American Top 40 is the No. 1 syndicated radio program in the United States. The show airs on iHeartRadio top 40 stations across the country and is hosted by the beloved Hollywood interviewer Ryan Seacrest. There are 150 iHeartRadio-owned top 40 radio stations that play top 40 hits 24 hours a day, every day, plus an iHeartRadio app that streams the stations. A hit played on top 40 radio is unavoidable, and can become a “song of the summer,” showing up in retail establishments and car rides alike. If anything creates the soundtrack to an American life, it’s those stations.

The weird thing about the top 40 stations, though, is that they aren’t really playing the top 40. Or at least, they aren’t playing the list of songs that everyone else considers to be the definitive version of the most popular songs in America: The Billboard Hot 100 chart. If you examine the American Top 40 chart, which is published weekly on iHeartRadio’s website, there are some striking differences. The American Top 40 chart includes more dance songs, more songs performed by DJs, and significantly more white artists than its counterpart, the Billboard charts. On the most recently released chart from American Top 40 radio (dated February 11), nine songs are performed by black artists. On the Billboard Hot 100 chart’s top 40 for the same date, 15 songs are performed by black artists. I looked back at the 15 previous chart weeks as well, dating back to October 29, and the trend maintained. While the Billboard charts averaged 43 percent black performers in their top 40, the radio stations stayed just under 20 percent.

Many popular songs by black performers rise into the Billboard top 40 after a viral release and without the backing of major labels with the political leverage to get their songs onto American Top 40 radio. For the week of February 11, for example, “Juju On That Beat” by Zay Hilfigerrr and Zayion McCall was at No. 30 on the Billboard Chart and not on the American Top 40 chart at all. But of the seven songs by black artists that were in the Billboard top 40 for that week, only two of them were made by independent labels. The other five were the products of Atlantic, RCA, and RocNation, all labels with the backing to maneuver a song into a top 40 radio program.

Why is this? As Eric Weisbard, an associate professor at the University of Alabama and the author of the book Top 40 Democracy, told me, “People are structurally being given a whiter version of the top 40.” The top 40 songs that Americans hear on the radio aren’t the empirical top 40. American Top 40 radio is “functioning as a kind of filter that makes something softer, whiter, older,” Weisbard said.

To wit, Rae Sremmurd’s “Black Beatles” hit the Billboard Hot 100’s top 40 on October 22, 2016, and closed out the year at No. 1. In the 18 weeks since, it has been unquestionably one of the most popular songs in American culture. But “Black Beatles” didn’t reach the American Top 40 chart until January 7, 2017 — after it had already been the No. 1 song on the Billboard chart for seven weeks. This is no coincidence. The split along racial lines between the top 40 stations and Billboard charts started in the early 1990s, and has led top 40 radio stations to be whiter and more outdated than ever before.

The first American Top 40 radio show aired on Independence Day weekend in 1970 with host Casey Kasem, who kicked off the countdown with the No. 40 song in America: “The End of Our Road” by Marvin Gaye. The American Top 40 wasn’t the first hour-long program based around America’s favorite songs. Legend has it that the idea for a hits-only radio syndication came from Todd Storz, the owner of KOWH in Omaha, Nebraska. Depending on the history book, Storz either came up with this idea in Nebraska or while serving in the First World War when he watched a waitress at a restaurant use her hard-earned tip money at the jukebox to play the same songs over and over again. When he asked her why, she didn’t have a reason. She just liked them. Americans, he concluded, maybe didn’t want variety and complex programs: They just wanted their favorite songs played on a loop.

Storz later commissioned a study to find out how Omaha residents listened to music, and in 1952 turned KOWH into America’s first top 40 radio station. Storz’s realization was germane in the 1940s as television became more prominent and Americans became less interested in listening to their old clunky radios. Something had to entice them to keep the dials turned. More importantly, something had to lure advertisers to continue paying to run ads on those channels. When radio networks decided to make hits-only top 40 stations, though, they still had to make decisions about which songs got played. What songs you play, after all, says a lot about your primary audience. And in radio — as with most forms of entertainment that profit off of advertising revenue — there are only two major divisors of listeners: age and race.

