Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

By 1988, Tom Hayden had come a long way from his radical youth, but his burgeoning political career would not go as far as he had planned. A chorus of right-wing voices had started raising concerns about his ambitions, which appeared trained on the White House. That scenario, however unfeasible, could not be brushed off. “A man with an idea is only dangerous if he owns a newspaper or a television station or has a wife who makes $3 million a year,” said Gil Ferguson, a Republican member of the California State Assembly. Though Hayden himself was only a small-time state assemblyman, he had leftist ideas and a dangerous advantage — not a newspaper, or a television station, but his wife.

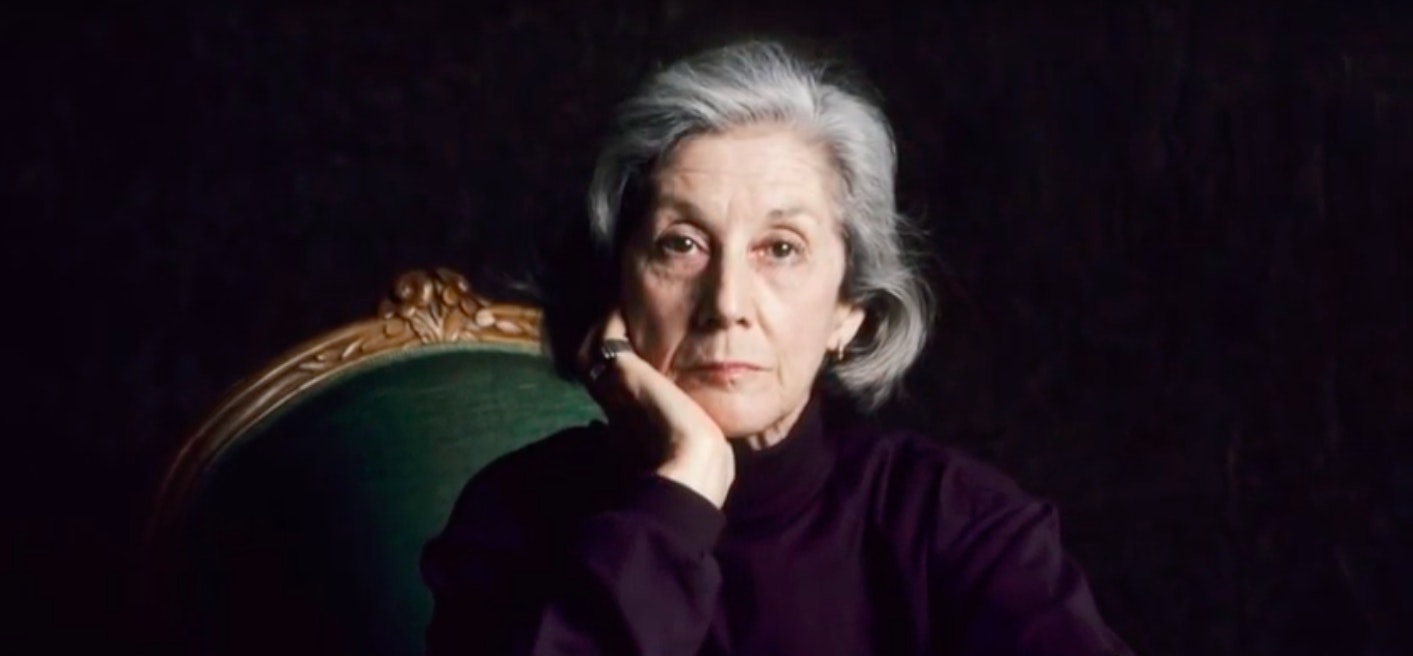

Jane Fonda, who’d married Hayden in 1973, was someone the right could not permit to gain any real political power — at least not if there were any truth to rumors at the time that painted her as an artfully ambitious narcissist intent on becoming First Lady. The scenario wasn’t an impossibility: However left of center her politics may have been, Fonda’s multi-million dollar fitness empire and resilient popularity meant her ceiling was very, very high. Her two Academy Awards and millions of workout videos had, by 1988, eclipsed the controversy over her 1972 trip to the North Vietnamese capital of Hanoi. Sixteen years later, even some veterans had even softened their stance.

But 1988 was also the year when a small group of veterans would protest Fonda filming her next movie in a Connecticut town, halting her forward march. The myth of Hanoi Jane resurfaced with fury, adding to marital troubles between Fonda and Hayden. Speaking with Barbara Walters for a June 1988 episode of 20/20, Fonda publicly apologized for some of her past political activity. It didn’t matter; shortly thereafter, things unbundled. The “Mork and Mindy of the New Left” split, and Fonda soon married billionaire Ted Turner. For the first time since 1960, she was out of the public eye.

Three decades later, Hayden and Ferguson are dead, Turner and Fonda are divorced, and “Hanoi Jane” is living her best life in the most earnest sense of the phrase, flourishing in a fifth act that transcends mere reinvention. Grace & Frankie reaches a broad range of ages, inspiring the young with role models of geriatric coolness. Book Club has been praised for portraying the pursuit of happiness well into one’s golden years. And in this moment when young people have lost any illusion that America is a place where all lives matter or where anything good actually trickles down, Fonda and her films from the 1970s have renewed currency. She registers as so relevant for this moment because it so uncannily resembles the one that made her iconic.

