it is, whether you’re talking a friend through a breakup or helping a coworker organize his or her time better: arduous, skilled work. After all, when Silvia Federici demanded wages for housework, the “getting paid” part was kind of beside the point. “To demand wages for housework,” she wrote, “doesn’t mean to say that if we are paid we will continue to do it.”

Instead, Federici saw the request as something revolutionary in itself, simply “because the demand for a wage makes our work visible.” The next time your boss asks you why you didn’t turn in that project proposal on time, maybe it’s something you can bring up: “I haven’t gotten around to starting it yet, because I’ve spent the last three hours performing emotional labor with two of my direct reports.” And then, at the end of the day, you can go home to your messy room, order Seamless, and turn off your phone.