Radio has always divided the population into different stations based on perceived listener demographics. The airwaves were a place for everyone, and radio stations emerged to cater intentionally to different demographics, usually based on genre preference or race. The first radio station to air exclusively black performers, the All Negro Hour on WSBC, launched in November 1929 in Chicago. By 1949, WDIA in Memphis had a station with an all-black announcing staff and WERD in Atlanta was a fully black-owned station. “One of the things that a lot of people don’t realize is how important these early black radio stations were in spreading black music around the country,” Brenda Nelson-Strauss, the head of collections at Indiana University’s Archives of African-American Music and Culture, told NPR last year.

Black owned-and-operated radio networks mostly played popular black music being created at the time, notably rhythm and blues. By the end of the Second World War, these radio stations were attracting white listeners as well. “We had a bunch of white listeners to our black station, back in the day, and we would program some songs to attract them,” Herb Kent, a disc jockey at WVON in Chicago, told NPR. By the 1960s, even white stations were beginning to play black music in an attempt to appease their listeners. Black radio fueled rock ’n’ roll’s rise to popularity, and black radio still has a lot of white listeners. As of 2013 (the most recent available numbers), 21.1 percent of Urban Contemporary radio (a euphemism given to stations that play mainly R&B and hip-hop hits and cater to black audiences) listeners were non-black.

Top 40 stations benefited from plenty of rein over what they could play and featured playlists created by individual station managers that fit their areas. A top 40 station in Birmingham, Alabama, for example, might pull in a couple of songs from the R&B charts as well as a couple of songs from the country charts. A top 40 station in Chicago might pull from the R&B chart and from local charts. But by the late 1960s, stations had more standardized playlists. Initially, those playlists included high-charting black artists appropriately placed on the American Top 40 countdown.

But as black radio stations became more popular in the 1970s, many white owned-and-operated radio stations, like top 40 stations, began to distance themselves further and further from R&B. The country was beginning to divide further and further along political lines. Radio stations, long a space used for political discussion and discourse — even stations that focused on music — began to separate on these lines as well. (It is still true that Urban Radio — a name that encompasses all “urban” genre stations — has a listenership with a higher percentage of Democratic voters than any other station format.) It was in this climate that Kasem’s American Top 40 program came into being.

