At far-right rallies across the U.S., an English tennis champion named Fred Perry hovers, invisible to the men unwittingly representing him. For the last two years, members of the Proud Boys cult of masculinity have worn Perry-branded striped-collar polo shirts with a Wimbledon-inspired laurel insignia as they shout at anti-fascist protesters and take rocks to the head. In blog posts and tweets dating back to 2014, their patriarch Gavin McInnes has instructed them that this — a Fred Perry cotton pique tennis shirt, always in black and yellow — is the proper armor for battling multiculturalism.

The Proud Boys at most have a few hundred active members, but they are a fixture at fascist “free speech” events like this month’s anti-Muslim marches, where they mingle with white supremacist and neo-Nazi groups. McInnes is eager to point out that the Proud Boys accept people of color, Muslims, and Jewish people — so long as those members also “accept that the West is the best” and reject non-Western immigrants to America (McInnes is Canadian). But McInnes insists his followers are not themselves white supremacists, a clarification he has to make partially because Fred Perry polos have a history of popping up at racist skinhead punk shows and rallies across Europe and the Americas. The shirts have been a fixture in some form or another, in all their two-dozen-plus colorways, in both fascist and anti-fascist politics for fifty years, here in the States but especially in England, where both the brand and the skinhead subculture that co-opted it are from.

In the mid-1960s, a movement emerged when first-generation Jamaican and Barbadian Brits, whose parents had been recruited by the tens of thousands to help rebuild England after WWII, introduced their white working-class friends to ska, rocksteady, and rude boy style at clubs around London’s council estates. “You could see the music was bringing these different cultures together, and it was suggesting a possible way forward through understanding our differences,” Don Letts, a filmmaker, DJ, and BBC Radio host, who was born in London in 1956 to Jamaican parents, told The Outline. In 2016 he produced the BBC documentary The Story of Skinhead, mostly to correct the record on skinhead culture’s non-racist origins. “Politics wasn’t really something that we talked about. That was on our parents’ level. We just wanted to bond over music, clothes, and girls.”

