A few weeks ago, as activists were busy barricading themselves inside of Garland Hall, an administrative building on the campus of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, they were also rushing around, scraping up a few bucks for bus fare for someone who had come and was sympathetic to their cause.

This was May 1 — May Day. For nearly a month, the organizers, including among them students and Baltimore residents, had been occupying the building, in which the offices of the president, registrar, student finances, and other administrators at the college are all located.

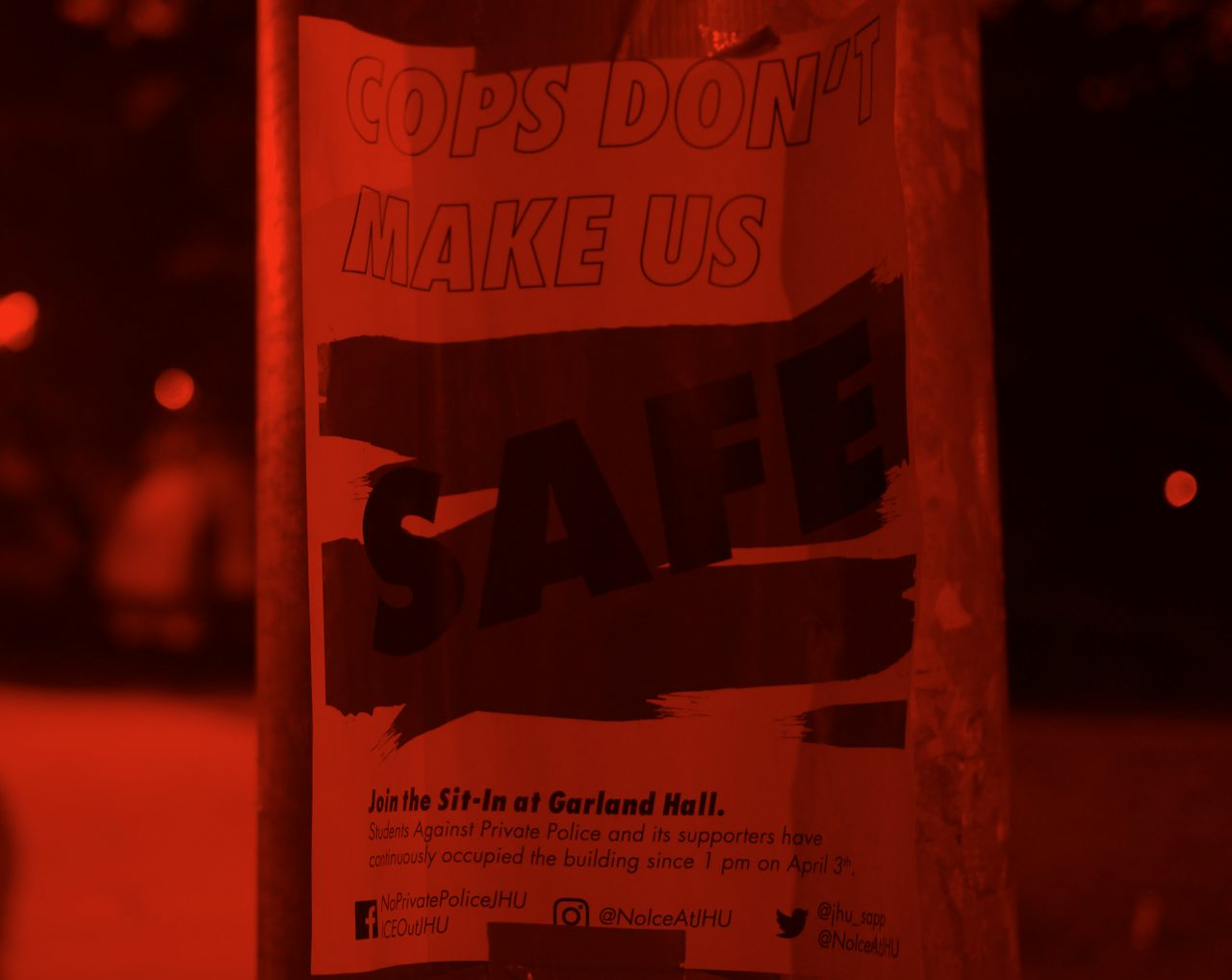

They had taken over Garland Hall, situated inside the bucolic campus of a school where the undergraduate tuition starts at $50,000, to protest the university's proposal to create its own armed private police force, as well as its million-plus dollar contracts with Immigration & Customs Enforcement. But it was also important to make sure anyone who showed up to support their efforts got home easily and safely, even amid what they had declared as the final “escalation” of their month-long action. Facing likely arrests, this was still about community.