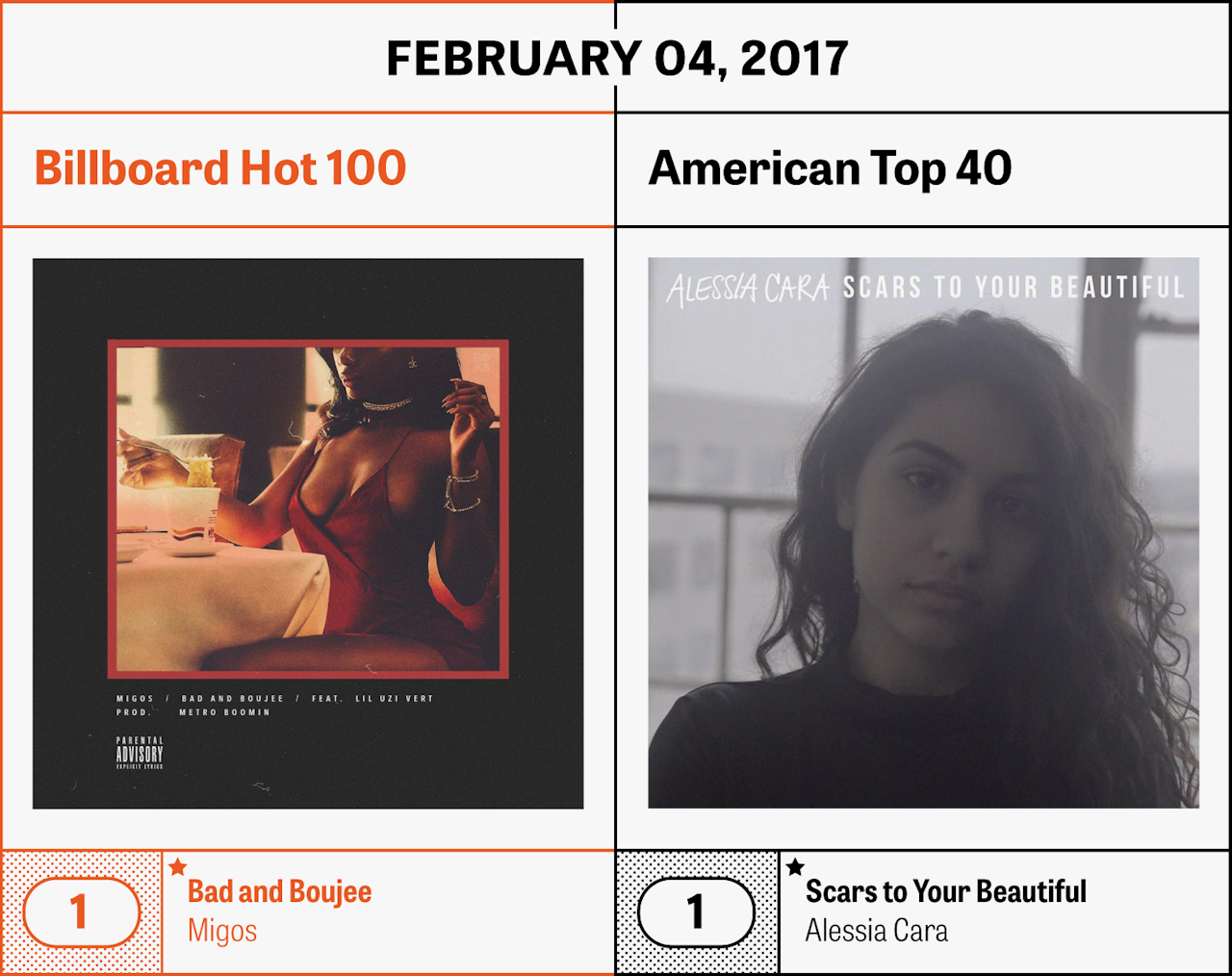

When Kasem’s American Top 40 launched, its entire ranking program was taken directly from the Billboard Hot 100 chart. During Kasem’s programming, he frequently announced that Billboard was the “only” source for his hits. Because Kasem’s program came directly from the Billboard chart, the people who bought the music determined what entered into the top 40. Because the Billboard chart (at the time) counted sales of singles as its biggest percentage, any single that sold well could find itself in the top 40 without any radio executive being able to stop it. That means that for the first episode of Kasem’s Top 40, 14 of the top 40 songs were performed by black artists. (Just for comparison’s sake: The February 4, 2017, chart used by American Top 40 had nine black artists on it. The Billboard chart for the same date had 15.)

The Billboard Hot 100 chart held incredible power over how frequently a song got played, and how much opportunity an artist had to become successful. The Hot 100 combined single sales and radio airplay, so in a way, the chart and the top 40 stations were self-referential. Radio station managers of independent top 40 stations controlled how many of the songs off the Billboard Hot 100 they actually played. If a station manager knew that their audience liked, for example, only upbeat songs because those were the only songs callers requested, they might skip over the songs in the Billboard top 40 that didn’t fit that tone. More often, though, the true dividing factor determining what got played was genre. As rock ’n’ roll became more fragmented and genres like heavy metal, dance, and new wave gained in popularity, top 40 stations were more likely to pick just one emerging genre (say dance music, for example) for their listeners. But when top 40 stations played American Top 40, the programming was the same across the board.

