Though I’m loath to give my parents the satisfaction, I now regret refusing the prayer rug they suggested I take with me to college. Growing up Muslim had taught me that belief was not for me — I knew I wasn’t going to pray regularly.

I haven't prayed since 2012 and yet, recently, I have found myself wanting a prayer rug, a small carpet laid on the ground during the daily ritual of salah. I’ve been perusing websites like Alibaba and Islamic Place, where you can pick one up for $20 or so. Even if I’ll never pray on one again, I get a visceral urge to touch one with my own hands, like I did as a child.

It was the graphic novelist Reimena Yee’s The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya, a story of a carpet merchant who is turned into a vampire, that reignited my love for carpets. Though the carpets featured in Yee’s novel are from the 18th-century Ottoman empire, I yearned for a more modest example: the machine-made prayer rugs I had begrudgingly prayed on my entire life. They reminded me of home, which means — for someone who moved around as much as I did — that they feel like family.

My parents are Gambian, and both of them remember that the types of 10 dalasi machine-made prayer rugs I grew up with first appeared in the mid-’70s, quickly becoming ubiquitous. Before that, they had prayed on dried goat and sheep skins. Mass-produced carpets could be found in the markets of major cities like Banjul, the capital of the Gambia; otherwise, the most common way a Gambian could get their hands on one would be as a gift from a pilgrim returning from Hajj.

The mass market rugs fit a genre. They are usually made of wool, cotton, silk, linen, or polyester — I’m most fond of cotton. They vary in color and ornamentation but almost all have an inner and outer border, a depiction of a mosque (especially Masjid al-Haram in Mecca), and an arch in the center representing mihrabs (niches in mosques that point towards the Kaaba, the shrine in Masjid al-Haram's center). They aid in prayer, primarily by separating the worshipper from the unclean ground, but these design features are also meant to help focus the mind during communion with God. With its flattened architecture, a prayer rug is a “portable mosque.” In a sense, it is a virtual reality technology, creating a three dimensional structure along its edges.

It may seem counterintuitive to describe a tradition dating to antiquity in such modern terms, but the production and use of prayer rugs is as much of its time as any cultural commodity. In both Sunni and Shia hadith collections, it is recorded that the Prophet Muhammad used a mat while praying, so we know the tradition dates to the 7th century. Yet the mass production of prayer rugs has now evolved to include recent technological elements. The modern Muslim can pray on a more interactive and adaptable device — a smart rug, essentially.

Take Niyya, the Brooklyn-based company that calls itself a “Muslim lifestyle brand,” which sells products that would not look out of place at Urban Outfitters. Though their rugs, which are named after concepts related to prayer — salah, sabr, tahara — have modernized designs, they include niches to “evoke familiarity.” The company’s main innovation is a new form of portability. Instead of folding or rolling up a Niyya rug, the Muslim on-the-go might choose to wear it as a shawl or a skirt while commuting or relaxing. On its website, Niyya models lounge on the beach, praying and then wearing the sandy rugs on which they just prayed.

One of Niyya’s stated goals is “to have people from different walks of life use the same product for what they dictate as important.” What this means, I think, is that they intend for non-Muslims to use their prayer rugs as clothing, decoration, or ornamentation. But while Niyya considers what they’re doing new, non-Muslims have long used carpets manufactured by Muslims. The most impressive carpets from Muslim-majority areas have appeared in museums, galleries, and paintings in the West for centuries. Hell, remember when Trump used a magically non-existent one as propaganda?

Border rancher: “We’ve found prayer rugs out here. It’s unreal.” Washington Examiner People coming across the Southern Border from many countries, some of which would be a big surprise.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 18, 2019

A company like Niyya markets itself as offering the only unique advances in an ancient tradition, eliding that tradition’s history. But instead of bridging cultures, Niyya may have merely turned prayer rugs into Oriental carpets. As the University of California-Berkeley professor Minoo Moallem explains in Persian Carpets: The Nation as a Transnational Commodity, “Oriental carpets are boundary objects separating the East and the West, domesticating the East and subordinating it to the spaces of consumerism in the West.” Even a religious artifact serves a different purpose when used as an exotic decoration.

In 1610, Ahmed I, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, proclaimed that rug sellers and weavers found to be selling prayer rugs to non-Muslims ought to be put to death. However much chill the Sultan clearly lacked, and seeing as I still identify as culturally Muslim, I can relate — slighty. I can’t help but find it unnerving to see these sacred objects, charged with meaning, taken out of context by startups.

