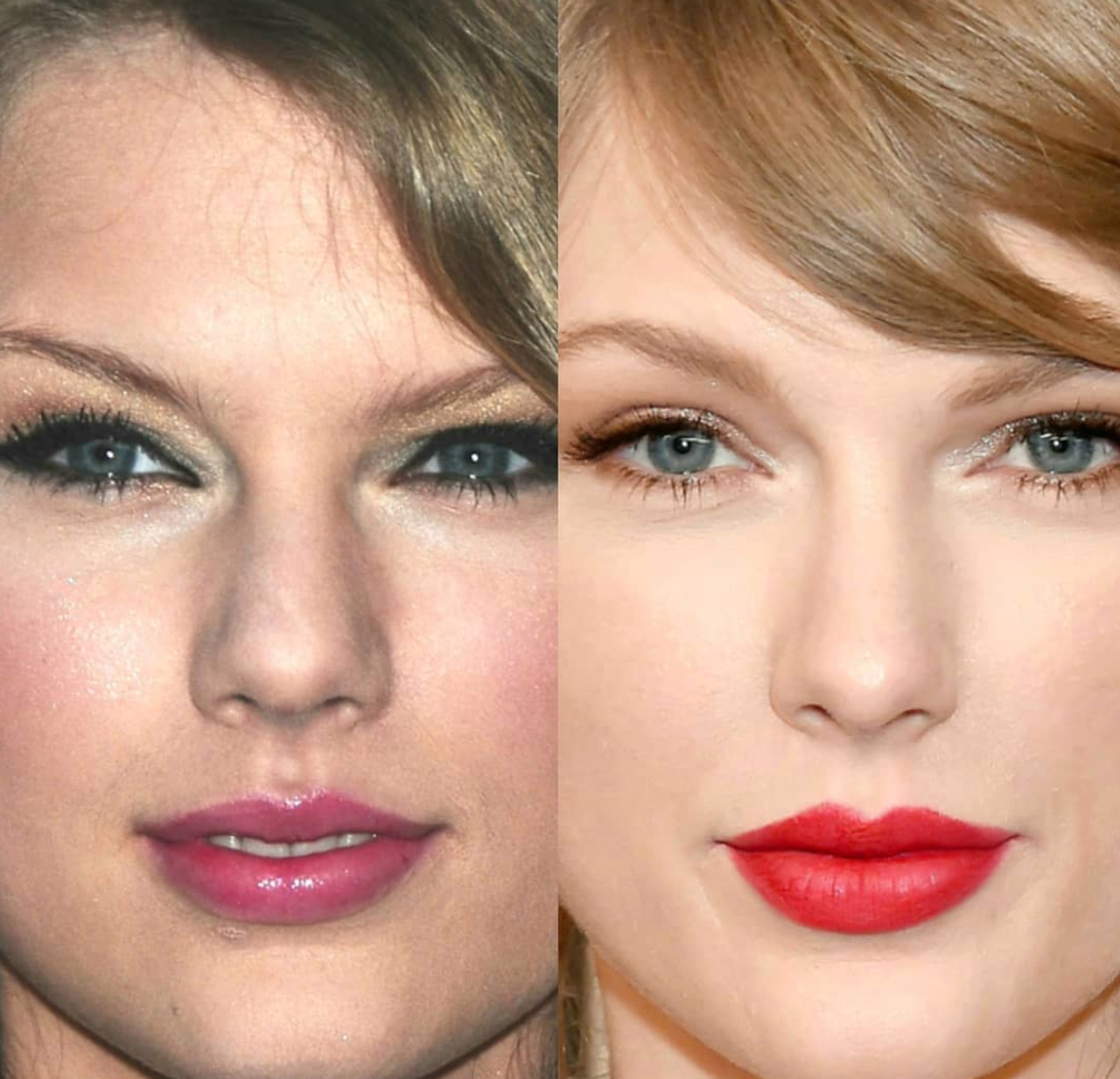

In the image below, on the left, Taylor Swift is wearing a sickly-sweet pink lip gloss, beneath which huddles a clumsily-concealed blemish, and tight-lined eyeliner with a smoked-out wing. There’s an excess of glitter on her deep-set brow and hooded lids, and cool-toned blush spreads across her slightly oily cheeks.

