A saxophone screams. A saxophone honks. It doesn’t jam or shred or flow. The saxophone isn’t like a piano intro or a guitar solo. In modern music, it can feel, well, outdated. There’s no song in the Top 40 right now with a saxophone solo. There’s hardly a defined saxophone part on any of those songs at all, which is incredible because for most of American popular music’s history, the saxophone was the backbone of making a song a hit.

But add a saxophone solo to your song today, and it’s likely to get hate. A 2007 A.V. Club article about 10 popular songs “nearly ruined” by the saxophone compared the instrument to cayenne pepper: A little bit is fine, but too much is painful. When Jason Derulo’s “Talk Dirty” hit the charts in 2014, reviewers bemoaned its addictive, annoying saxophone hook. In 2015, Complex described the saxophone as “big, nasty, and damn near impossible to kill.” In today’s pop, the saxophone is used sparingly, because instead of seeming cool and propelling singles, it runs the risk of making you look corny.

Saxophone fatigue is in part the result of a decades-long reversal that took the instrument from the hook of practically every American hit to a punchline in a joke about men who think they’re sexy. That shift was made most prominent by George Michael’s 1984 smash “Careless Whisper,” whose introductory saxophone riff quickly became a stand-in for pseudo-sexiness. This is maybe best personified by Sexy Sax Man, a character played by real-life saxophonist Sergio Flores who went viral in 2011 by popping up in random places shirtless and playing the opening of “Careless Whisper.” Over the past decade, the instrument crept its way into occasional radio hits and continues to be wielded gracefully by jazz musicians. But in popular culture, the saxophone, once a staple of American music, became shorthand for a greasy ’80s man.

Big band instruments tend to pop back into mainstream music on a cycle. In the late ’90s and early 2000s, the violin made random-seeming appearances in a string of hits, such as “Beautiful” by Christina Aguilera, “Still Tippin’” by Mike Jones featuring Slim Thug and Paul Wall, and “The Scientist” by Coldplay. This year, the flute has randomly emerged as the instrument of choice on a handful of popular rap songs, including Future’s “Mask Off,” Drake and Gucci Mane’s “Both,” and 21 Savage’s “X.”

The saxophone, though, has a much more complex history: Over the past 40 years, it’s gone from pacesetter to gimmick and all but disappeared from modern popular music, with the exception of a few gleaming moments. But that’s not because people hate it. It’s because the way we hear music is changing almost as quickly as the way we make it.

Once upon a time, every band had a saxophone section. This was before World War II. Before the men got drafted, and the big bands fell apart and then became bebop, which became R&B and soul and harlem jump. Before rock ’n’ roll showed up and ponytailed girls danced to doo wop at sock hops.

