On the day when he became the most hated poet on the internet, Collin Andrew Yost — 26, bearded, tattooed, and boyishly handsome — was loading fish into a huge rubber tube. The fish were going into a truckbed that acted like a giant aquarium, to be delivered to rivers or hatcheries or wherever they needed to go. A winch on the tube suddenly started spinning out of control, and Collin’s hand got caught. His fingers instantly bruised, one of them fracturing. A softball-sized welt swelled on his right forearm. From up high, he dropped his phone: it hit metal and landed on concrete, shattering completely.

When Collin got home, he laid down on the couch to rest. It’d been a hectic day. He got up to check Instagram on his desktop computer. Though Collin worked as a marine scientist, his passion was writing. He shared his poems with nearly 10,000 followers on the social media platform, and he’d expected to find the usual likes and comments on his poetry. Instead, he was greeted with something very different. Comments like: Wow. I think I got cancer reading this and Kill yourself and Pig. Misogynist pig. Someone wrote that Collin was getting destroyed on Twitter (crying laugh emoji). “I was a little panicked, but I didn’t really know what to do,” Collin later told me. He went to his car and called a few of his close friends using Bluetooth. His friends found the Twitter thread for him. It was “really bad,” they told him. They warned him not to look.

The next day, when he got a new phone, he opened Instagram to find more than 115 direct message requests. “I was dreading to look,” Collin said.

The tweet that skyrocketed him to internet notoriety was written on August 28 by a user named @badplantmom, whose Twitter bio reads “microwaved marshmallow peep.” It shared four of his poems underneath a simple, damning line: this guy is a PUBLISHED author.

this guy is a PUBLISHED author pic.twitter.com/aqxif0N9Xk

— izzy (@badplantmom) August 28, 2017

The tweet quickly went viral, garnering 6,200 retweets and 24,000 likes. Nearly 900 comments piled up, competing in how to best mock Collin and his work. They were witty, sharp, relentless:

“Who hurt him”

“He deserves to be beaten up in a strip club parking lot, while Bukowski rolls by in a limo and does not notice.”

“Can't tell if I'm crying bc it's so funny or so so sad.”

“i want to take one of those cigarettes, light it and set that garbage on fire.”

“Is he 14 and are his parents cousins”