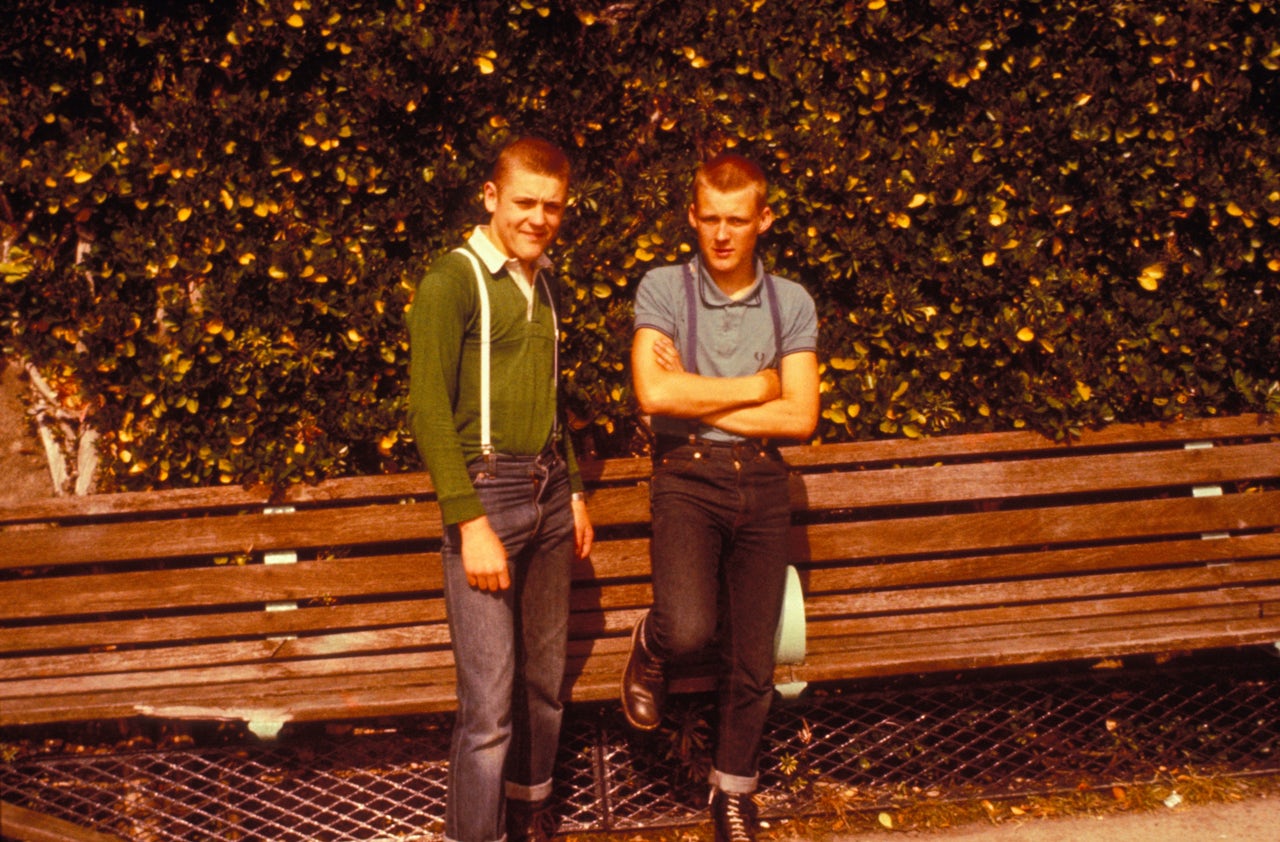

Amid England’s entrenched class consciousness, taking pride in looking nice as a working-class person inspired the white English kids to spin together their own heritage with their West Indian neighbors’ sleek suits, dress shoes, and generally smart style. “They went for things that were associated with the English upper class and looked clean and sharp but were more affordable, and Fred Perry was definitely one of those things,” Letts said. Paired with work boots and tight jeans, Perry’s designs for the tennis court became a subversive dig at English elitism. The look, which according to Letts appeared mostly on white kids but a few black ones, too, was also a response to flamboyant, middle and upper-class mod culture; before the term “skinhead” finally began appearing in the late ‘60s, the young white kids with short-cropped hair and crisp workwear were called hard mods.

As young people were working out this visual identity, white English adults had become convinced that black and South Asian immigrants were taking their jobs and ruining the economy. In 1968, conservative MP Enoch Powell delivered a now-infamous, vitriolic speech in which he warned white Brits that they would soon be an oppressed minority in their own country, punished by a politically correct government for daring to reject multiculturalism. “After that speech, I felt the atmosphere change immediately,” Letts said. “Race really came into the picture and the scene became more hostile.”

The more ostracized and feared they were, the stronger their identity became.

Skinhead culture began migrating north, to predominantly white communities where football matches were the main source of distraction from a deteriorating economy. Fred Perry’s wide color range gave fans plenty of options to show which team they supported, and the look emanated a tough edge well suited to the violence simmering underneath football culture. Ensconced in white suburban bubbles, these boys became a natural target for the U.K. National Front, a rapidly growing white nationalist party founded in 1967 that often recruited outside football stadiums.

