This year’s influenza outbreak has been the worst in a decade, and our bodies’ efforts to fight the disease off may be partially to blame. The immune system is supposed to battle the bugs that cause sickness, but sometimes those same defenses can spur pathogens to evolve to be stronger, according to new research published in Science. Different strains of a disease, that is, aren’t just clashing with your body’s defenses — they’re also skirmishing with each other to be the best at getting you sick.

“One of the biggest questions for anyone who studies infectious disease, or gets a disease, is why some pathogens make us feel so much more sick than others,” said Dana Hawley, a biology professor at Virginia Tech and one of the authors of the report. “Why does the flu make us lie in bed for days and days whereas the cold virus allows us to mostly go about our business?”

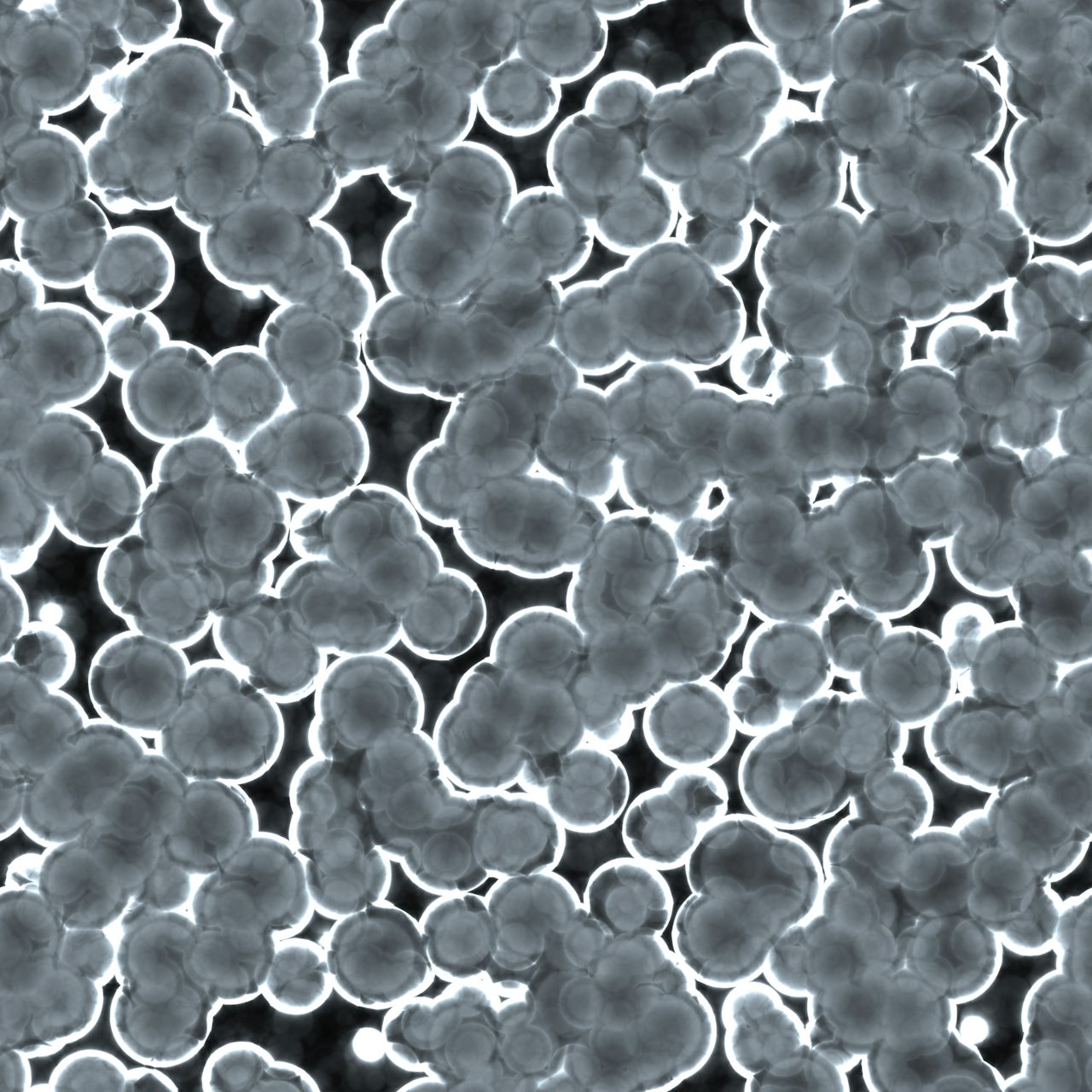

Hawley and her collaborators noticed that the symptoms of a bacteria called Mycoplasma gallisepticum, which infects the eyes of house finches, were becoming more severe with each generation. That’s surprising, at first blush, since sick birds are less likely to go out and infect others; you’d expect the bacteria to evolve to be less debilitating, not more.

To understand why that isn’t the case, Hawley and her collaborators watched recurring infections in 120 finches over the course of several years. They found that birds infected with a more virulent strain of the bacteria developed the strongest immunity to future infections — meaning that the nastiest strains of the disease mark their territory by excluding milder varieties from infecting the same bird later on.

The research fits into a growing understanding of the ways that organisms and the diseases that infect them interact in a generations-long co-evolutionary dance. It could lead, Hawley hopes, to understanding why some strains of common bugs like the flu are more debilitating than others.

The spread of disease through a population is a complex problem, and one with great benefits to health officials. Another paper published this week describes a new method that uses commuter data to predict flu outbreaks up to six weeks before they happen.