In the early 1970s, the white pro wrestler Sputnik Monroe worked as one-half of a tag team with the black wrestler Norvell Austin. The duo played on the racism of Memphis’ white fans, with Monroe proclaiming that “black is beautiful” and Austin responding that “white is beautiful.” Austin had dyed a silver streak in his hair to match the one in Monroe’s, and the pair often implied that he was Monroe’s son. In return, fans lobbed racial epithets.

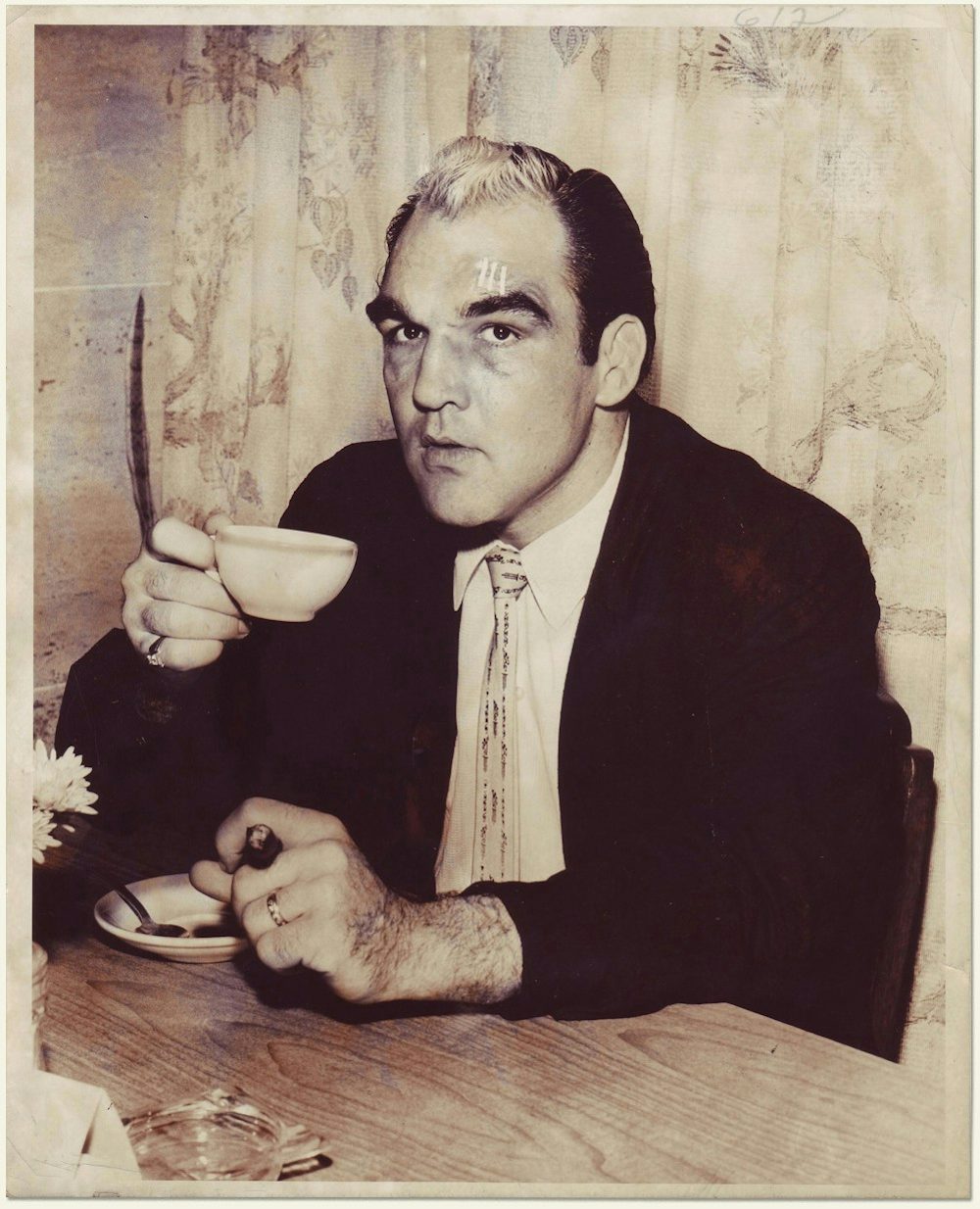

By this point in his career, Monroe had already staked his reputation as an absurdist, charismatic performer with a knack for drawing heat and antagonizing fans and competitors. “Win if you can, lose if you must, but always cheat,” he’d often mock-lecture spectators. “I’m 235 pounds of twisted steel and sex appeal, with the body women love and men fear… and no matter what happens, I never let anybody get out of there a winner!”