Before too long, Hopkins’ president, Ronald Daniels raised the stakes, threatening suspensions or expulsion of any students inside the building. About a week later, when those warnings did not entirely shake the occupiers, the inevitable occurred.

On the morning of May 8, nearly 100 Baltimore police officers surrounded Garland Hall and a small squad sawed open the chains and crashed through the glass door. The protestors sang the folk song “Solidarity Forever” as police broke inside, screamed the Assata Shakur Chant (“It is our duty to fight, it is our duty to win...”) as they were warned to disperse one last time. They streamed the incident on Facebook Live until the five remaining activists inside were dragged off in zip-tie handcuffs, all under arrest.

When one of the arrestees, a trans woman named Opal Phoenix, was placed in a police van for male-identifying detainees, two students dropped to the ground and placed their bodies inches away from the van’s tires. The cops guffawed, and arrested them too. (A statement from police after the fact said in part, “We are currently reviewing the incident in its entirety to determine if corrective actions are needed.”)

If you wanted a case study in the stakes of campus politics, and how conservative talking points about millennial apathy and/or entitlement are clearly in bad faith, a group of students who attend a prestigious university performing a sit-in for almost a month and fully taking over a university building for a week — risking arrest and their own safety — is a pretty good one. This was real political work and organizing, nothing like the picture painted by stodgy columnists in which campus protests stem from primarily petty, illiberal complaints about having one’s feelings hurt. For these students and the Baltimore residents with whom they worked closely, this was about potentially saving lives.

“Police do not make anyone — especially black people — safer. A private police force would only increase the harassment of black people as long as that police force exists,” Cyril Creque-Sarbinowski, a graduate student involved in the sit-in since the beginning, who has also been organizing against ICE’s presence on campus for over a year, told me. “As a black person, I do not want to see other black people be further abused and harassed and will take action in order to prevent that from occurring.”

In early 2018, representatives in both the Maryland State House and Senate introduced a bill that would private universities such as Johns Hopkins to create their own police forces, whose officers would have both guns and arrest powers. Given that Hopkins, which was clearly the motivating force behind the legislation, has large campuses on each side of Baltimore, with plenty of property through the city as a whole, the creation of such a force might have the potential to span much of the city.

The practice of private universities maintaining their own private police forces is common around the country — and, as evidenced by the uproar caused when campus police at Evergreen State successfully petitioned to obtain assault weapons, often controversial. However, there are no such campus cops in Maryland, only conventional police departments which operate at public universities. In Baltimore, university cops have become notorious for malfeasance and worse, alongside the city's hopelessly corrupt police department. In 2013, police officers at Morgan State University — a historically black college not far from Hopkins with student body of around 8,000 — along with Baltimore police officers stopped a 44-year-old man named Tyrone West, tasing and beating him when he tried to flee the scene. He died in police custody shortly thereafter. In 2015, an officer employed by Coppin State, an HBCU with a student population of nearly 3,000 — shot and killed a teen named Lavar Douglas. (Douglas’s death and the lack of transparency about it were the subject of a 2018 episode of The New York Times’s podcast The Daily ).

Students and residents marched in protest upon learning of the bill’s existence in March of 2018, and their vocal opposition effectively killed the bill wholesale. Activists warned of future incidents like the killings of West and Douglas and stressed that a city that spends nearly $500 million a year on law enforcement didn't need more police. “We’re not gonna just let you like, pop bills up on us in the middle of the week and think that you're gonna get something passed,” Karter James Burnett, a junior at Hopkins who helped lead the march, told me after the demonstration last year. “People always equate more cops and more police with becoming more safe but that's not always the case — especially when you're in one of the most corrupt police states in the country.”

Around the same time as anti-private police sentiments grew, members of the Hopkins graduate workers union, Teachers and Researchers United (TRU), began calling attention to the university’s million-dollar contracts for leadership training for employees of ICE. Hopkins professor Drew Daniel started a petition demanding the school end the contract.

Hopkins continued pushing for the private police force in the next legislative session in February 2019, this time with a bill sponsored by state delegate Antonio Hayes, a Democrat from Baltimore City, and endorsed by, among others, then-mayor Catherine Pugh (who, following an FBI raid on city hall, has since resigned and also accepted donations from nine Hopkins officials) as well as former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, a Hopkins alumnus who months earlier had gifted the university $1.8 billion. The new bill was larger and more complicated, boasting of its oversight in contrast to the corrupt police department, and renamed “The Community Strengthening Act.” It passed in March with three of six state senators and seven of 11 house delegates voting for it.

Hopkins did not budge on its ICE contracts either. “We have been unequivocal in our public statements concerning the consequences of recent immigration policies that have a clear, direct and demonstrable impact on members of our university community,” a university statement issued in response to calls to end the contracts read in part. Those opposing private police and ICE contracts on campus already shared politics — the same people often petitioned or marched against both — and once the private police bill was essentially a done deal (Maryland's Republican Gov. Larry Hogan signed it into law last month), they joined together “against campus militarization” and began the sit-in.

