Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

When I was 16, I was committed to reading contemporary fiction for the sole reason that I wanted to discard myself in the ruins of recent memory, and somehow come out of it donning the personality of a more interesting person. Forgoing and decolonizing the canon was hardly my most pressing concern — I read not for craft, but for the simple enjoyment of being anywhere but my unwieldy brown flesh inside the suffocatingly small Hong Kong public housing complex where I lived. That summer was filled with names like Jonathan Safran Foer, Nicole Krauss, Tea Obreht, Haruki Murakami, a far cry from the long-dead Bröntes of reading lists past. And then I found, nestled in the new fiction section of the local library, a hardback copy of Zadie Smith’s NW. I had never heard of her prior to that point, but as a sucker for excellent cover design, I went and borrowed the book.

NW loosely follows the lives of Leah Hanwell and Natalie (formally known as Keisha) Blake, two best friends who have grown in and around the Caldwell public housing complexes in northwest London (hence NW, the postcode). Leah is white; Natalie is black. Leah finds herself working at a non-profit after a raucous adolescence and a degree in philosophy; Natalie becomes a lawyer and embraces ascendent middle-class life complete with two children, a nice house, and a rich banker husband who failed his bar exam. Leah is easy-going; Natalie has a very unstable sense of self. Both come from impoverished families; both are not entirely happy with the lives they are leading. I saw Natalie’s trajectory as something similar to mine, an amorphously-shaped bookish teenager who was for all intents and purposes going to study law for money, and for people to take me seriously.