Another prayer rug update, My Salah Mat ($70), touts itself as the first interactive prayer mat for children. Instead of learning through osmosis and the reproachful grunts of my elders like I did, the modern Muslim child can press buttons to learn how, and why, Muslims do each part of the five daily prayers. But though it is advertised for all Muslim children four and up, the product may not be completely universal or accessible. It omits mention of some Shi’i-specific prayer differences, like the usage of a small clay disc (turbah) that the forehead touches during prostration, so it is clear that My Salah Mat is marketing to the Sunni majority. I asked Sundus Jaber, a Muslim chaplain with a background in speech pathology, whether the mat serves as an effective educational tool. She said that the My Salah Mat could use some improvement. Its cluttered design, distracting variety of colors, and small font might make it overstimulating to children with ADD, ADHD, autism, or other special needs.

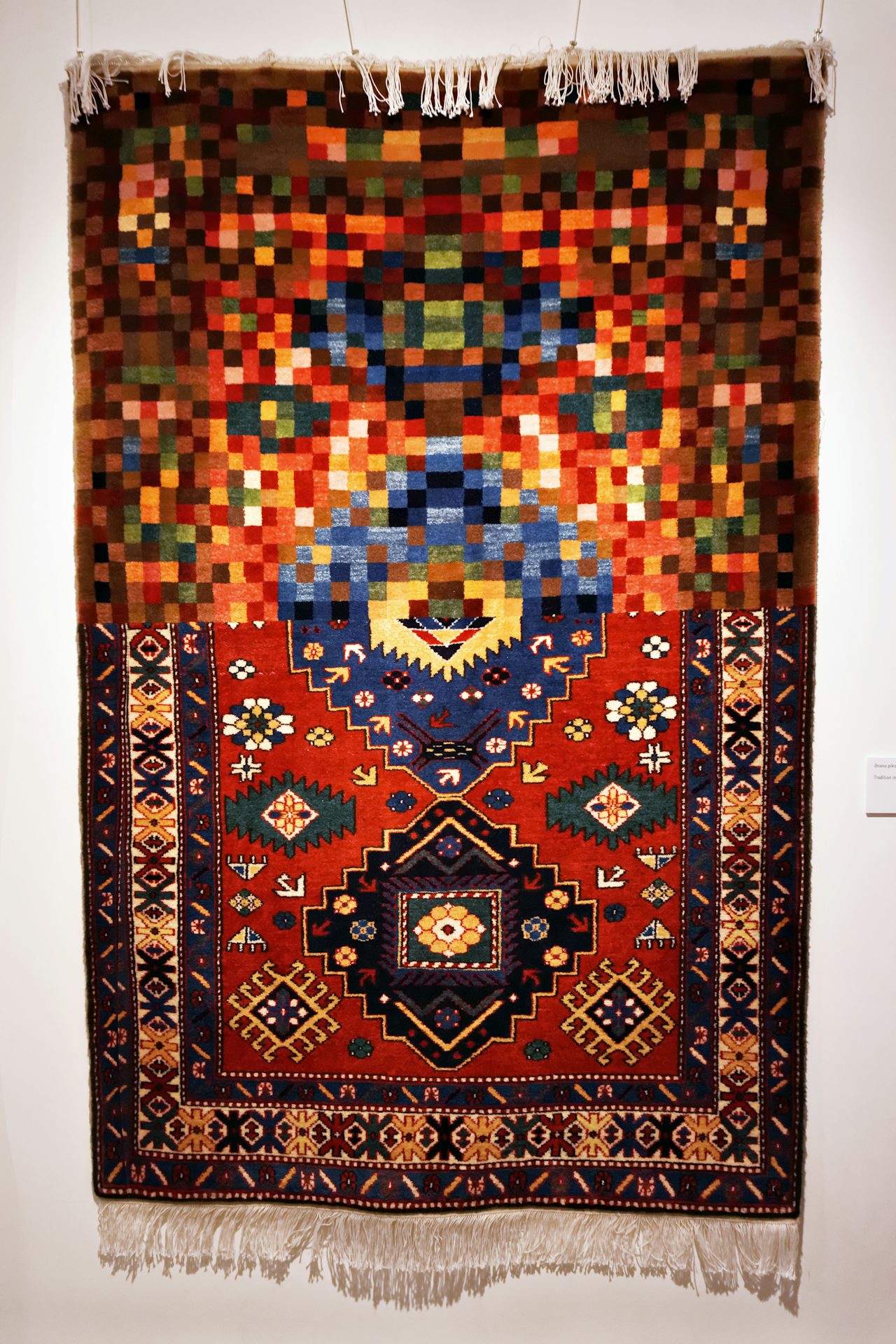

Still, I can imagine my niece — who gets rather upset that I don’t pray while she has to — spending hours with what amounts to an Islamic gaming console. But it is a misnomer to call My Salah Mat the first interactive prayer rug. Muslims have interacted with their rugs for centuries. Because the compact fibers of machine-made rugs form a smooth surface, it’s easy to draw on the carpet by rubbing a finger with or against the grain, creating a dark or light line. These drawings can play off the geometric structures already present on the rug, or add new shapes. Some carpets by contemporary artists Saks Afridi, Alia Farid, and Faig Ahmed incorporate this kind of material addition and distortion.