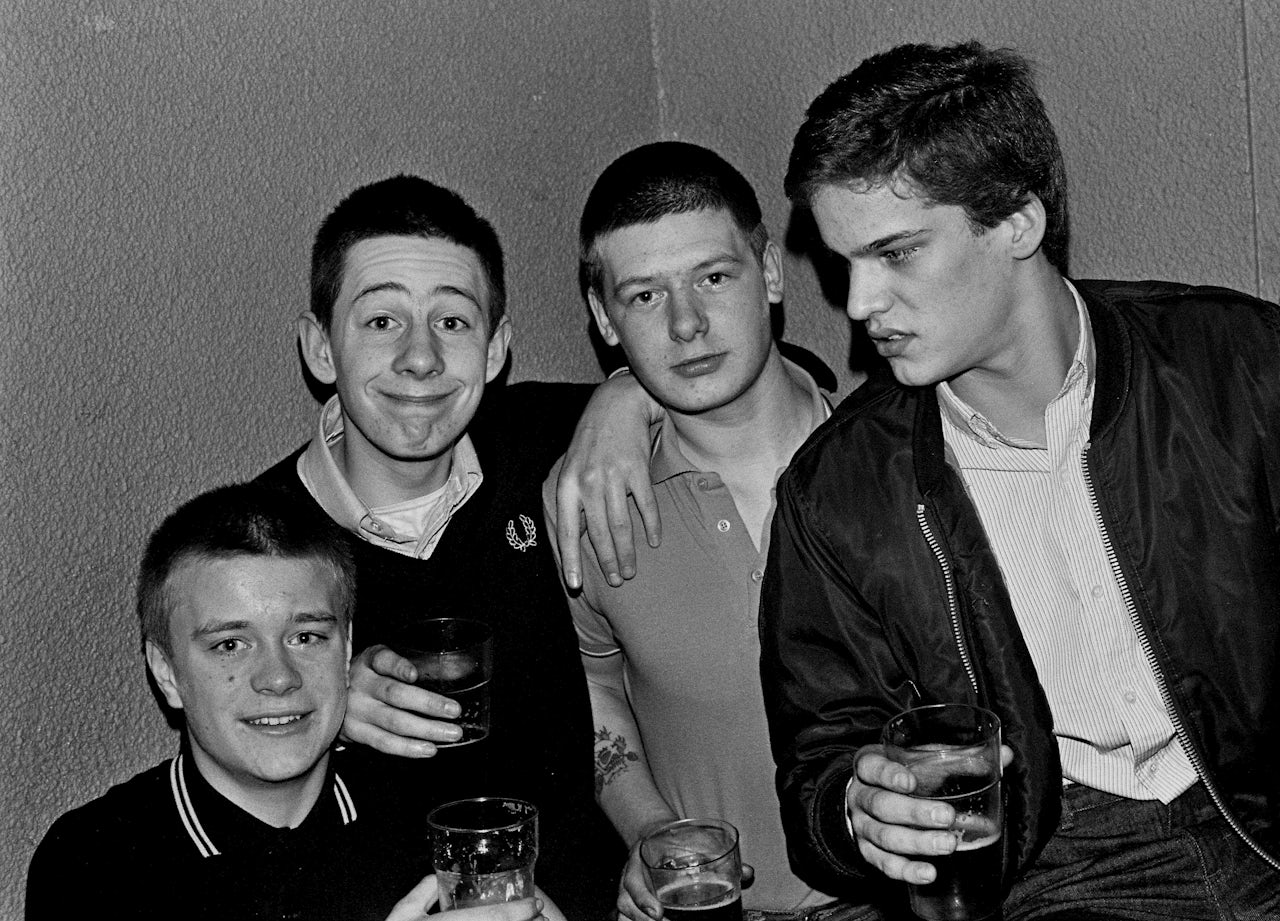

The party also opened social clubs across northern England that hosted live music, giving working-class kids — many of whom, proud of their class status, by then identified and dressed as skinheads — a place to congregate and commiserate about their dimming futures. “But you could only get in if you signed up to be a member of the National Front, and up north it was probably the only club, and so of course they wanted to go there and hear music,” Letts explained. “A lot of it came down to ignorance and just following the herd. These kids didn’t have any formulated political views.”

We discussed this story, and Gavin McInnes, on our daily podcast, The Outline World Dispatch.