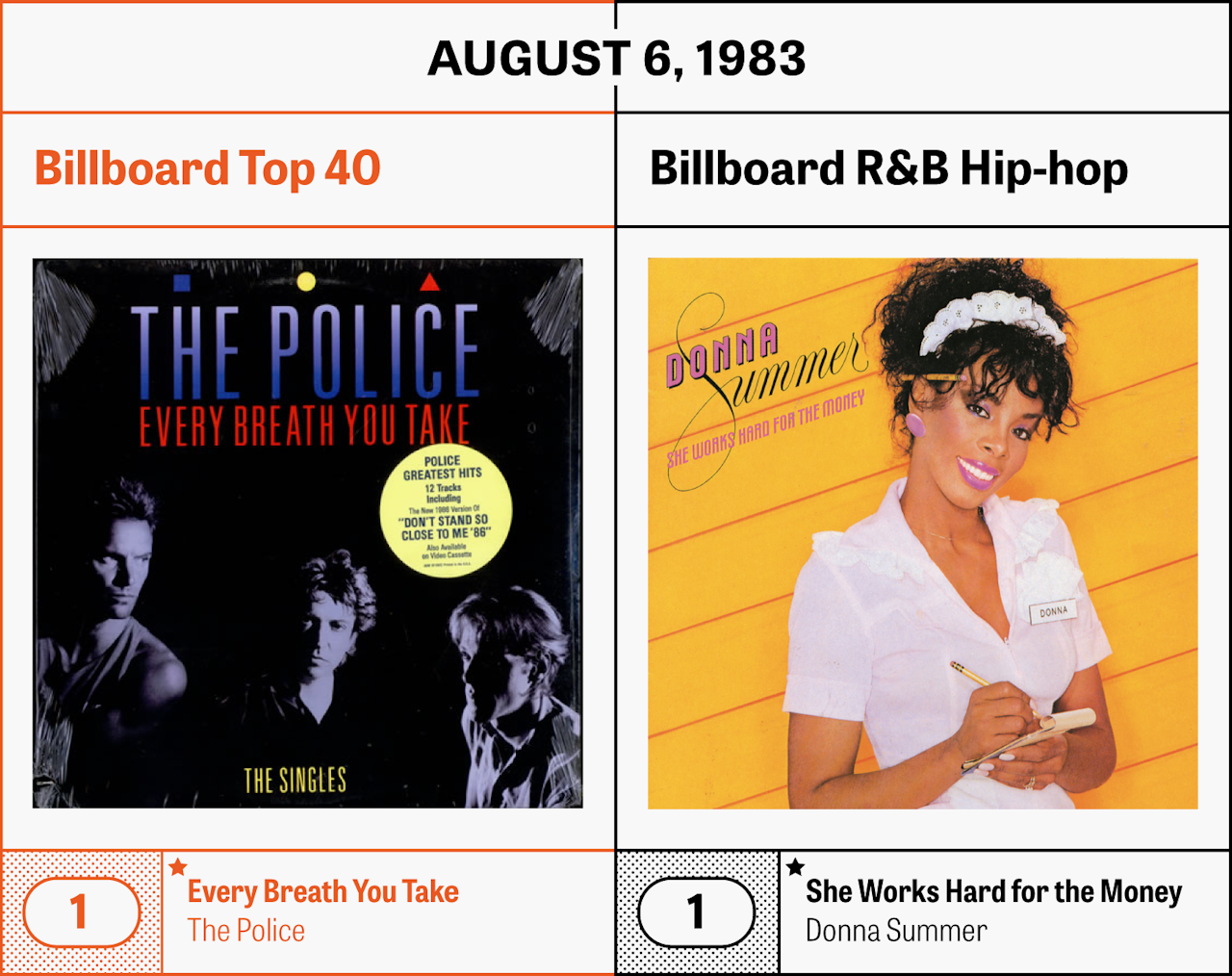

Because the Billboard Hot 100 and the R&B charts in the ’70s and ’80s were only based on two things (single sales and radio plays), any disparity between a genre chart and the Billboard Hot 100, and thus the American Top 40, would have been entirely based on either of those things. A hit that was so gargantuan that it sold enough to become No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 would get played on American Top 40 stations as well. The entire process was fairly transparent. Until very suddenly, it wasn’t.