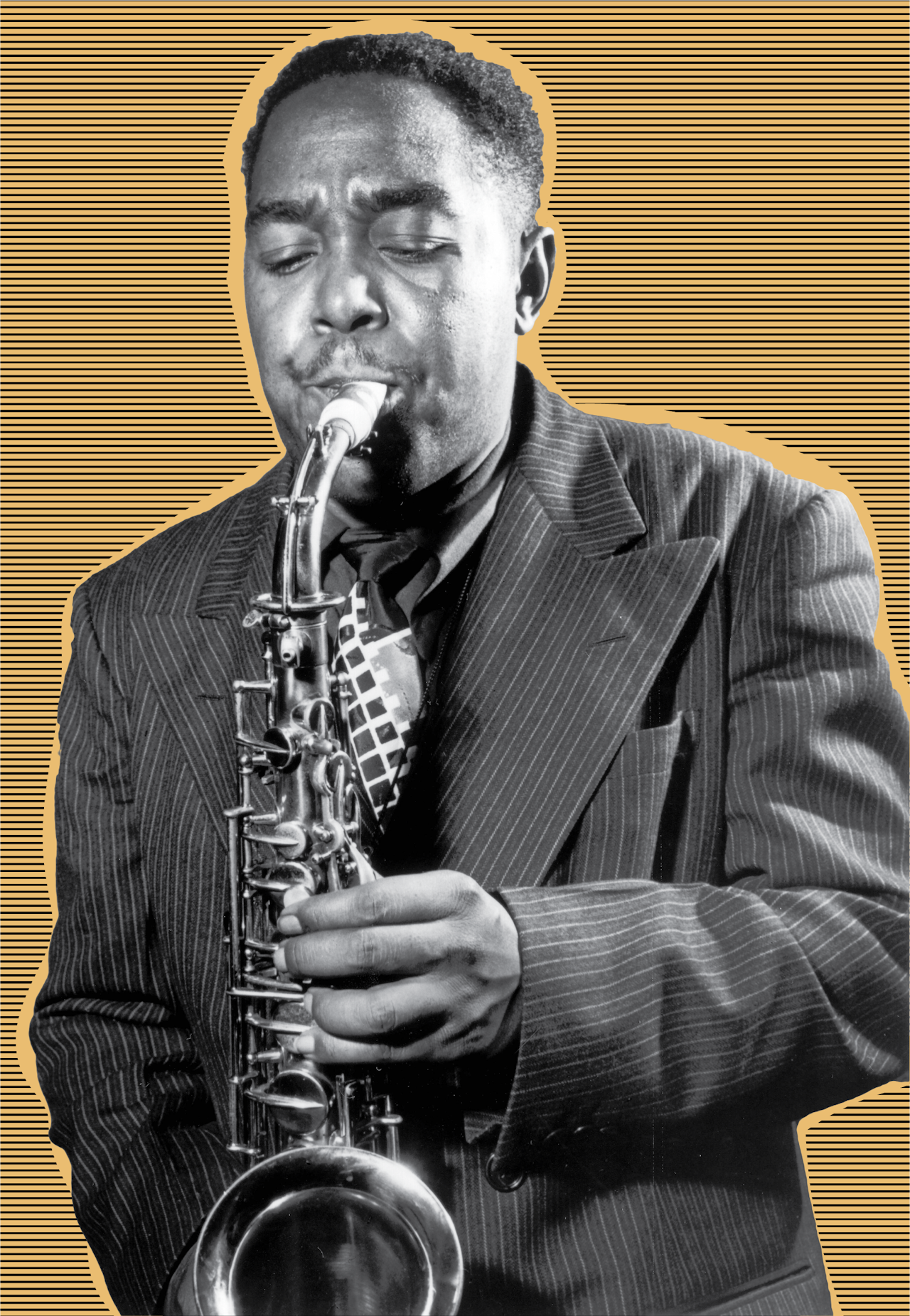

So many saxophones were needed that musicians who played other instruments switched to the big brass horn, and became famous on it. Charlie Parker, one of America’s most famous and innovative sax players ever, was so popular he was like a god. “Musicians did heroin in the hopes of playing like Charlie Parker,” Jeff Harrington, a professor of woodwinds at Berklee College of Music and a saxophone player, told me.

The saxophone, once a staple of American music, became shorthand for a greasy ’80s man.

The saxophone was built to be a big sound. It was invented by Belgian instrument maker Adolphe Sax in 1840 to be used in European military marching bands. “It took a lot of clarinets to match a brass instrument, so [it made more sense to] have one saxophone and the rest of the guys in the infantry,” Harrington explained. “It was much much louder and projected much better.” The saxophone is always the loud-mouth at the party. It’s curvy and shiny, with a dramatic shape and an unmistakeable sound. It blares, blows, growls.

The saxophone was an ideal instrument. It’s fairly easy to learn, and in the ’20s and ’30s the C Melody Saxophone was a popular parlor instrument because it could play off the same sheet music as a piano. “The saxophone is probably the most easily adaptable instrument,” Thomas Erdmann, a professor of music and an orchestra director at Elon University, told me. “Because it ranges in category from soprano, through alto and baritone, the possibilities of what you can use it for are almost endless.”