On the right is Taylor more recently. Her lips, cloaked in smooth red lipstick, are plumper. Her lids are still painted with the almost trademark glitter, but the thick eyeliner is gone. The area under her brows appears more spacious, like they’ve been lifted, and her eyelids are more defined. Her nose is thinner, and her hair has been transformed from a light mousy brown to a golden blonde.

This image comparison is from @celebbeforeafter. Many of the comparisons are startling: the Jenner sisters, for example, almost resemble entirely different people in their before and after pics. But in others, like with Taylor, or Beyonce, the differences are subtle; it isn’t necessarily clear if the changes are the product of better makeup artists or plastic surgery.

I have complicated feelings about @celebbeforeafter and other sites of its ilk, like @celebface, which Jezebel’s Hazel Cills brilliantly investigated in a 2018 essay. They aim to rip off the facade of celebrity, but in so doing can feel like they are adding an element of shame and ridicule to what these (mostly) women are well within their rights to do. But I also feel a sense of deep relief, because as a women in modern American society, I’m confronted every day, by media, advertisements, and social media, with ways I could be better, more beautiful, more like, say, Bella Hadid — if only I tried hard enough.

Women’s media has come to be a set of two very confusing poles. On the one hand, there is the validation/self-care set that preaches personal agency, selling products predicated on the belief that we need to better ourselves, telling us that we can and do control our destinies, whether that’s in our careers and love lives or, more relevantly here, our skin and bodies. Some even goes so far as to say we should embrace our flaws, that acne is cool, that anti-aging is out.

This bootstrapping perspective, implicitly endorsed in Into The Gloss “Top Shelf” interviews with the professionally beautiful or product rundowns on PopSugar, teaches us that if we just buy the right skincare products, go on the right diet, practice the right workout routine, we can get closer and closer to an elevated, but supposedly accessible, echelon of beauty.

But that messaging can start to feel inconsistent, or even paradoxical, when it’s built on celebrities who owe their appearances to, we suspect, far more than an expensive night cream. Enter the somewhat seedier underbelly of women’s media that has far less critical clout than glossy personal care or fashion websites, that we consume with almost equal hunger.

They’re on Instagram, like @celebface and @celebbeforeafter, which have 832k and 26.5k followers, respectively. They’re beauty blogs, like The Skincare Edit, which exhaustively combs through celebrity photos over the years and gets dermatologist opinions on the plastic surgery the celebrities have (apparently) gotten. And they’re websites dedicated entirely to the practice of dissecting celebrity cosmetic work, analyzing body part by body part as each has been “perfected.”

Before and after pictures, which depict what at least appears to be very obvious improvement, often in the form of plastic surgery, are a bold reminder that so much of the beauty we see depicted in the media isn’t “natural,” but is rather carefully crafted and artificial.

Celebface, which often showcases closeups of celebrities in which every pore, blemish, and wrinkle are laid bare, without the airbrushing that erases any flaws before a celebrity is presented to their fans, makes an even stronger, more comforting argument: that all the plastic surgery and money and effort a celebrity puts into their appearance will never fully propel them into the sublime, not really. That they, like us, are imperfect specimens. That the most supposedly beautiful people in the world require layers of makeup and Facetune before we, the ugly, pimpled public, are allowed access.

These Instagram accounts do what no women’s media brand today would allow itself, lest it be cast (rightly or wrongly) as body-shaming: they show their audiences how stacked the deck is when we compare ourselves to a gorgeous celebrity. This isn’t to say there’s no element of shame in some representations of this genre, like the tabloids you see at grocery store checkout counters. In those, which plaster images of celebrities in various states of disrepair or imperfection, the insinuation — sometimes, but not always, explicit — is that these stars could be doing better. They’re failing.

“We do know that viewing images, whether they’re doctored as things are nowadays or just images of quote unquote perfect women...the need to live up to that definitely has a negative psychological effect,” Tiffany Brown, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California Eating Disorder Center, told me. Viewing images of “perfect” women, she said, “induces a negative mood state, and causes people to internalize the messages the images are sending, that you need to look like this to be valued or successful.”