According to wrestling historians Greg Oliver and Steven Johnson, he earned his “Sputnik” moniker while working in Mississippi in the mid-1950s. He’d shown up to a television taping in the town of Greenwood with a black hitchhiker in tow, provoking a white woman who was a regular at the tapings. Monroe noticed that the interaction was getting a crowd reaction and so he continued to make small talk with the man until the woman called him “a goddamned Sputnik,” referencing the recently launched Soviet satellite that had terrified many Americans.

Like most wrestlers, Monroe thrived on angry audience reactions, but unlike a lot of his peers, his act took on a surprisingly progressive cast. When he arrived in Memphis in 1958, the city was in the midst of an artistic renaissance but still deeply segregated and riven by racism. The local label Sun Records had started raking in money after owner Sam Phillips signed Elvis Presley, a young performer who was an answer to the producer’s prayers: Although white, he danced and sang in a style borrowed from the black artists already on the label.

Sputnik Monroe didn’t have a master plan like Phillips, but he was about to do something similar — an early commodification of black culture and fans that has, in the decades since, become somewhat of a staple in entertainment. Eager to maximize his bottom line, he understood the ticket-buying power of Memphis’ black community, which constituted around 40 percent of the city’s 500,000 or so residents. At the time, they were forced into a segregated section in the back of the 12,000-seat Ellis Auditorium that was too small to accommodate everyone who wanted to attend. And so Monroe directed his cocky, catchphrase-spouting persona toward them, demanding that his employers allow black fans to buy general-admission tickets. His clout at the box office was so considerable that the demand was granted. Today, marketing to underrepresented consumers is a fairly common business strategy; groups as diverse as “wealthy blacks” and the “gay and lesbian community” have been identified as potential money-makers. But in Monroe’s day, the significance was deeper than money.

Much of the work Monroe did, though aimed primarily at monetizing a segment of the market that had been ignored, opened spaces for black performers to fill in subsequent years. “I heard stories from friends and relatives about African-American fans who had pictures of Sputnik in their houses alongside pictures of civil rights leaders,” said Alan Hill, a family therapist now living in Rio Linda, California. Hill discovered in his mid-40s that Monroe was his biological father. “It may not have mattered that much to Sputnik — though I’m sure it mattered more than he ever let on, because he was invested in projecting the image of a tough, gruff guy — but it sure as heck mattered to a lot of other people.”

“I did it just for the hell of it,” Monroe himself told interviewers, aware that he was about as unlikely a hero of the civil rights movement as anyone could imagine.

But according to his family and peers, the 50-year career spent wrestling in carnivals, fairs, auditoriums, and arenas wasn't just about drawing money.

“He would always tell me his career was about hustling and making money, but I know it was more than that,” said his daughter Natalie Bell, a 58-year-old nurse practitioner who lives in Tucson. “Daddy will always be remembered for what he did in Memphis: he figured out a way to promote himself to black fans and to become a hero to them.”

As a young child, Monroe, born Roscoe Merrick, witnessed “unpleasant” interactions between his white stepfather and the black people he employed in a commercial bakery in Dodge City, Kansas. “He wouldn’t go into great detail about what happened back then,” said Hill. “But he was very anti-authoritarian, very much about asserting himself when he saw someone being treated poorly.”

He left high school at 17 to join the Navy, and when he returned from the service in 1947, he began touring with a carnival. On the road, he’d wrestle any and all challengers, usually local tough guys who would bet a dollar to win five dollars if they could subdue Monroe. Monroe’s task was to defeat such a person by any means, and he usually did.

“Sputnik headbutted [his brother], knocking him out. It was a life lesson; the lesson was, if Sputnik would do that to his brother, imagine what other people were going to do.” — Alan Smith

“At one point, he made a big show of teaching his younger brother some wrestling moves, so he could defend himself if necessary,” Alan Hill added. “Sputnik headbutted him, knocking him out. It was a life lesson; the lesson was, if Sputnik would do that to his brother, imagine what other people were going to do.”

Monroe arrived in Memphis after seven years of touring backwater towns throughout the American South and West. At the time, the local wrestling promotion, which was operated by Nick Gulas and Roy Welch, was suffering a significant decline in business.

“Monroe ... brought this swaggering, trash-talking style of his, and a brand of wrestling that was very much like what we might today call hardcore: lots of blood drawn the hard way, with actual punches to the head,” long-time wrestling manager Jim Cornette said on a 2015 episode of “Stone Cold” Steve Austin’s podcast. “But way more important than that, he integrated sports in Memphis. That’s not an exaggeration at all. That’s fact; he did that.”

All of Memphis’ other public facilities, from bathrooms to lunch counters, were segregated. Altering even one aspect of how the city’s black population was accommodated, in this case at wrestling shows, could have an immediate impact on ticket sales.

