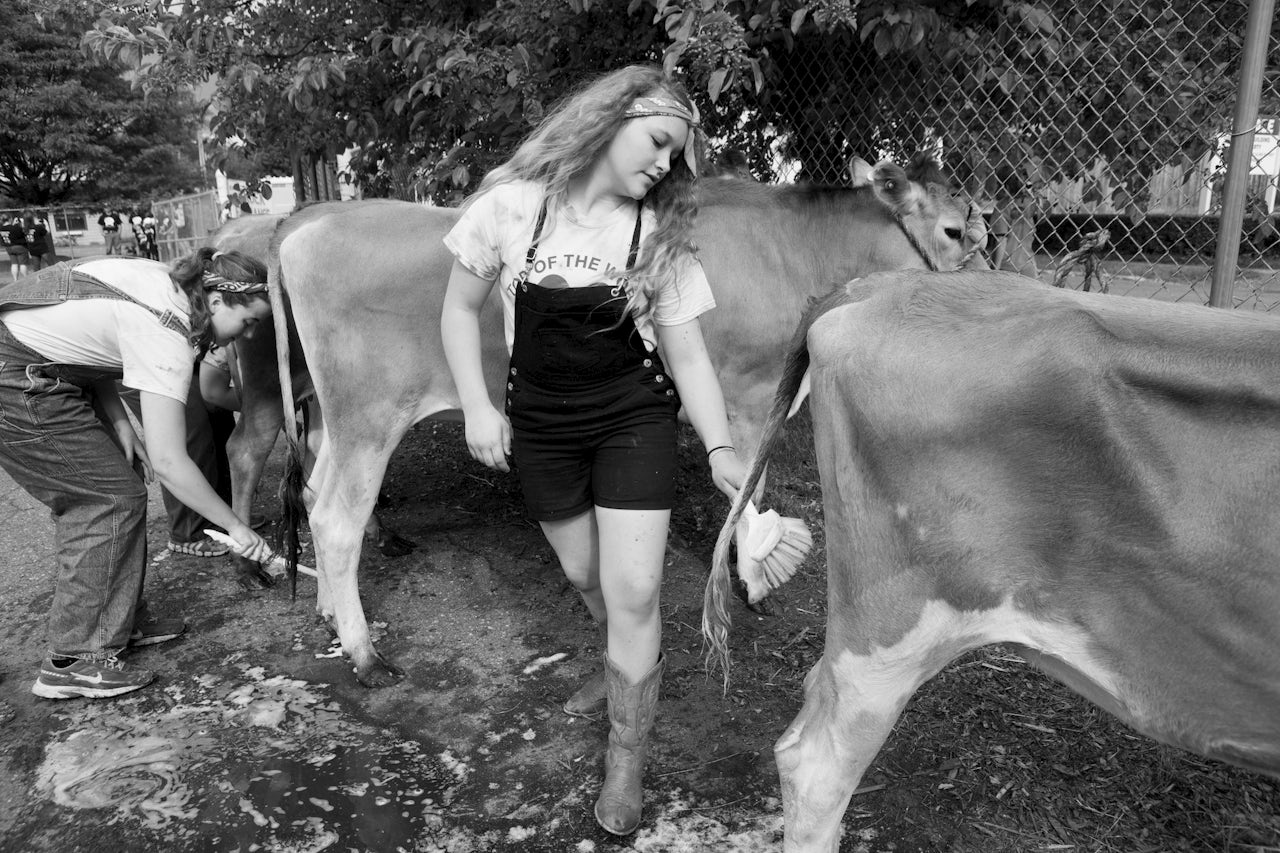

Should recent college grads seeking financial independence toss their MFAs in favor of manure spreaders?

According to The Upshot, “almost half” of 22- to 24-year olds get by with a little help from their parents, receiving thousands of dollars a year to keep up with bills and rent. Predictably, creative types living in expensive coastal cities siphon off the most familial cash. But one of the findings is surprising:

The choice of career path matters. Those in the art and design fields get the most help, an average of $3,600 a year. People who work in farming, construction, retail, and personal services get the least.

Construction? Okay, that seems like steady work, with good union rates. Retail can be cushy at the right stores, when commissions and discounts come into play. “Personal services” seems to cover everything from full-time babysitting to selling pharmaceutical-grade MDMA at Burning Man. But farming, while undoubtedly a backbone of the American economy, is still largely a run by generations that pre-date the moon landing.

Everything would seem to count against the millennial farmer, a profession that sounds culturally oxymoronic. According to the last Census of Agriculture, only 6 percent of principal farm operators are under 35 (the earliest qualifying birth year for millennial membership, while debated, is often cited as 1982). The average age of farmers nation-wide continues to increase, currently hovering around 58. Land is expensive and most 20-somethings who don’t inherit family property can only afford to rent.

Like most recent graduates, newbie farmers are often mired in student loan debt (not necessarily from farm-related studies, although demand for agriculture degrees is growing). Banks consider them a risk, and even with the explosion of urban CSAs and pricey farm-to-table restaurants, income is wildly unpredictable. While they may not receive the same monthly buffer checks as an editorial assistant living in a Brooklyn loft, these young agriculturists aren’t necessarily pulling themselves up by their root vegetables, either.

“I own the farming business, yet my parents still own the land,” says Chris Grant, 26, of Grant Family Farm in Essex, Massachusetts. “My phone is still on their plan, and I pay them for it monthly.” Many other young farmers also accept help from relatives that doesn’t necessarily come in the form of a blank check. A recent article from US News & World Report about the (slight) rise in millennial farming focuses exclusively on second-and third-generation farmers who are taking over their family businesses, pushing trendier organic products, or using their technological know-how to improve business. They aren’t taking money for rent because they are literally living off the land.

Many other young farmers also accept help from relatives that doesn’t necessarily come in the form of a blank check

Some millennials buy farms with their own money, but most who can afford to go that route have the capital (examples include the inventor of Google Alerts, now an almond farmer in California, or the NFL star who learned how to grow crops on YouTube). Articles with titles like “Forget Banking, Become a Farmer” assume that the bespoke-suited reader with secret dreams of tractor-driving already has a banker’s income.

For would-be farmers with no family inheritance or career in finance to fall back on, there is The National Young Farmers Coalition (fresh-faced like its members, founded in 2010), a non-profit that promotes debt-relief and support for first-generation farmers — a group they call “farmers by choice.” There’s even a bill idling in Congress, the Young Farmer Success Act of 2015, that would redefine farm work as a public service job so as to take advantage of the public service employee loan forgiveness program.

In other words, while the survey quoted in the Times might be misleading — farming isn’t necessarily more lucrative for 20-somethings than any other career — there is hope.

Agriculture is quickly becoming a growth industry by necessity. With hundreds of thousands of baby boomers aging out of farming in the next few decades, someone is going to have to take over. Organic farming in particular is on the rise, with an average age just inside the upper range of Generation X. And if other industries are any indication, millennials will be nipping at their dirt-covered heels.