One 2010 study found that, among dermatology patients, body dysmorphic disorder — in which a patient has an impairing preoccupation with perceived flaws in their appearance — is “relatively common,” particularly but not exclusively among patients at the dermatologist’s for cosmetic reasons. Another study, from 2001, found that study subjects had poorer self body image after viewing images of thin models than after viewing images of average-sized or plus-sized models, or inanimate objects. And a 2011 paper in Cultural Sociology about celebrity and media impact on plastic surgery stated that “popular and media culture today are introducing a wholesale shift away from a focus on personalities to celebrity body-parts and their artificial enhancement” (emphasis in original).

As cultural obsession with celebrity body parts continues to rise, so too does our obsession with our own body parts that are “in need of improvement.” This has led to a steady uptick in plastic surgery, particularly in breast reductions, fat freezing, cellulite treatments, and lip implants.

“If you have a society that is constantly emphasizing that anyone can pull themselves up by their bootstraps and we can all be Horatio Alger,” said famed neurologist Robert Sapolsky in a recent interview with Ezra Klein, “and if you’re not, [if] you had the control [and failed], that’s an incredibly corrosive source of stress.” Though Sapolsky was specifically discussing poverty and stress in the interview (which is amazing, by the way, and worth listening to), it seems applicable here. Because we do live in a society that emphasizes to women how they can be more beautiful if we just try.

According to Brown, @celebface and other, similar accounts can function as a sort of cultural accountability project. “More things like @celebface or accounts or organizations or even people recognizing or calling out what isn’t real and what might be altered or what might be unrealistic, I think is helpful considering the messages we send in media,” she told me.

“Very high standards — or impossibly high in the case of perfection — just set you up for feeling ‘out of control’ or like a failure,” Katharine Phillips, a professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College who has done extensive research on body dysmorphic disorder, told me. “Excessively high standards can seriously damage your self esteem.” A study from 2017 elaborates on Phillips’ assertion; it found that “perfectionism” has risen among young people in recent decades, and that “young people perceive that others are more demanding of them, are more demanding of others, and are more demanding of themselves.”

Brown said she’s noticed a growing tendency for women to question the images they see in marketing materials, which has led to brands attempting to present themselves in more “authentic” ways. Aerie, American Eagle’s lingerie and loungewear brand, famously stopped photo retouching in 2014, a move which has correlated with record revenue growth for the company. Other brands, like Modcloth and ASOS, have also pledged to avoid retouching photos.

But these changes are little more than savvy marketing moves, a patch on media’s otherwise relentless artificiality. Celebrities still feel compelled to doctor their noses and shave their chins, and the world still pressures them to not be forthright about it. Teens still don’t feel their portraits are “social media-ready” until they’ve blurred their freckles and trimmed their jawlines. And I, a person who is paid to think critically about these issues, still fret over the deepening worry line between my brows.

So every night I rub retinol on my forehead, around my eyes, and on my smile lines, because retinol is supposed to make those fine lines become less noticeable. I also use a salicylic acid toner several times a week, to dislodge the gunk in my pores; an alpha hydroxy acid serum whenever I remember, to smooth out any uneven texture; a hyaluronic acid serum to “plump” the surface of my skin (which, to be clear, topical hyaluronic acid can’t actually do); a niacinamide micellar water once daily, to cleanse and reduce pore appearance; a brightening toner, because I’m reaching 30 and my skin needs to be “brightened”; a moisturizer, to seal all that stuff in and all the bad stuff (pollution, dirt) out; and, of course, sunscreen.

Celebface and its brethren are not, by a long shot, the sole answer to the fake news and hypocrisy woven into beauty and entertainment media and advertising. But they’re a blip in every celebrity’s perfection radar, a little mirror that holds up our societal expectations and shows us the acne-scarred underbelly.

It would be possible to interpret the raison d’etre for something like Celebface as catty, meant to tear people down. But the photos on Celebface are less about the people in them and more about the world they, and we, live in, and what we are and are not “allowed” to talk about. Celebrities are trying, just like we are. And, yes, they’re more successful at it. They have more money and more resources than most of us could ever dream of. But beauty is effortful, these accounts say. And it isn’t always perfect.