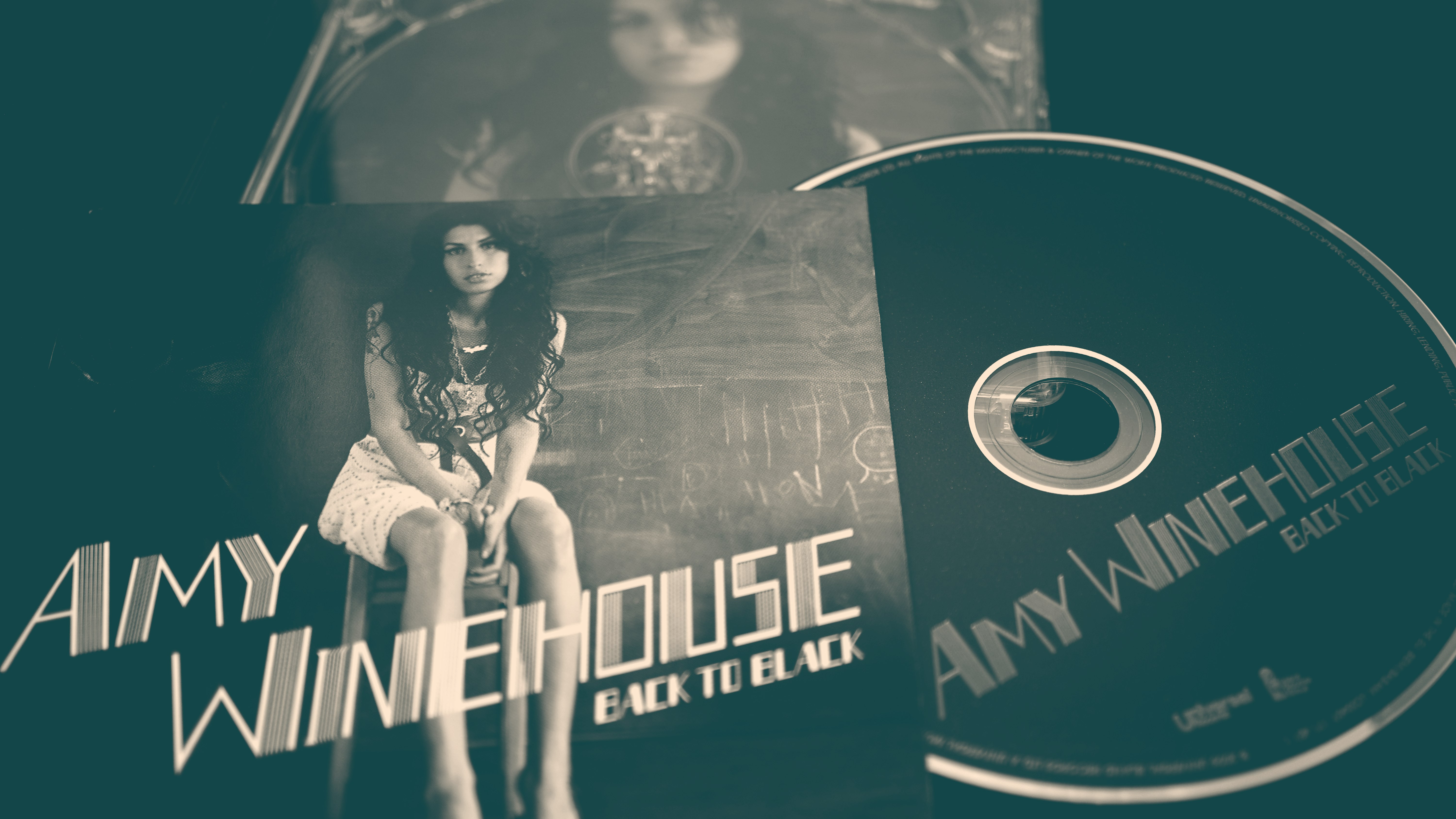

I distinctly remember the joy of reading NW for the first time as that sixteen-year-old, revelling in the snippy sentences, the references to hip-hop and pop music woven into the novel’s structure. In place of literary allusion was A Tribe Called Quest; in Smith’s depiction, Michael Jackson blasted from car windows and characters quoted Nas. Some readers would consider this part of Smith’s setting up window dressing for her realism, a mention of Jay-Z here and a mention of a stereo there just to hit home that we were still in the early 2000s without mentioning the fact. At the time, I thought something even simpler, and more vital: that the sundries of my life, such as sulking to an album, could be elevated and made transcendent by art.

“My thing is that good novels are really fucking rare. They’re just really rare. So I totally agree with everyone who says it feels like the novel is dead — because it always feels like that.”

It will never not surprise me that Zadie Smith has her own website, even if it was obviously set up by her publisher. To me, it’s a bit like plastering posters around town advertising a Beyoncé album. Smith’s reputation is the best promotion for her writing; any profile or review of her work has to mention the fact that the first 80 pages of her debut novel, White Teeth, was sold to a publisher for a lucrative advance when she was 21, meaning she wrote most if not all of her book while still at Cambridge. She was profiled in The New York Times by none other than Jeffrey Eugenides. Almost every single piece about her mentions in some way her beauty and her wit and her charm in person; a profile of her in 2000 compared her to Lauryn Hill.

What stood out as I went rummaging through the internet for more shards of Zadie wasn’t any of that. I was more taken with her love of hip-hop, her attendance at Cambridge despite having attended state schools and having lived in working-class Willesden for all her life. To me it seemed a regular life led by hustle and talent — a little of Natalie Blake, a little bit of luck. I still have one interview from these days saved to my Chrome bookmarks. For the rest of high school I’d go back to re-read it, as if it offered some kind of blueprint for becoming a writer like her, and I’d consistently return to her thoughts about the novel:

My thing is that good novels are really fucking rare. They’re just really rare. So I totally agree with everyone who says it feels like the novel is dead—because it always feels like that. If I made you read through all the novels that were published in 1912 or 1880, you’d be like, what an incredible sea of crap. And then you’d find a Henry James, or Ulysses. But I think there’s also a lot to gain from novels that are just quite good. There are lots of novels which are just quite good that have really made no impact on my life. I don’t mind those novels, I’ve got nothing against them. Long may they continue. (...) When I’m disappointed by a novel, why am I disappointed? And it’s really something so simple. For it to be a worthwhile novel, there has to be a reason for it to be in written language. In 1820, that was not one of the demands because there was no other option... But now... I could hear a song. I could watch a film. I could be on the Internet. You have to give me a reason why you have written this down.