“The saxophone almost mimics a human voice,” Erdmann said. “It’s very very expressive, and that comes from both how flexible the sound can be but also the sonic quality.”

That range carried the saxophone through dozens of genres of American music without interruption until the late ’80s. When rock ’n’ roll emerged in the ’50s, it gave the saxophone another boost. “A strong hook can make a song, and it used to be that many of those hooks were created by saxophonists,” Erdman said. In the 1950s, that guy was Plas Johnson, the saxophonist behind the riffs in some of America’s biggest songs, like “Pink Panther” and “Rockin’ Robin.”

“Musicians did heroin in the hopes of playing like Charlie Parker.” —Jeff Harrington

But from there, the split between jazz and rock became too much. “Going forward from the ’60s, the saxophone [was] on a decline,” Harrington. “Sure you had some crazy wild artists and soloists, but there [was] definitely a downtick in overall saxophone use.” By the time rock became the forerunner in American music, the saxophone had been replaced with guitars. (Erdmann was careful to note that there are exceptions: Pink Floyd, for example. “It’s not like it’s disappeared, but we can see it shift.”)

That shift — toward electronic production and away from acoustic, as exemplified by the rise of disco in the ’70s — was notable. The saxophone thrived in jazz fusion with guys like Grover Washington Jr., Tom Scott, David Sanborn, and Michael Brecker. But as the genre became gentrified, there was a definite move away from saxophone sections and horn sections, to the sexy saxophone solo. Of course, no one is more famous in the popular mind for the saxophone solo than Kenny G. He and David Sanborn ushered in a new age of “smooth jazz,” an early-’80s genre that put the instrument back in the spotlight. But Kenny G achieved almost unbelievable popularity (his 1986 album Duotones hit no. 6 on the Billboard Hot 100) despite criticism of him that didn't appreciate his pop style as being distinct from traditional jazz saxophone playing.

At the same time the saxophone got its resurgence in Kenny G, its death knell began to toll elsewhere. Harrington said he sees Michael Jackson’s ascent as the true turning point in the life of the saxophone. Michael Jackson changed so much about the American pop landscape in the late ’80s, but most undeniably, he made the pop star the centrifugal force of pop music. “We start to see this shift toward the emphasis on dance choreography and the whole visual aspect of the performance,” Erdmann said. “As that moves into the ’90s and beyond, that has become a huge element of pop.”

Big name ’80s pop stars started using the saxophone to create hooks that were catchy, but inescapable and incredibly annoying. And that use took it from being a cool instrument with a strong sound, to being a weird, almost tacky gimmick. Saxophone historians skim over this section of the sax’s perception in spite of the fact that it was the site of a major turn. When George Michael used the saxophone as the intro to “Careless Whisper,” its grooving, sensual riff became a parody quickly. Sade’s “Smooth Operator,” released the same year as “Careless Whisper,” featured a classic saxophone solo not unlike the ones heard throughout popular music history.

By the time rock became the forerunner in American music, the saxophone had been replaced with guitars.

But popular music’s focus had shifted solidly from bands to individuals, and the saxophone was out of its element next to some of the electronic beats being used by artists like Madonna and Michael Jackson. (The only possible exception is, of course, Prince, who used the sax quite successfully in songs like “Girls & Boys.”) Much to the dismay of saxophone lovers, the indelicate saxophone riffs of ’80s pop became the instrument’s primary associations, and the instrument fell out of fashion.

By 1990, the heyday of the saxophone in popular music was past, but it remained a cultural artifact. When Bill Clinton played a saxophone on a 1992 episode of The Arsenio Hall Show, the move was credited with rocketing him ahead of Bush in the polls and making him more popular to black and young voters.

“I’d say once we hit the 2000s, it’s almost like the saxophone had become extinct,” Harrington said. “It’s like a dinosaur now.”