The sit-in was supposed to last only a day, organizers stressed — they assumed at the end of day one they would be carted away by cops or kicked out by security. Primarily, they wanted the attention of Hopkins President Ronald Daniels, a former lawyer who, despite having stressed the need for “sustainable safety changes” at Hopkins, has nevertheless pushed for an increased police presence on campus due to what he perceives as the “brazenness” with which crimes are committed. Daniels met with two students on day one of the sit-in, told them that the private police force was a done deal, and said they could consult on the specifics of what the police force would look like if they liked, in exchange for stopping the protest.

Alternately driven by determination, frustration, and spite, the sit-in continued. Administration continued working in Garland Hall with sleeping, studying, and chanting students surrounding the first-floor security desk. Administrators, including Daniels and Provost Sunil Kumar, walked up steps that were draped in a banner reading “NO PRIVATE POLICE, NO ICE CONTRACTS” and past students demanding they talk to them about private police and ICE.

“We began to transform Garland Hall into a space that actually served students and community. The sit-in created gender-neutral bathrooms, held morning group stretches, offered free coffee and food for all, as well as free bathroom supplies,” Ph.D student Rasha Anayah told me.

Above one entrance to the building a banner declared, “El Chingas Fascismo” (loosely, “the fucking fascists”). Next to it, there was a goofy cartoon illustration of Ronald Daniels saying, “Fuck Private Police.” A robust list of “Community Agreements” were posted, telling occupiers “no alcohol, no smoking,” and declaring that they shouldn’t “let non-CIS men do all the feminized labor.” They played a lot of Drake and hosted a few dance parties. They cleaned up each morning, methodically moving all of the furniture off the carpets, vacuuming, and cleaning up the night’s trash and recycling.

“I helped clean Garland — bathrooms, floors, tables, etc. — so that the space was as nice as, if not better than, it was when we entered,” Creque-Sarbinowski told me.

Weekly marches against private police and ICE ended in Garland Hall with free food, dropped off by sympathetic community members or ordered by the organizers using donations they received from a GoFundMe drive that earned over $12,000. More people showed up, and the group went from around 10 people to at times nearly 30 sitting-in overnight.

“We operated under a horizontal and democratic structure where each person’s input regardless of the length of time they were committed to the struggle was weighed equally,” senior Marissa Varnado told me.

There were screenings of films such as Battle of Algiers and, Losing Ground, and a small library was created, featuring copies of books such as Mumia Abu Jamal’s Live from Death Row, Assata Shakur’s Assata, and Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. There were teach-ins with subjects “Tatreez: The Art of Palestinian Embroidery,” “Minorities and the Law in Pakistan,” “How South Korea Impeached a President,” and “Algeria’s Hirak Movement.”

“I occasionally threw out trash and provided Korean sheet masks for skin care, but it was part of a collaborative effort with the larger group, not something I ever did alone,” graduate student Sungmey Lee told me.

Chris Bilal, an East Baltimore resident who until late 2017 had been working in New York City advocating for police reform, stressed to the students the deeper lessons from years of organizing. Hopkins’ private police would be in his neighborhood of Washington Hill if the bill passed, and he had seen how the university had slowly developed and gentrified his part of Baltimore.

“So, I come home and I find out that Michael Bloomberg has given a $1 billion to Hopkins and he supports a private police force,” Bilal told me. “He had been the mayor of New York during Stop and Frisk, right? He was like one of those guys off Scooby Doo, like, ‘I would have gotten away with it if not for those meddling kids.’ Now he’s testing those plans in Baltimore?”

Bilal began reaching out to groups such as the ACLU and setting up meetings with the politicians who would vote on the bill. He also helped reach out to the family of Tyrone West. West's sister, Tawanda Jones, had been gathering in memory of her brother every Wednesday since his death six years ago and to her, what a university police force can do to Baltimore residents is exemplified by her brother Tyrone.

“Hopkins want to say they want to use Morgan State as an example? Well, let’s use it as a goddamn example,” Jones said.

Along with “no private police,” and “end the ICE contracts,” the sit-in had a third demand: “Justice For Tyrone West.”

A few weeks into the sit-in, Hopkins contacted West’s sister Tawanda Jones and warned her that, if she returned to Garland Hall, she would be trespassing. In response, sit-in organizers took over a conference room in Garland Hall, renamed it the Tyrone West Wellness Center, and declared it a “safe space,” which for them meant a place to sleep or escape both security guards and the security cameras recording the lobby. They also used the building to plan the escalation of the sit-in. Students walked out of center’s room in chains with megaphones and told security and faculty they were now “fully occupying” the building.