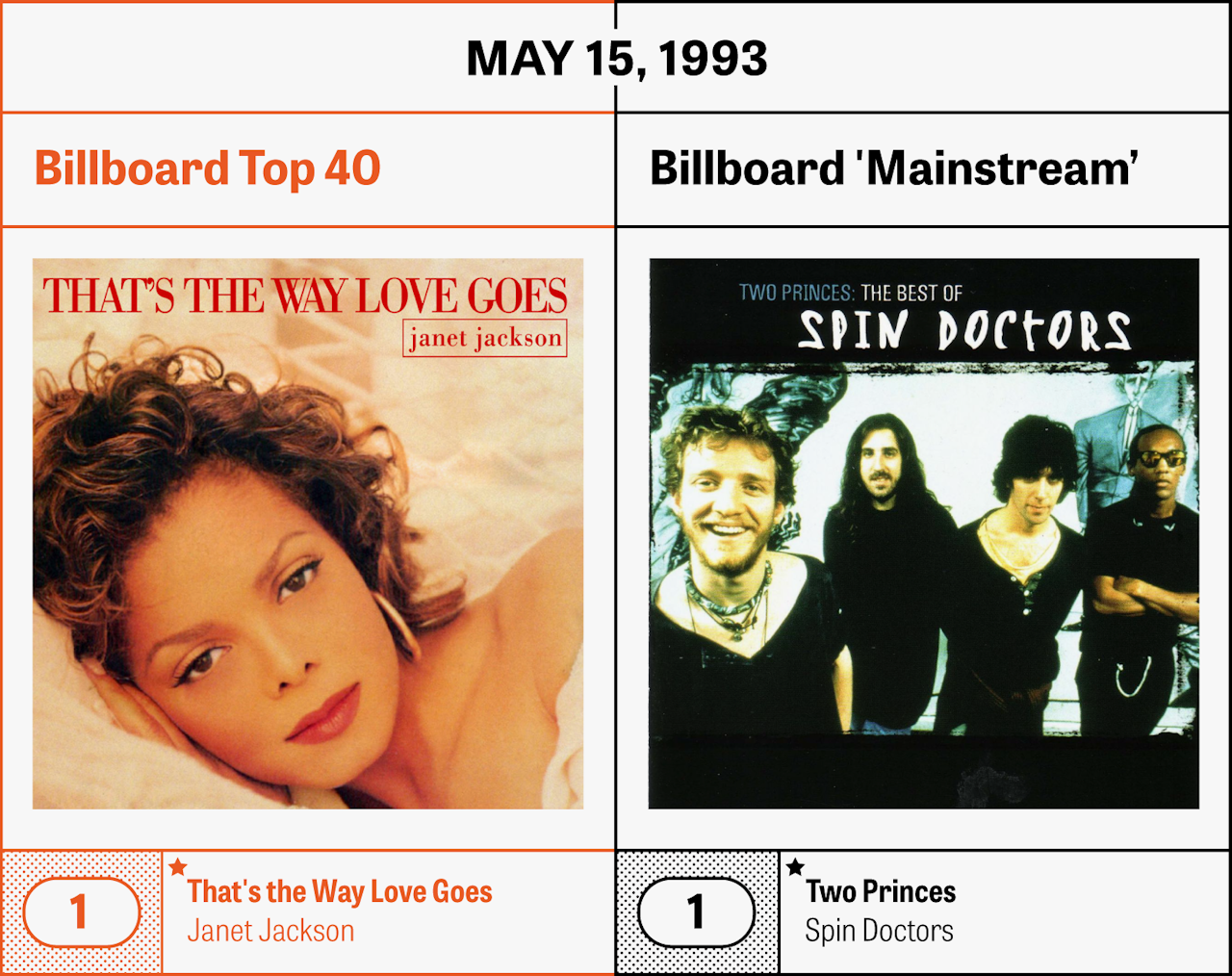

Between 1991 and 1998, the top 40 played on the radio radically changed. The advent and spread of the internet and technology set the radio business into turmoil. But the first change to the way the Billboard charts were set wasn’t to add in streams of songs or include video plays; it was to change the way played songs were reported to the magazine. Before 1991, stations manually reported song plays to Billboard. In 1991, Billboard went digital. In November of that year, it implemented Nielsen SoundScan counts across all stations and for every chart, so there was no hiding what was played and how many times. That same month, American Top 40 stopped using the Billboard Hot 100 to determine its list and switched to using the Billboard Hot 100 Airplay chart, a chart Billboard maintained that only tracked songs played on the radio. American Top 40 did not give a reason for this change, but the fact that it correlates so closely with Billboard’s switch to Nielsen counting suggests that they didn’t want consumers to control what they played on their stations anymore.