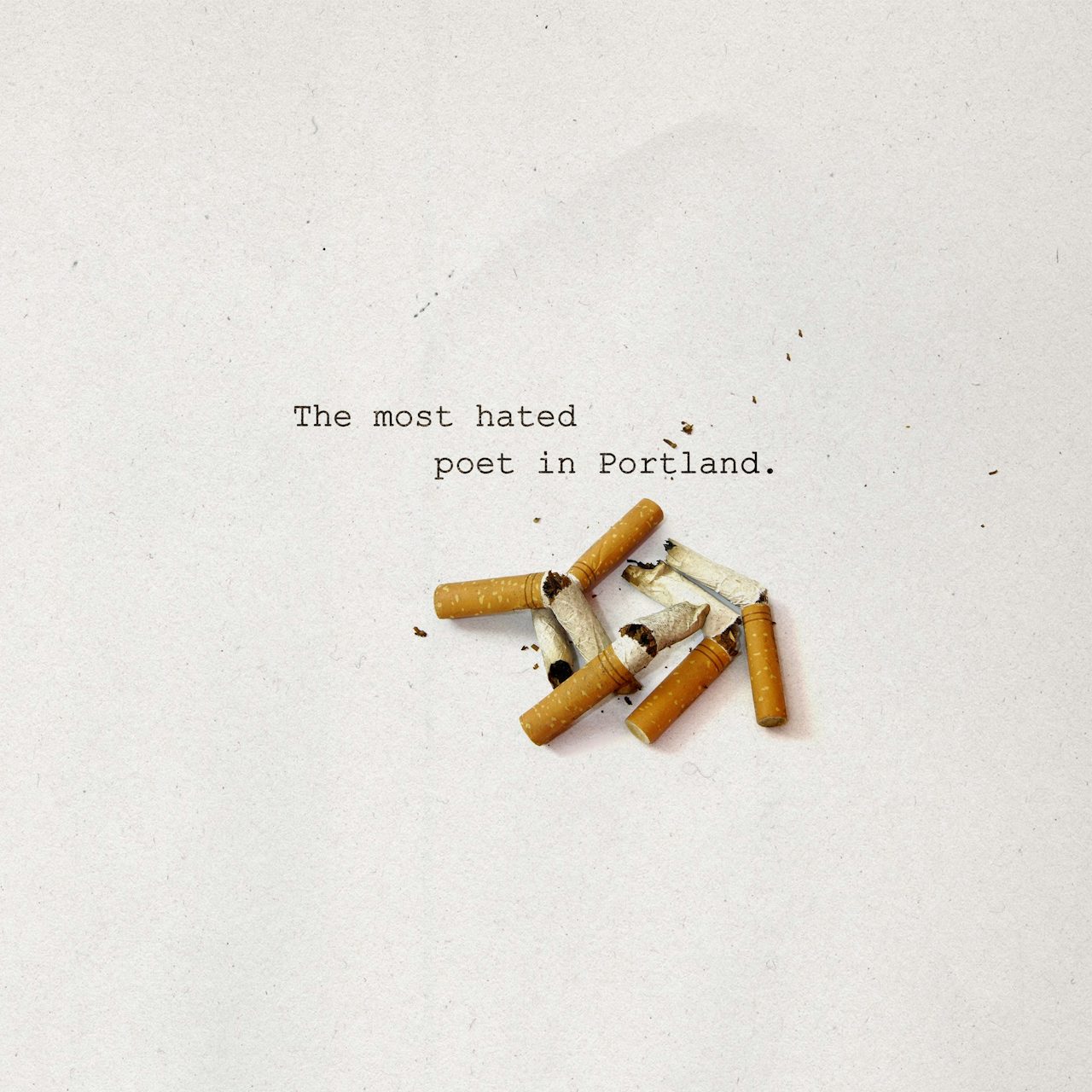

Users created parody poems using bad graphics and typewriters. They mocked Collin’s outfits: “is this a costume?” One user tweeted a photo of Collin in a short-sleeved white button up and jeans with conspicuous rips. A parody account, @WhitePoeticEdgelord, sprang up, bearing the bio: “I'm a bland white guy who thinks my one mission on Earth is to share the edgy poems written from my limited, privileged, unoriginal point of view with humanity.” The press picked up the story, too: “Everybody Hates Portland’s Cigarette Bro-Poet,” wrote Willamette Week. The online literary journal Electric Literature called it “the saga of Brobert Frost” and “a master class in mediocrity: who notices it, who doesn’t, who gets to have it without consequence, and who is so inured to their own that they mistake it for depth.”

I first saw Collin’s poems when a friend shared @badplantmom’s tweet — instead of joining the pile on, however, he’d tweeted that the comments seemed excessive. I’d felt a flash of anger as soon I clicked through to the poems. Collin struck me as a familiar type: the sort of man I fell for in my early 20s, emotionally unavailable, obsessed with how a girl made him feel rather than seeing the girl as a person herself. How could my friend fail to see it? I thought. Was it because he, too, was white and male? I dug deeper into Collin’s poems and started joking with my friend on Twitter about writing the ultimate stunt piece in which I, woke feminist/writer of color, tried to date Collin. Would he break my heart and write poems about it? By the end of our exchange, I’d written my own parody of Collin’s work, and my friend had inadvertently joined in the bashing. I was no longer angry. I was having fun.

A week later, I saw that Collin had written a poem responding to his critics. It felt surprisingly earnest (what you create is what your heart screams out for/and you must never let that fire go out), and I became genuinely curious. I decided to email Collin, asking if he’d talk. He wrote back a few hours later, cautious. Before I’d had the chance to respond, he sent me another email that made me feel a wave of guilt: he’d seen my tweets mocking his work. He declined the interview with more grace than I’d expected. “To have the internet personally cyber-bully you without any context of your work or you as a person is mind numbing,” he wrote. “I hope you can understand where I am coming from.”