“My daddy would tell you he just did what came naturally to him: He got to a new city and began figuring out how to make money,” Natalie Bell said. “He settled on a plan that made sense to him, that wasn’t too far removed from what he was doing in carnivals. He talked them right into the arena.”

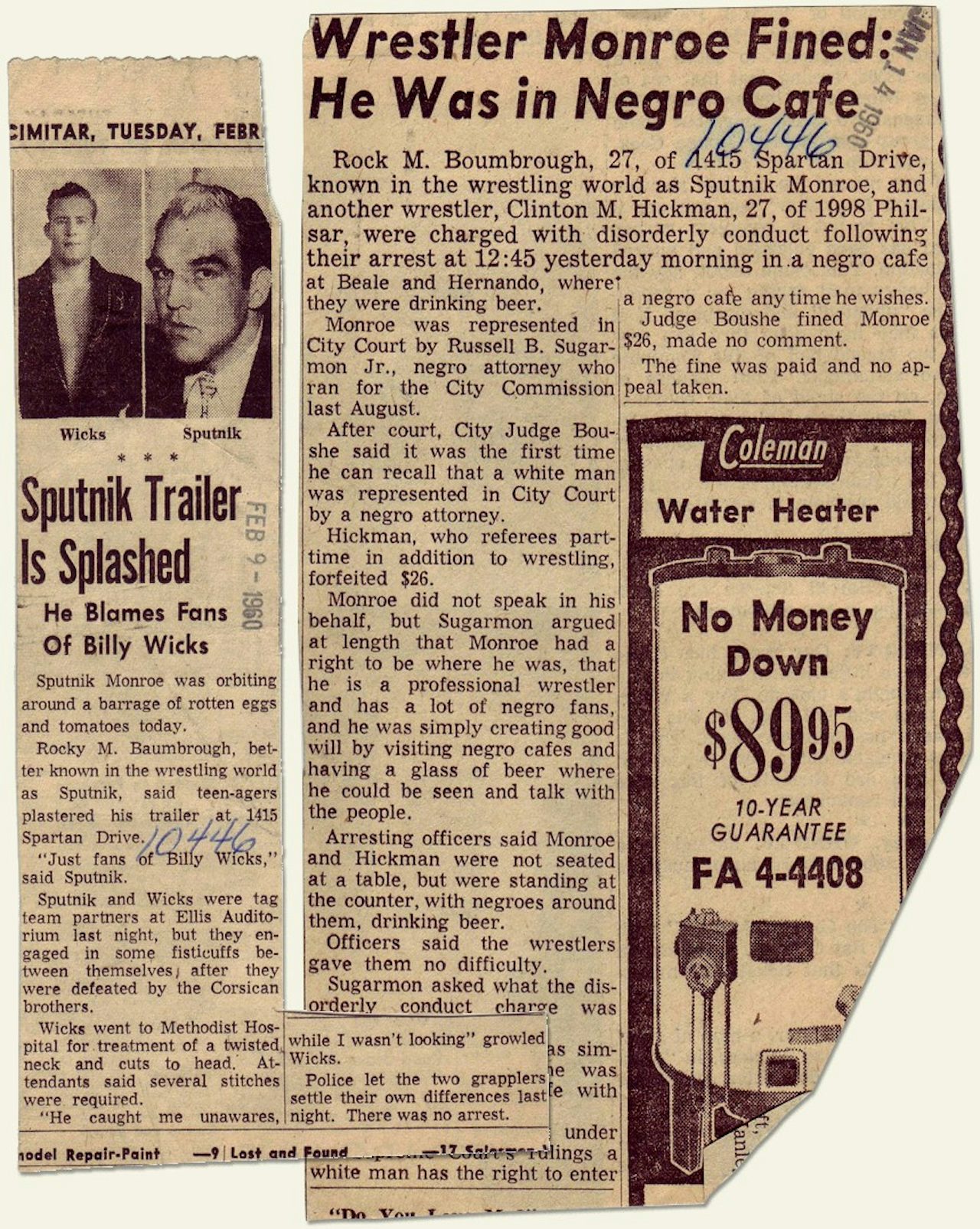

Promoters Gulas and Welch put Monroe in a months-long feud with Billy Wicks), a tough, athletic wrestler who had a strong background in both amateur wrestling and the sort of carnival grappling Monroe had done. Wicks had been built up as a blue-collar hero to Memphis’ white fans — he even volunteered with local law enforcement during his off time — and Monroe, a menacing brawler, was expected to play the foil in the dozens of weekly matches, leading up to a “blow-off” bout that would determine a winner.