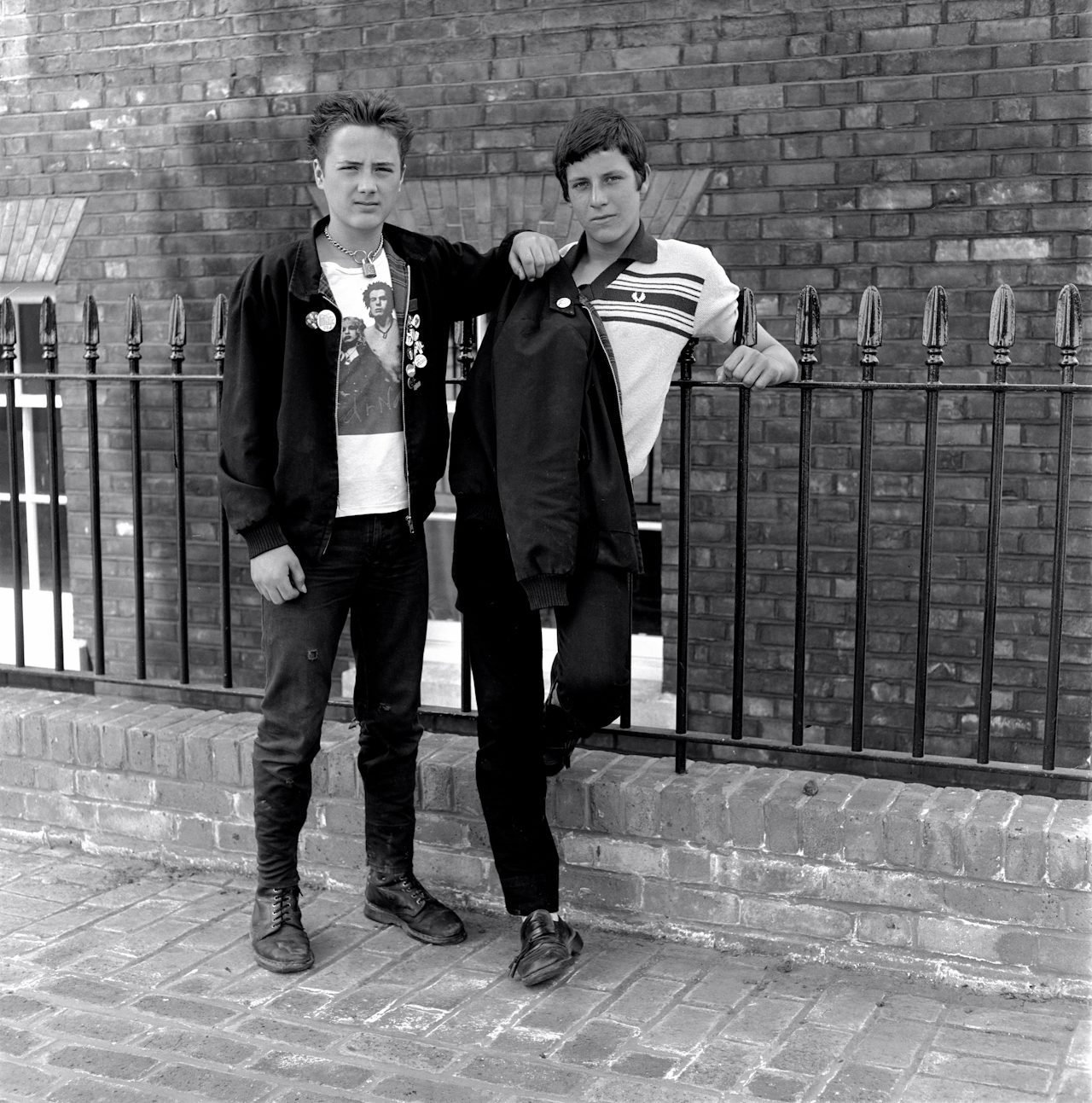

As the ’70s progressed, mainstream media became fascinated with this young, fashionable, seemingly new strain of the far right. The skinheads loved it; the more ostracized and feared they were, the stronger their identity became. Like today’s Pepe trolls, any attention was a godsend. Even when framed as reprehensible, racist ideology aired in public forums exposed more people to the skinheads’ views and legitimized them as being worthy of discussion. After Margaret Thatcher brought the Tories’ isolationist, neoliberal policies to power in 1979, neo-Nazi rallies bloomed across England, and there were always skinheads in the ranks twitching to brawl with anti-fascist protesters who amassed in opposition.

With Reagan’s inauguration signaling a similar shift in the U.S., skinhead culture, including the Fred Perry uniform, found a welcome home stateside when it landed in the early 1980s, according to Heidi Bierich, the director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project. “Neo-Nazi, white supremacist ideas already had a toehold in the US, and skinhead culture spread very quickly across the country,” said Bierich. In conservative strongholds like Orange County, California and in parts of northern Florida, angry white youth who were politically unwelcome amongst punk and hardcore’s overwhelming anti-Republicanism found the perfect solution in skinhead.

Since the SPLC began tracking racist skinheads in the late 1990s, Fred Perry has been a consistent enough presence that it’s one of only two clothing brands the SPLC includes in its skinhead glossary (the other is Dr. Martens). “What makes skinheads distinct is music and clothing, not necessarily their ideology,” Bierich said. “They’re very mobile and fluid. You’ll find them in white supremacist groups, in neo-Nazi groups, [and now] in ‘alt-right’ groups.”

When I emailed McInnes to ask him why he tells his followers to wear the black and yellow polos as they trawl for anti-fascists, he warned me that “if you associate us with Nazi skinheads or any implication like that I will take you to court” but went on to explain that he wants to align his group with the working-class toughness of the late ’60s hard mods. “It plays into the idea of this being a rebellious, edgy movement against the status quo,” said Alice Marwick, a Fordham University researcher who has extensively studied social media and the far right. “When you say ‘white supremacy’ you think of something with a long history, like the KKK. When you say ‘alt-right’ it sounds like something new and alternative. In that newness, people feel that they’re part of sticking it to the man.”

A few days later, he released a ten-minute video excoriating media that criticizes the Proud Boys for their uncanny similarities to white supremacists. I asked him why, if he doesn’t want to be associated with racists, he tells the Proud Boys to dress like them. He replied, “I’m not going to let the media’s obsession with Nazis dictate what shirt we wear.” The more hated they are, the stronger their identity becomes.