Collin’s email made me see him in a more human, and familiar, light. In my early 20s, I used to share short stories and poems on Tumblr. I wrote Instagram-style poetry about melancholy and longing (“I care too much/more than I want to/less than I should,” goes a poem from 2009). I didn’t use a typewriter, but I sometimes used a typewritten font, and saved poems as images that were easy to share. I knew what my readers responded to and I had not yet learned to examine the toxic, underlying assumptions in my work (why shouldn’t I have cared? There was no point in denying my emotional needs, in trying to be the cool girl).

Something else: two years ago, I wrote a personal essay for XOJane about my terminally ill ex-boyfriend, who was a pathological liar. It was near the beginning of my freelance career, and I was thrilled with the idea of getting paid anything for my writing — this was before the backlash of the personal essay industrial complex, before I learned that I could write as well when I looked outside myself. When the essay went live, I was stunned by the comments. They were petty, vindictive, personal. You’re a terrible writer, they said, in increasingly creative ways. I remember how it felt, reading those comments, that turn in my stomach. It stung.

I wrote Collin a long email. I apologized for my tweets, explaining that I understood how he felt, that I wanted to know, honestly, his perspective on what happened. His responses to me, over numerous emails and Instagram direct messages, varied from apologetic and gracious to suspicious and defensive. “I constantly am watching my back and haven't been sleeping well,” he wrote. He didn’t want to draw more negative attention to his work. Having seen my tweets, he said, he wasn’t sure I would present a fair view. The tone I got from his emails, from our messages, was different from the idea of the person I’d formed in my mind. I asked Collin to take a leap of faith: I told him I wanted to tell his side of the story, and get to know the real Collin Yost.

Collin grew up on two farms in “a tiny-ass town with a blinking red light” in Ohio. His mom was the head secretary of the elementary school he attended, his dad an engineer. When Collin was young, he spent a lot of his time outdoors, hiking, riding horses, and playing sports with his two older brothers. He was a self-described “giant goofball” who talked often and unironically about being true to oneself. He studied biology in college, inspired by his visits to his grandparents in Florida, during which they’d often go fishing or swimming with the dolphins.

He’d moved to Portland for work (“a lot more fish out here than Ohio”) in June of this year. He loved the city: the art and fashion and food scene, the coffee shops and the time he spent walking around, his little two-story house on a hill, where he lived with two newly adopted kittens named Truman and Sylvia.

Collin had started writing poetry as a way to deal with the anxiety that he’d had throughout high school and college over “normal things,” like wanting to be liked or to fit in. “Staring at it on a piece of paper made it seem weaker, like I could conquer it,” he wrote to me. It was Collin’s friends who suggested that he start sharing his work online, so he started peppering his Instagram feed with handwritten poems. “I never intended for people to think I was legit,” he said.

One day last summer, someone broke into Collin’s car. They took his most valued possession: a backpack in which he kept all the poems he’d written in the last two years. He was devastated. “I don’t think I was more lost in my life. I sobbed on the phone to my dad — he thought something was seriously wrong,” Collin said. The next day, he bought a 1978 IBM Selectric II from Craigslist. He’d grown up using his grandmother’s typewriter — he loved the adrenaline rush he got from using it, and he liked the way his poems looked. They were perfect for Instagram. Soon, he found himself becoming a part of a growing poetry community on the app.

In January 2017, he self-published his book, A Shot of Whiskey and a Kiss You’ll Regret In the Morning. “[Self-publishing] is huge in the Instagram community,” Collin told me. The controversial (and now best-selling) poet Rupi Kaur self-published her first book, Milk and Honey, too. The community members push each other to self-publish and buy and share each other’s books. He hadn’t anticipated that the book would become popular. “I honestly just expected friends and family to buy it,” Collin said. He only had 1,000 followers on Instagram when the book came out, but a few months later, one of his poems ended up on the app’s discover page, and his follower count quickly grew. By late August, he had almost 10,000 followers; his book appeared on Amazon’s “Hot New Releases” page, and got picked up by Barnes & Noble. He started working to get it placed in local bookstores like Powell’s in Portland, where Izzy Leslie — or @badplantmom — discovered it a few months later.