Aside from the sick burns, across these interviews I found the shape of someone open about her desire to please to be liked, accompanied by some relatable self-loathing. But she was also unabashed about her cerebrality, describing herself as “an academic, a comedy-nerd, a theory-dork, a hip-hop-head” with an excess of affinities (she is allegedly also a Game of Thrones fan). I can no longer find efficacy in the notion of having a literary heroine, but for the longest time, as I oscillated between theory and writing throughout college, it was a comfort to read a critic who was as perceptive as she was modest on topics ranging from mixtapes to Roland Barthes, and who also happened to be one of the best writers of her generation.

As Smith notes, every few years or so, there’s a lot of hand-wringing over both sides of the Atlantic about the imminent death of the novel. Today, the debate over whether the novel is just a bourgeois form incapable of mapping the totality of our worlds has since given way to the heralding of pop-culture representation, a demand for more people of color, more women and non-binary people, some of them even queer, making an appearance in story-telling and bringing along their trauma. What we want, it is said, is the proliferation of narratives about people traditionally not made the focal point of bourgeois novels, even if you slot them into the same old white-upper-middle-class bildungsromans. The novel need not be a means of divining the future for clever literary critics. Literature is better off as literary fiction with a small L, where apparently authentic stories reign.

So what of Smith, who insists on the form, who “get[s] hung up on generalized theories of the novel,” who insists on writing about flawed black characters, who, for all her nebulous former-working-but-currently-upper-middle-class anxieties, is an astute writer of class? NW remains her best novel not just because it is an ultimately compassionate rendering of the brutality of growing-up in a world devastated by capitalist imperatives, but because this telling illuminates the possibilities of the novel form itself. It’s not just that the lives of Natalie and Leah are worth writing about; it’s that the novel and its conventions expand to accommodate the downtrodden, the just-getting-by, the people willing themselves to upward mobility that Natalie calls “miracle[s] of self-invention.” That hip-hop is included in the novel is not a novelty, but an act of real, formal import.

All of this was an expansion of what was permissible for me to imagine in fiction, which more often than not translates into what is permissible to imagine for ourselves in real life. We only ever call this a paradigm shift years after the fact, but what is felt as a slight re-adjustment to our lenses in the present ends up to have revealed the entrance to a whole new expanse of thought. It seems all so obvious now, but it was by reading NW and Zadie Smith that I began to realize that the minutiae of existence (including pop cultural artefacts) circumscribes meaning and structure, that class, like plots and sentences, are a structuring force in people’s lives.

Smith says she’s not a political person by nature, and that she doesn’t “have political intelligence,” but the problem of self-making under our ossified socio-economic circumstances is at the core of all her work. NW begins with Leah attempting to write down the words “I am the sole author of the dictionary that defines me,” and yet by the end of the book, both she and Natalie have conceded that their lives are delimited by a matrix of economics and circumstance. In her view, you can only “feel” free, which is also the title of her most recent book of essays. That feeling of freedom is what literature can give to the alienated and the displaced. It’s a gift, but not solace.

Speaking at the Inaugural Philip Roth Lecture in the Newark Public Library in 2016, Smith suggested that fiction offers an “ambivalent space in which impossible identities are made possible, both for authors and their characters.” It isn’t a space for aspiration necessarily, nor is it a place for the relatively narcissistic reader to find slivers of herself in the moving shadows and sentences of the novel. Fiction is unfalsifiable sentences arranged in a row pretending to simulate reality. You want reality? Go outside. Smith continued: “Great novels free us into an understanding that the tension between true/not true might in fact be livable, might not have to be judged and immediately neutralized in the court of public opinion or in the oppressive conservatism of our social lives.”

The fledgling critic in me is dismayed by the notion, but that sixteen-year-old reader felt freedom in reading NW, a sort of transcendence made manifest within my being. It wasn’t that I could identify with either Leah or Natalie, or even that the backdrop of Caldwell reminded me of my own housing estate. It was the first stirrings of ambition.