When I was a pretentious college student many years ago I really wanted to be an anthropologist. I loved to learn about other cultures, and the prospect of immersing myself in them to find out about their ways was much more appealing than my boring life. Ethnographies were amazing! I read every Ted Conover book. Wow, so much world out there, wouldn’t any 18-year-old want to dive in? Ride the rails? Me? Yes! In order to jumpstart my anthropology career I decided that I would undertake a collegiate project: Instead of studying abroad, I would transfer to a school that was the opposite of the one I was going to and write a report on comparative American colleges. My “study inbroad” would reveal deep truths about our country’s higher education system.

After three weeks at the University of Texas I realized I was a total asshole and an idiot. I was not prepared for this assignment. Texas was really hot. I knew no one. Many people had guns. And most importantly, no one cared why I was there or what I had to say and they were not going to let me join a sorority so I could write about it. I packed away my assiduous notes on the strange phenomenon known as rush week and, before long, began working on the college paper and saw that journalism was a low-paying, mainstream form of ethnography that also wasn’t as ethically dubious or critically high-minded.

Journalism still sucks and has many problems, but at least it’s a more universal and less omnipotent form of conveying truth about what is perceived as exotic or foreign, unfettered by the condescending Western ideals of ethnography (“Look at This Crazy Undiscovered Culture that is Only Really Crazy Relative to Western Culture but I Just Discovered It So It’s New to Me, Aren’t I Amazing and Brave for Deigning to Enter It!,” by Some White Man). Regardless, ethnography-as-journalism and its perverted cousin, new journalism (which, in our era, masquerades as stunt journalism), endure even though both are basically impossible to pull off in a manner that isn’t laden with moral traps. I mostly blame Gay Talese for this, and also for everything else.