Izzy, a bubbly 24-year-old writer and visual artist, often liked to browse the small press poetry section Collin’s book stood out to her for all the wrong reasons. The title, Izzy told me, “sounded like a country song.” The book was full of poetry cliches (roses, romance) and felt “just so, so over the top.” Izzy was so struck that she wrote down Collin’s name on the back of her hand so that she would remember it later.

That night, on Instagram, she found even more to dislike. There was the cigarette “skillfully placed” in every photo, and the apparent misogyny in his poetry. Collin’s poems seemed “hyper-masculine,” Izzy said. “I didn’t see very much respect for women based on the way he [wrote] about these romances.” In one of the most offensive poems, he portrayed himself as an intellectual bad-boy: a half naked girl in his bed: “she loves my tattoos / and how I seem not to care about anything.”

“It just seemed like such a disingenuous and cliched fantasy of himself,” Izzy said. “It made me feel like he [was] very insecure.” In another poem, he used the line “she wasn’t a whore but she fucked like it,” which felt both “cliche and icky to women and sex workers.” Aside from the misogyny, she disliked the way the poems felt pretentious, like Collin was “cosplaying as his idea of a poet.” So on August 28, she took screenshots of Collin’s most offensive poems and shared them on Twitter to her 300-something followers.

As an idea, Collin the Instagram poet represents the white male mediocrity that all too often gets rewarded: with fans and accolades and multimillion-dollar publishing deals. With his many Instagram followers and seemingly successful self-published book, Collin became part of a literary history dotted with misogynistic-yet-celebrated-men and bright-yet-overlooked women. This is a culture that responded to a woman writer, Catherine Nichols, more positively when she submitted manuscripts under a man’s name: when she sent out 50 queries under a male name, a third of the agents she contacted requested to read more. The same query, sent under her real name, got a response one in 25 times.

For many women, recognizing misogyny is an instinct, something you viscerally feel even if you can’t explain it. But by the time Izzy’s tweet became viral the next morning, the comments no longer seemed to be just about misogyny. They started to feel theatrical and performative, about who can come up with the funniest tweet or the most biting satire.

According to Dr. Elias Aboujaoude, a Stanford University psychiatrist and author of Virtually You: The Dangerous Powers of the E-Personality, there’s “something thrilling about expressing yourself without any breaks on what you say.” If a friend showed you his poetry over coffee, for instance, you’d find a polite way to express your dislike, if you share your opinion at all. But online, we speak “without worrying about consequences to you or the person on the receiving end.” This can be fun, liberating, even “entertaining or smart in some situations.” But it can also become dangerous.

The internet, Aboujaoude told me, changes the way we behave. The constraints that govern most of our daily interactions — culture, religion, a sense of propriety, tact — disappear. Beyond a screen that gives you anonymity, things escalate quickly: one tweet turns into hundreds and thousands of comments. “Impulsivity comes out so naturally in people’s online personalities,��� Aboujaoude said.

When something goes viral another element is added. “A lot of what we do online is look for people who agree with us,” Aboujaoude said. “It’s a way to build communities and to think that when we’re online, we’re still part of something bigger.” People can rally community around something they love or something they hate. When community builds around the latter, as it often does, the line between criticism and abuse begins to blur. “It’s very legitimate not to like someone’s poems because you find them misogynist,” Aboujaoude said. “The difficulty is how that gets expressed. You can write a very intelligent article pointing out his misogyny — but are people who are attacking him online doing that?”

A lot of what we do online is look for people who agree with us.