The day-to-day of the sit-in was largely unchanged after the lockdown — teach-ins and other events still happened — but the reaction from Hopkins administration became markedly different. The university called the students’ parents and told them their students may endure serious academic sanctions or even expulsion for the occupation. Security cameras were installed on the lights surrounding the exterior of the building. There were multiple false alarms and fears of a raid — all in the name of residents’ and students’ “safety.”

“What started as a strong expression of disagreement with university positions and policies has since been dramatically escalated by the protesters and now involves a number of serious health and safety issues,” a May 3 statement from Daniels said.

For many, this pressure worked, and students began to pull away. The university reached out days before they called the police on the occupation and said they would negotiate but the details were vague. The occupiers were suspicious.

“The students had been trying to get a meeting with Hopkins officials for about year and a half now,” Bilal told me. “We also wanted to structure those meetings our way because power is maintained by setting an agenda, [and] we were pushing back against that.”

They asked for a meeting that would be livestreamed for “transparency” on May 5. They did not get that. One day before the police entered Garland Hall, the demonstrators received a letter from Daniels and Kumar. “We fully recognize the strength of your conviction to issues that are important to you, but believe that repeatedly restating an entrenched position on the occupation makes forward movement virtually impossible,” it read in part. Later it said, “We are offering the extraordinary step of extending amnesty to protesters who are willing to end the occupation.”

Students saw the letter as both a threat and a sign the university was afraid. They sent a letter back with a few proposed meeting times and received no response. Then the police came.

The most bizarre moment came the afternoon before the raid. Daniel Povey, an assistant professor and speech recognition researcher, stood in front of Garland Hall holding handmade signs that read, “Enough With The Progressive Bullshit” and “Don't Make Me Tell Your Mom.” His main beef, he told me over email, was that servers housed in the basement of Garland Hall would eventually need to be physically rebooted and that Hopkins administrators had failed to adequately provide him a timeline for when he would be able to access the building again.

“I don’t have much sympathy for their political stance. But fundamentally I was not interested in arguing the politics or staging a political counter-protest — it was clear to me at that point that they were going to lose anyway,” Povey wrote. “I was just losing patience with the disruption to everyone’s lives from shutting off the building, rather than just occupying it.”

That night, Povey, with bolt cutters in hand, approached Garland Hall with a small group of people — some of whom he said were “homeless” people from the area — and forced his way into the building during a moment when the organizers unchained the door so some people could temporarily exit. A fight ensued inside and spilled into the area outside Garland Hall. Hopkins’ security watched and did not intervene.

According to a letter from Hopkins administration provided to me by Povey, he has been placed on administrative leave with pay, and an investigation into his conduct is pending. When I asked Hopkins about Povey’s administrative leave, spokesperson Jill Rosen told me, “We cannot comment on individual personnel matters,” adding that, “We can confirm we have taken interim actions.”

In the aftermath of the raid, activists found the Twitter account for Chris Warren, one of the arresting officers. It included some telling messages. “Found a painting I would hang at work but it might melt a snowflake,” one tweet read, with a photo of him posing in front of a painting of Clint Eastwood as Dirty Harry. Another tweet, posted 11 days into the sit-in, read, “How can anyone be a cop on college campuses these days.? [sic] God what a terrible generation.”

The morning raid itself in which the university called in the police, who showed up 100-strong, had proven the sit-in’s points about police militarization. A Hopkins professor entering the building with bolt cutters and a cop talking like a Twitter troll made it even scarier (not to mention extremely online).

Yet, two hours after the raid, organizers who had not been arrested held a press conference for media, intent on being understood. Turquoise Baker, a political science major at Hopkins, read a statement off of her laptop as dozens of cops still milled about the campus.

“Students and community members have engaged in a peaceful protest for 37 days. Since April 3, 2019, the Garland Hall sit-in, which escalated into an occupation on May 1, is a final stand to demand Johns Hopkins University immediately stop the creation of a private police force, ends its contracts for Immigration and U.S. Customs Enforcement, and actively push for justice for Tyrone West and all victims of police brutality,” Baker said. “This is an effort to protect black, brown, queer, and all marginalized people who Hopkins is actively endangering.”

They then opened up the press conference to questions.

“Please take this question in the way it is intended, I'm neutral, I'm somewhat ignorant at times,” a local TV news reporter began. “Why do you care enough to be threatened with arrest and expulsion from this?”

Karter James Burnett, who first marched against private police in March 2018, approached the mic with a big sigh, and answered as best he could.

“I care because I am black, I care because I am queer, I care because I understand the implications that a private police force would have on black and brown bodies and queer bodies,” Burnett said.

The student snapped their fingers, they hugged, they called out the university some more, and declared the movement not over quite yet — it seemed like they would just have to keep explaining it to the people in charge.