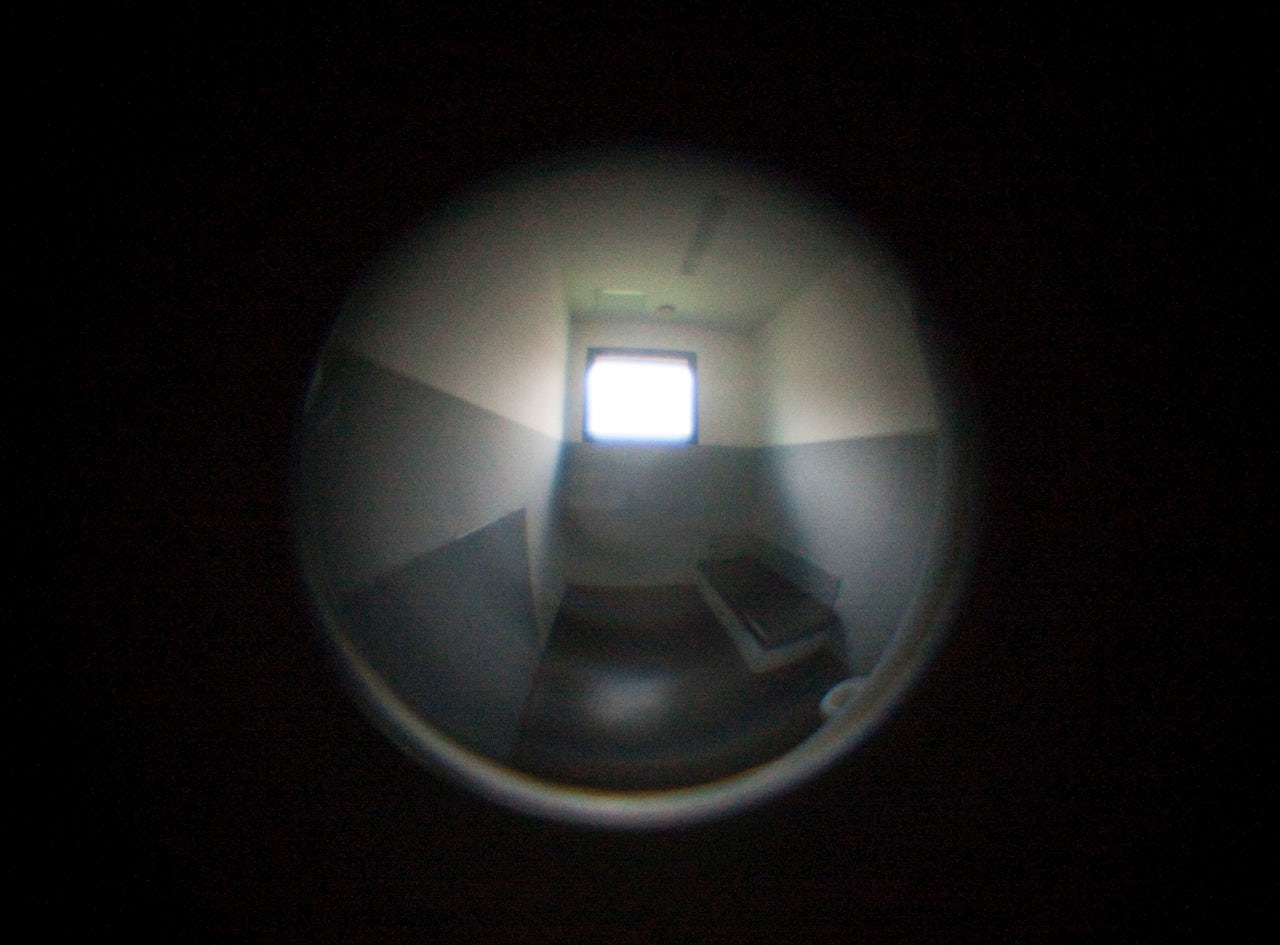

The latest example of troubling vector journalism is by Vice. For the next 30 days, Vice reporter James Burns will be voluntarily held in solitary confinement in order to “shine a light on the darkest corner of America's criminal justice system.” His experience will be livestreamed, so any voyeur can observe him pacing his cell, sleeping, or using the toilet. Vice and I agree that our prison system is fucked up and solitary confinement is a fucked-up practice. But the act of sending a free, relatively fortunate citizen (fortunate in that he is free relative to a prison inmate, I have no idea of Burns’ socioeconomic status) to endure something that is experienced every day by thousands who do not have the same rights as he does is inherently fraught. The proof of this is spelled out explicitly by Vice: Burns “will be able to ask for and receive release at any given time, Vice staffers will be monitoring him via video 24/7, and various emergency provisions are in place should he have medical problems.” Burns is not a prisoner. He can leave prison at any time. I assume he is getting paid for this stunt, as it is “work.” Although his experience might tell us how boring it is to be alone in a small space for an extended period of time, he is a participant by his own free will — not the harsh mandate of the law — which makes his time in solitary crucially different from the average resident, and also unreal.

Burns writes that this is not his first time held alone by authorities. The introduction to his stunt clarifies that he experienced a form of confinement as a kid: “He was left in a ‘quiet room,’ which is not the same thing as solitary in prison, but is nonetheless a traumatic experience for a child.” (A Vice representative clarified in an email after this piece was published that Burns spent time in solitary confinement as an adult too.) This experience might have been illuminating for a better piece of journalism; Burns could have also used journalistic skills, like talking to people who don’t have the option to leave solitary confinement, to illustrate the rancidness of it. But volunteering to suffer on a Vice livestream is not reporting, nor should it be considered in that way, and forsaking your comfort to “raise awareness” is not noble. It is more or less the journalistic equivalent of going on Survivor. It is the essence of reality television: brash, lacking nuance, ultimately fake, and monetized for consumption.

A lot of journalism is really gross. Most of it is a devil’s deal between reporter and subject — Janet Malcolm said something like that once, I think. Even the idea of foreign correspondence is rife with ethical snags — a practice long carried out by white men, dependent on the low-paid work of locals, to explain things to other white men. That perspective still dominates. How do you do journalism without being a complete fucking monster, preying on the weak for one’s “craft” or in the name of some slippery truth? What is even true, anyway? How can anyone ever “know” things?

To build on Malcolm, I would say that any time a journalist enters himself into a story, the story loses its chance to capture an essential truth. The modern story of solitary confinement is simply not James Burns’ to tell; it belongs to the some 25,000 people actually in solitary confinement. Using oneself as the vector, even in this extreme manner, is the easy way to tell a story, and the urge to do it is an immature one, as I learned early on. Building a relationship, forming trust, and communicating with an inmate and those around him would be a much more difficult task for Burns, because there are stakes involved that extend past the journalist’s own well-being. An oppressive or extraordinary situation simply cannot be mocked up for reportage purposes, the experience would therefore be intrinsically inauthentic and thus untrue. (For what it’s worth, this is a better prison story by Vice.)

Experience must be genuinely endured to be known. The truth cannot be created, or recreated. This is why journalism is hard and people are paid to do it. But the act of telling someone else��s story truthfully and effectively in a manner both faithful to them and translatable to the passive public should be extremely difficult. It is a higher art, and the highest service.

Get Leah Letter in your inbox.