The change in charts used to calculate the top 40 also had a convenient side effect for station managers. Many of the songs that charted highly in the late ’80s and early ’90s were more erotic and too sexually explicit in nature to play on the radio because of broadcasting laws. Most of these songs, by happenstance, were also performed by black artists. Think: “Me So Horny” by 2 Live Crew, which hit No. 26 in 1989, “Cop Killer’ by Ice-T’s group Body Count, which hit No. 26 in 1992, and “The Humpty Dance” by Digital Underground, which hit No. 11 in 1990. All of these songs apparently caused such moral dilemmas for American Top 40 hosts that they refused to say some of their titles on-air, and gave them all radio edits. (In all fairness, this also happened with George Michael’s “I Want Your Sex” in 1987.)

Just two years later, though, in 1993 American Top 40 switched the chart it culled its list from to the Billboard Top 40 Mainstream chart (or the Pop chart). The Pop charts measured only the songs being played on top 40 radio stations, meaning that those stations were no longer subject to any list that they didn’t maintain themselves. The circle was complete. This allowed radio stations to control the chart they were presumably playing to show the tastes of America. Outside of countdown time slots (when the station literally counted down to the No. 1 song), the station could feature other music, which was then almost guaranteed to be a top 40 hit the next week because of the chart’s self-referentiality.

The radio business was further shaken when the FCC passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996. It was the first overhaul of telecommunications law in 60 years, and was drafted because the internet had made it clear that voice and video services could be delivered together over the internet and thus should be deregulated.

The Telecommunications Act, Weisbard told me, “completely changed the rules … It let companies like ClearChannel own hundreds of stations. When that happened, it felt like radio was becoming more cookie-cutter.”

After the act passed, ClearChannel, which owned 43 stations in 1995, went on a buying spree. By 2000, it owned 830 radio stations. In 2014, ClearChannel changed its name to iHeartRadio. The corporation consists of 850 radio stations and claims to reach 110 million visitors each month. It is the home to the American Top 40 broadcast, featuring Ryan Seacrest.

In October 2000, American Top 40, now owned by iHeartRadio as well, completely abandoned the Billboard charts. Instead it gets its music charts from a company that it owns called Mediabase. Mediabase’s chart methodology is not transparent, but it does include iHeart stations in the counting. This effectively means that top 40 stations are not obligated to play something they don’t think their listeners will like — which just so happens to be mostly songs by black artists.

If you compare the Billboard top 40 for February 4, 2017, to the American Top 40 chart for the same date, there are 12 songs that differ between them. Of the 13 different songs on the Billboard chart, seven of them are songs by black artists that have never appeared on the American Top 40 chart before. (One of them is a country song, and the other four are 2016 hits by white artists.) Of the 12 songs that replaced them on the American Top 40 chart, only two of them (“Do You Mind” by DJ Khaled featuring Nicki Minaj and “Cold Water” by Major Lazer featuring Justin Bieber) were performed by black artists. The Billboard chart for that date is 40 percent black artists; the American Top 40 chart, 17.5 percent.

But unlike in previous decades where top 40 stations might have syndicated American Top 40 and then adjusted the rest of their airtime for their listeners, today, the majority of top 40 stations now are syndicated iHeart stations. iHeartRadio did not respond to requests for data. Fewer and fewer cities have their own top 40 anymore, much less their own DJs. On a Saturday, you can drive through several states without ever losing the signal for iHeartRadio’s top 40.

According to Nielsen Music’s report on 2016 music, only six of the top 40 songs played on the radio over the course of that year were performed by a black person. Only one song by a black person placed in the top 10: “One Dance” by Drake featuring Wizkid and Kyla, which came in at No. 2. The Billboard Hot 100 songs for 2016 featured twice as many black artists: 13 songs made the top 40, and three of them were in the top 10.

Many of these songs reached their heights because the Billboard charts have, since 2007, included digital downloads, streams, and video plays in their calculations — three things the radio’s top 40 doesn’t include. While a song might get popular enough on a streaming platform to nudge the hand of a studio manager at a top 40 station, the data seems to show that more often than not, equality does not reign on American Top 40.

Simply put, the outdated and closely controlled ways of the top 40 allow for systemic musical segregation. Dance hits by white artists are played every hour on the hour on top 40 stations even if the No. 1 song in America (this week it’s “Bad and Boujee,” by Migos featuring Lil Uzi Vert) never gets a single spin. It’s no longer America’s top 40, unless the only America you see is one that’s white, high-BPM, and pretending that absolutely nothing is wrong.