Her critics have been waiting for half a century to catch Jane Fonda in a lie; they have all failed.

I first put a face to Fonda’s name in 2005. She had just emerged from retirement and released her memoir, My Life So Far. For her first film in more than 15 years, she played the villainous Viola Fields opposite a post-Gigli Jennifer Lopez in Monster in Law. Though I knew little of her backstory, I was nonetheless fascinated: Fonda had the fuming mien of a ruthlessly honest woman short on fuses to burn, much like my Capri-smoking grandmother. What my boomer parents, with whom I watched the film, had to say about Fonda intrigued me even more. From my father, I gleaned Fonda was a “goddamn subversive;” from my mother, I learned Fonda was “an actress who protested the Vietnam War.” Both of them seemed to have more to say, but opted for the thick silence of someone who would really rather not.

I didn’t understand until recently how much there was to say. Nor did I understand how prodigious and polarizing Fonda was that, at one point, the most powerful men in the world monitored her every move. I don’t entirely know if my surprise at this fact has more to do with an internalized sexism or with the prevalence of a Fonda narrative that recasts her political past as a hotheaded historical footnote. As scholar Katherine Kinney writes: “Hating Jane Fonda seems to transcend left and right. If you do not think she is a commie traitor, you probably think she is a dilettante; or if you think she once stood for something, you think she betrayed it all with her aerobics empire and media mogul husband.”

Her earliest efforts at activism in 1970 were infantilized and dismissed as the hippie dalliances of a rich naïf. (Fonda was 32.) In March of that year when Fonda appeared on Dick Cavett Live, her somewhat affected solemnity left the shrimpy host visibly nonplussed. Fonda’s decision to turn over a segment of her time on the show to her friend, Shoshone-Bannock activist Lanada Means, to expose federal violations of Native American treaties, likely did not help. In the next segment, Fonda asked very good questions of the Archbishop of Canterbury (another guest on the show, weirdly), making Cavett boil. By the end of the episode, he interrupts Fonda (yet again) to wonder aloud: “What’s become of lighthearted show folk?”

Neither Cavett nor the rest of the mostly male journalists who covered Fonda could understand that her politics were real, or that she did not move into a normal home in a working class Santa Monica neighborhood for publicity. They couldn’t understand that such a nice girl could be so humorless, or that an actress could so nimbly and intelligently argue her point. Neither, apparently, could the CIA. Fonda confirmed as much by reading the U.S. Congress House Committee report pertaining to her activities in Hanoi. In the material pertaining to her radio broadcasts, an “authority on Communist brainwashing techniques” testified to the House Committee that Fonda’s messages were “so concise and professional a job” that she “must have been working with the enemy.” Fonda had improvised most of them and scribbled notes for the rest, as she writes in her memoir.

Fonda’s incandescence has been deliberately dimmed, even in 2018, when the day seems to have arrived in which, as George McGovern predicted in 1988, “Jane Fonda will be fully atoned for anything that happened in connection with the war.” Still, conservative pundits and politicians continue to scrape some political capital from the stone marked “Commie. Traitor. Bitch.” In September, Fonda made a disastrous appearance on Megyn Kelly Today, in which she made a prickly dismissal of Kelly’s fumbled question about her past cosmetic procedures – a much memed interaction Fonda jabbed at in the press over the coming months. By January, Kelly had had enough and declared it was “time to address the poor-me routine.”

"Fonda was on to promote a film about aging,” Kelly said. “For years, she has spoken openly about her joy in giving a cultural face to older women." To Kelly, her question about Fonda’s plastic surgery was thus entirely in bounds; Fonda’s outrage simply gave the lie to her latest cause celebre. Kelly could have stopped here, but instead chose to invoke “Hanoi Jane,” citing it as evidence for Fonda’s own ostensibly questionable grasp of “what qualifies as offensive.”

For Kelly, much like for the Reaganite establishment in 1988, Fonda is an insincere dilettante, a roving appropriator, a scheming Nasty Woman. Whether betraying her country, gender, or age cohort, to Fonda’s detractors, she has always been a liar. She was too beautiful, too talented, too effective on the screen, on the page, or on the stage to possibly be anything other than a spotlight-blooming flower or a subversive weed. That her virtuosity is construed as the scheming of a “shrill” woman (as Fonda was often called) points clearly to what kinds of people are permitted to be dynamic, and to whom such dynamism is denied. Her critics have been waiting for half a century to catch Jane Fonda in a lie; they have all failed.

Fonda, by her own admission, is “not a dabbler.” Instead, she is that thing that women and femme-identifying people are not permitted to be: someone who was right all along. Her politics then are her politics now. The arrestingly eloquent woman who spoke truth to power, who eviscerated every man who interviewed her in the ‘70s, who spoke so lucidly of privilege, decolonization, and solidarity with the Black Panthers, indigenous people and the working class, is still here. It is the same Jane Fonda who plainly told Chris Hayes that #MeToo would not exist were the voices not those of mostly white, famous women. Fonda’s fifth act is not a reinvention: it is a reiteration of the things she has always said.