It wasn’t until the second decade of the 2000s that the saxophone peeked back into the Top 40. There were a couple of popular songs in the early aughts with big saxes, notably Jennifer Lopez’s “Get Right” and Beyoncé’s “Work it Out.” But what seemed like a major comeback for the instrument didn’t come until 2011, with the releases of Katy Perry’s “Last Friday Night (T.G.I.F.)” and Lady Gaga’s “The Edge of Glory,” both of which featured distinct saxophone solos. (Kenny G even made a cameo in the video for “T.G.I.F.”) By 2014, it seemed like the saxophone was maybe easing into another run as America’s most popular instrument. That year, it was used in Jason Derulo’s “Talk Dirty,” Macklemore & Ryan Lewis’s “Thrift Shop,” and Redfoo’s “New Thang.” Also in 2014, there was Ariana Grande’s “Problem”) featuring Iggy Azalea. None of these songs had producers in common, or even saxophonists in common. Briefly, the saxophone reappeared in the charts. And then, just as quickly, it was gone.

The evolution of studio technology was the final blow for the saxophone, according to Erdmann and Harrington. “I think part of [the saxophone’s decline in modern music] is financial,” Erdmann said, “Record companies got really involved in the bottom lines ... That meant putting less money into album production. Synthesizers came in and now you can pay one guy to do the job.”

Where recording studios like Muscle Shoals and Motown Records used to employ full studio bands (including saxophonists) to help artists build out their albums, studios today don’t have to employ musicians at all. A computer can make every sound you need. And electronic, computer-generated sounds are the driving sounds of nearly any given modern hit. By the 2000s, popular music barely had any instrumentation to it that wasn’t somehow manipulated on a computer. What mattered was voice and tone, and the saxophone just no longer fit.

Briefly, the saxophone reappeared in the charts. And then, just as quickly, it was gone.

The opening bars of “Problem,” which feature a saxophone riff repeated over and over, give a small clue as to why the instrument disappeared from the Top 40 charts just as quickly as it seemed to reappear. “The latest trend that we see saxophone-wise is this use of saxophone for rhythmic loops: these short phrases that get looped sometimes throughout the entire song,” Harrington said. “It’s a very rhythmic, repetitive thing, and it gets looped so the saxophone isn’t actually playing continuously.” But a looping saxophone riff isn’t what the instrument is made for, and Harrington’s theory is that people don’t hate the saxophone at all. They just “get sick of repetition.”

And part of that has to do with how the saxophone is made to sound today. “We’re seeing a big evolution of production, of recording techniques, and of the actual sounds. Everything’s getting sampled and synthesized ...” he added. “When we do have an acoustic instrument like a saxophone, it tends to get processed to where [it’s] almost unrecognizable.” We don’t hear many acoustic instruments in pop music in general, be they saxophones, clarinets, or trumpets; and when we do, they often sound out of place.

To be fair, the saxophone has always retained a position of importance in jazz. And the genre's resurgence over the past couple of years has made space for the instrument. Young jazz bands, like New York’s Onyx Collective, have reinvigorated the genre; established saxophonists Kamasi Washington and Terrace Martin have collaborated extensively in rap, R&B, and soul, finding fanbases beyond jazz; and artists such Blood Orange and M83, who draw inspiration from ’80s pop, have feature sax riffs on critically acclaimed albums.

Still, those influences have yet to bleed over into mainstream pop. “Whatever we’re doing eventually gets old and we need to go elsewhere and look for something else,” Harrington said. “I’m hopeful that soon we’ll be returning to less processed music.” But it also means that a big comeback could be on the horizon.

“Everything’s cyclical right?” Erdmann joked, “I mean even polyester pants came back.”

Corrections: A previous version of this story misattributed the quote “People did heroin just to be like Charlie Parker” to Jeff Harrington. He actually said that “[m]usicians did heroin in the hopes of playing like Charlie Parker.” A previous version of this story described Kenny G's popularity as being matched by criticism; it has been updated to more accurately represent his success.