Izzy told me that after her tweet went viral, strangers attacked her too. They called her mean and said awful things. "Don’t YOU have anything better to do with YOUR LIFE? Like maybe eat a salad, or find some friends for your twat self?" Read a DM from a newly created Twitter account. Someone had even tried breaking into Izzy’s Facebook account. “I���m sorry that [Collin] had to go through that. It’s not right,” she told me. “I want to talk about the things that I have issues with, the misogynist point of view… otherwise it just becomes, oh we’ll all laugh at this guy for a bit and it makes me feel better about myself. We don’t need any more of that.” When I asked Izzy if she thought all the hate mail Collin received ever seemed excessive, she said yes. “I think if that happened to me, I would be super bummed. But um,” she sighed. “I don’t know what to say.” Collin, who referred to Izzy only by her Twitter username and initially seemed defensive towards her, also softened his tone as we continued to talk. “I feel like in person we probably would’ve got along and had great conversations about books and writing and Portland,” he said. “I’m sure we would disagree on things, but that’s human. I would’ve asked her why she hated [my poetry], maybe explained a few pieces so she [could] see where I was coming from, and then [moved] on with our lives.”

When I reread some of the 900-something comments in Izzy’s Twitter thread, they no longer seemed witty or fun. The comments (I am an avowed pacifist... but I want to kick that guy in the nuts; published in what, his group therapy newsletter?; did he fuck the cigarettes. i feel like he fucked the cigarettes) felt cruel, and if there had been a grain of righteous anger in them, it’d become displaced by accusations and assumptions that were far from the mark. For instance, various people mocked Collin for being a living version of the @GuyinYourMFA, a parody account that embodies the posturing, self-obsessed male artist in the creative writing program, but Collin told me that he had no idea that trope even existed.

There isn’t group of people who are more or less susceptible to the tendency to gang up on the internet. “Everyone online falls somewhere on this spectrum,” Aboujaoude told me. Because there are so few filters as to how people express themselves, these impulses to react, to pile on, “surface automatically.” It doesn’t matter if you’re fighting against misogyny or support male pick-up artists: the inclination to speak out works exactly the same way. Some people view this lessening of boundaries — of not having limits on what we say — as liberating. But Aboujaoude thinks it’s dangerous. “If you lose the ability to control…impulses like that, civilization and culture itself has turned,” he said.

New mediums of communication often produce cultural shifts, but the internet is an especially pervasive presence. iI’s all around us, accessible anytime, and you’re an active participant online, not a bystander, even if you think you’re there passively. Habits and norms that develop online might invade offline life, too. So what happens when, online, we learn to be less empathetic to the other side?

The internet echo chamber goes both ways. On Instagram, Collin’s followers regularly give his poems thousands of likes and tell him that he’s changed their lives. They ask him where he gets his inspiration and request writing advice. After the infamous Twitter thread, other Instagram poets jumped to Collin’s support (some of them, I suspect, even created anonymous accounts to redirect the hate back to Izzy).

For the most part, Collin frames his brush with Twitter infamy with uplifting platitudes: love eventually conquered hate, and hate eventually backfired (he got more than 5,000 new followers after Izzy’s tweet went viral, he said). But it was clear that the incident changed him. “I went from [being in] a close-knit Instagram family to being a woman hater and this ‘bro’ to all these strangers,” Collin said. “I mean, it sucked.” Now, some mornings, he wakes up a little afraid to look at his phone. But then again, his friends told him, maybe that was a sign that he was getting it right, on the road to making it. Collin enjoyed his work as a scientist, but his dream — like almost everyone who writes, he said — was to inspire people, give “people an emotion when they can’t find it themselves.”

I asked Collin if he thought there might have been any validity to the criticisms leveled against him. “No,” he said immediately. “I’m completely fine with criticism when it is actually criticism. But saying “you’re a pretentious dick and your writing is trash. please stop. hope you die” isn’t criticism. That has been 99.9 percent of the comments and messages.”

And so Collin, with his cigarettes and typewriter and goofy smile, continues to share poems on Instagram (at least when you were with me, you were an artist/now you’re just someone’s girlfriend/I’m not sure who that hurt more, goes a recent poem). “It shouldn’t matter if your ‘poetry’ sucks,” he said. “You wrote it. You created something, you molded words together and it means something personal to you… to me, poetry is simply being pure and honest with yourself.”