When my family lived in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, we would walk to a nearby mosque for Friday prayer. The carpet was a dark green and had golden rows of niches side-by-side. I would draw on it during the imam’s sermons, of which I understood nothing, even though he translated it into English for the non-Arabic speakers after prayer.

I particularly loved to combine shapes. My greatest creation — novel to my eight-year-old mind — was a new type of star, comprising two intersecting triangles, with six points. I remember looking around, secretly hoping that someone would marvel at my invention. The only attention I received was from an old Arab man who glared at me until I erased it. Later on, I realized that he was probably upset because of the star’s presence on the flag of a certain other Middle Eastern state.

The old man had a noticeable prayer bump on his forehead, caused by years of friction against various carpets. My parents both have them now too. I’m still getting used to the idea that prayer and faith can change the bodies of my loved ones.

It is this kind of effect that the TIMEZ5 prayer rug, which retails for $300, is meant to mitigate. The TIMEZ5 rug’s claim to fame is that it will not only relieve you of back and joint pain caused by the repetitive standing and kneeling entailed in Islamic prayer rites, but improve your posture and energy levels with its five layers of material. One of these layers uses NASA-certified antibacterial technology — an apt connection since, as we all know, Muslim astronomers invented space. While medical professionals based in the rug’s major market, the UAE, have cast doubt on some of its claims, some users are in agreement that it can provide relief for the joints, especially those of older Muslims.

But TIMEZ5 too relies on the language of innovation at the cost of a basic grasp of technological history. “We used space technology to disrupt an industry that hasn’t innovated in 1,400 years,” the founder says on the NASA Spinoff website. This formulation ignores the fact that, for some time now, carpets and rugs have been woven on automatic looms — a technology that dates back to the late 18th century.

There is more practical utility in rugs like those produced by I&J Innovations, which range from $15 to $20, and have attached sensors. When your forehead depresses the sensor, it notes that you have completed a ra���kah (a single unit of prayer). In the future, perhaps I&J Innovations will integrate the posture-identification technology developed by Kasman Kasman and Vasily G. Moshnyaga into their rugs. The new technology might help those who, for whatever reason, can no longer keep track of what prayer step they have just completed.

However innocent the rug’s intention, it’s clear that it could also be used as snitch technology. Say your grandmother asks you to go pray maghrib, the sunset prayer. In the past, a child might rush through ra’kahs like God gave extra marks for speed. Children in the future might be marched right back to the rug if their ra'kah counter shows that they haven't prayed perfectly, or long enough.

And like most technology, there’s also a nefarious possibility here, like the numerous ra'kah recording apps that store a record of your prayers in the cloud. From Islamophobic states keeping track of which Muslims pray, to Islamist ones noting which don’t, the prayer rug of the future could also be a restrictive tool of the state.

Perhaps most dazzling of all of the new products is EL Sajjadah, the LED prayer rug. It sets out to answer a question all Muslims face when beginning a prayer: Which way is Mecca? Taking inspiration from rugs embedded with analog compasses, the unsuccessful Kickstarter project (which raised $47,128 of its goal of $100,000) used a digital compass and glows when oriented towards the Kaaba. It was exhibited in New York’s Museum of Modern Arts, cementing it as a piece of art and not a true prayer rug — a sacred object that has artistic elements but is, ultimately, a ritualistic device.

Whether or not these updated prayer rugs sell, their functions are not so unrelated to the age-old form, bound up as it is in the directional and communal practice of prayer. Such are qualities I’ve experienced personally. When we lived in Saudi Arabia, my parents drove us to Mecca and Medina for Hajj. I cannot recall my exact age. We were praying at the Prophet’s mosque, on carpet I remember being burgundy and green. I don’t know how, exactly, but — mind still whirling from circumambulating the Kaaba days earlier — I wandered away from my parents. As often happens at mosques, even in the Prophet’s city, my flip-flops had been stolen. My naked feet found their way onto the veined marble of the courtyard that had been made blistering hot by the afternoon sun.

I walked for what felt like hours. With each step, the mosque grew in size and the rush of people increased.

Eventually, I met a guard. Seeing me hopping from foot to foot, he left his station and handed me a pair of black flip-flops. They were too big, but it didn’t matter — I was overjoyed that the soles of my feet were no longer on fire. I don’t quite remember how, but I was returned to my family.

I rejoined them on the carpet. Its touch cooled my raw feet. I was home.