Monroe had a different understanding of his part in this drama: He planned to play the role of good guy to the city’s black community. “When I arrived in Memphis, I went straight to Beale Street where the blacks hung out and from there straight to jail and got [Russell] Sugarmon, the famous black attorney, to defend me in court,” he explained to music writer Robert Gordon, who included the anecdote in his 1995 book It Came From Memphis. “They charged me with ‘mopery and attempted gawk,’ that’s an old southern vagrancy thing they made up. I was on Beale Street every night for the first six months. I got arrested three or four times until that didn’t work anymore and then the cops left me alone.”

He ate and drank with black fans, partied with them, gave them discounted coupons for access to his matches, and thus cultivated an enormous following in preparation for his main event showdowns with Billy Wicks.

“He showed promoters there was money to be made, which is maybe the best way to bring about change: Show people that money.” — David Smith

“He was down on Beale Street, kissing little black babies, and doing things [that were] not accepted. Sputnik liked the challenge of doing things society and culture didn’t want to do,” Wicks told Greg Oliver and Steven Johnson for their 2007 book The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. Around this time, Monroe attended a Memphis rodeo event, at which he antagonized several white patrons by urging them to have their cowboy boots shined by a pair of black shoeshine attendants. For his efforts, he received a beating. “The morning paper said he was kicked by a Brahma bull,” reported a witness to the assault. “He wasn’t, but he looked like it.”

But most importantly, Monroe demanded that his black fans be seated outside of their reserved sections. If they were going to fill the arenas and put money in his and Wicks’ pockets, he believed they were entitled to sit wherever they wanted. He held his ground until Gulas and Welch conceded. General admission seating at Tennessee wrestling shows sponsored by the pair were opened to all fans, and according to historians Oliver and Johnson, this remained the case after Monroe left the region. (It did not, however, apply to all events held at the Ellis Auditorium; some symphonic performances and conventions, for example, remained segregated until the mid-1960s.)

“This was a great business decision that was also simultaneously a great decision for race relations,” said “Cowboy” Johnny Mantell, a former wrestler and current president of the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame. “Obviously, it couldn’t fix everything, not even in Memphis, but it was a huge step forward...and all because Sputnik Monroe wanted to make sure he sold out his buildings.”

Monroe frequently left the area to work programs in other parts of the country. One of his most memorable feuds outside the South took place in 1964 and cast him as a trash-talking villain against “Thunderbolt” Patterson, a black wrestler who boasted a large fan following in Detroit.

“I was a black kid, and in Detroit we had our big stars — Bobo Brazil was the main one — who we cheered for,” said David Smith, a 70-year-old retired schoolteacher who now lives in Charlotte and once served as president of Patterson’s fan club. “So I knew Sputnik as a villain, and man did he fire me up.”

But Smith also collected vintage wrestling magazines, and used them to piece together stories of Monroe’s impact in other wrestling promotions. “What I recognized was that where Monroe had worked, like with his big angle in Memphis, pretty soon he’d leave and then you could see in these magazines a couple months later, whoa, you had black wrestlers sometimes at or near the top of the cards in those towns. Even sometimes wrestling white wrestlers who held title belts, which wasn’t all that common,” said Smith. “He clearly showed promoters there was money to be made, which is maybe the best way to bring about change: Show people that money.”

In the ’70s, not long after his interracial tag team stint with Austin, Monroe’s fortunes gradually declined. He remained a featured and extremely popular guest on wrestling cards throughout the Southeast, but he had divorced his wife and his finances took a turn for the worse.

When Alan Hill, who had been searching for his biological father, located him, Monroe was living in Texas. “I was told he’d give you the shirt off his back, but he let me know right away he didn’t have anything to give me,” Hill said. “But I didn’t want anything. I had gone through quite an ordeal tracking him down. And when I found him, wow...I was his spitting image. He had slowed down a lot due to all his sports injuries, but the physical resemblance was uncanny.”

Monroe’s story ended with his death in 2006, but it continues to flash to the fore from time to time. There has been talk of a miniseries, of biopics — all to no avail, even with The Wild and Wonderful Whites of West Virginia director Julien Nitzberg attached to the project. In 2016, alt-country singer Otis Gibbs released a song about Monroe that does a fine job of recapping his life and times. And Monroe figures into the background of books about Memphis and can be seen in historical displays around the city.

“My dad was like Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler, like all those old veterans. You’d be waiting for some big moment when he would reflect on his life and pour his heart out to you, but no...dad would just say, ‘I’m sorry, I get too emotional about things like that. I can’t talk about them,’” said Alan Hill. “Then he would say one of his catchphrases … and he’d be right back in character.”

Sputnik Monroe was inducted into the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame on May 20, 2017.