When Bob Marley died in 1981, he left a lot of things behind: a discography that changed reggae forever, a new standard for incorporating social agitation into music and celebrity, and a long list of heirs to transform his legacy into careers of their own. His children, including Ziggy, Damian, Ky-Mani, and Stephen have, to varying degrees of fame, established themselves as artists in their own right.

There’ve been various family business endeavors, too, led in part by Cedella and Rohan Marley: a Marley-branded audio company, a Marley-branded weed company, a Marley-branded coffee company, a Marley-branded beverage company, and a Marley-branded resort in the Bahamas. It makes sense; I’d probably do — or at least try to do — the same if my father were one of the most iconic, recognizable, beloved artists in history, and my family had paid $11 million to retain the rights to his name after his death. (“We borrowed the money, we paid it back, and it was ours for life," Cedella told Billboard in 2011. "That is part of the reason why we defend it so much. It was not something that was given to us.”)

But today, joining earbuds and single-origin espresso, there is also a Marley-branded pop star: Skip Marley, the 20-year-old son of Cedella, who is everywhere all of a sudden. He’s neither the first nor the only of Bob’s grandchildren to make inroads in the arts. There’s also his cousins Zuri (daughter of Ziggy, an artist who’s worked with Blood Orange); Daniel (son of Ziggy, a singer-songwriter); Jo (son of Stephen, a dancehall artist); and Selah (daughter of Rohan and Lauryn Hill, a model). But over the past few months, Skip has appeared in public as if chosen by the family, and he’s being marketed heavily as the second coming of Bob.

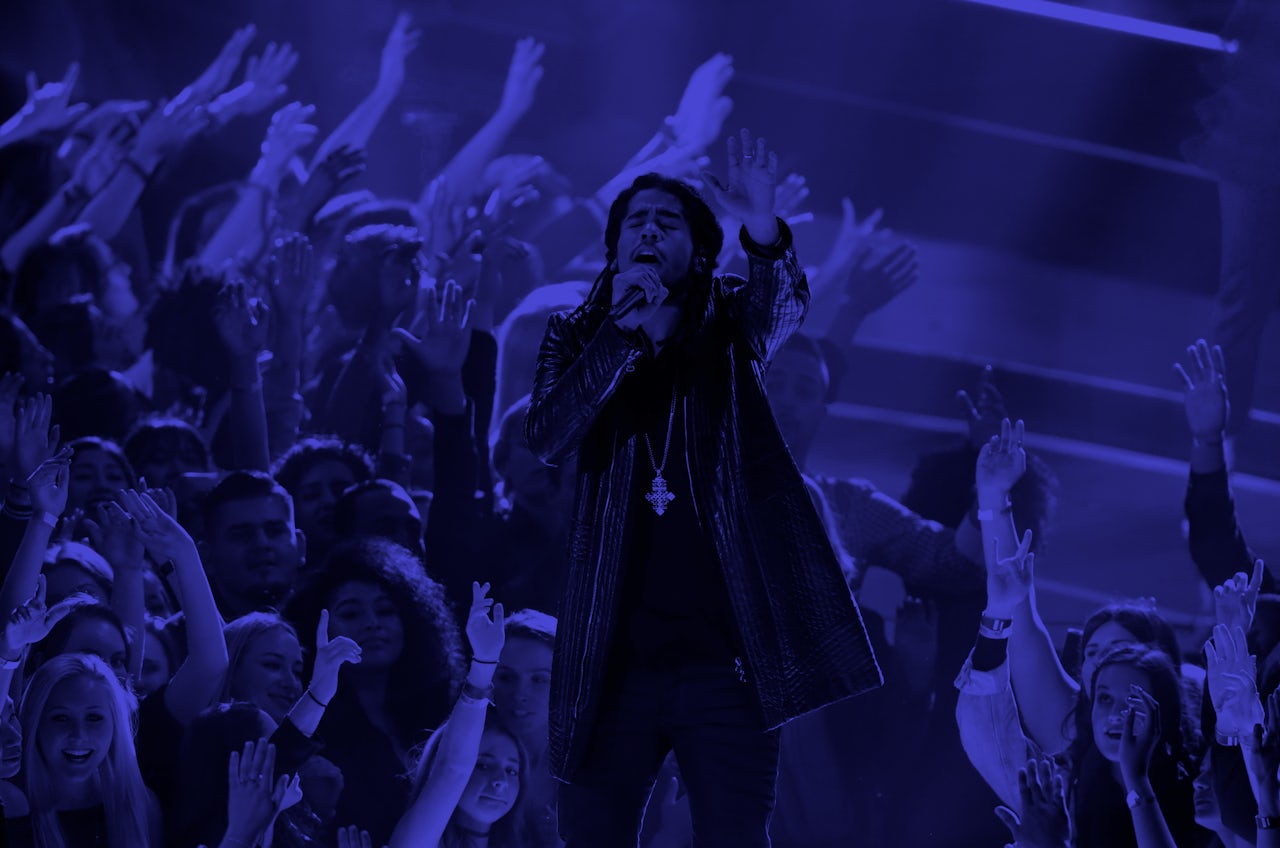

His major introduction to the world at large came earlier this year in the form of a guest verse on Katy Perry’s “Chained to the Rhythm,” the singer’s cloying attempt at a new woke identity. Skip’s verse is short — a few bars about “liars” in high places who “greed over people” and the impending “riot” that will bring them down. At the Grammys in February, he joined Perry onstage with a performance that had the pop charm and competence of a Jonas brother but none of the gut-punching emotional honesty and anti-establishment fervor that made his grandfather’s music the choice of liberation movements around the world.

The middlingly political lyrics of “Chained to the Rhythm” — “So comfortable, we’re living in a bubble, bubble/ So comfortable, we cannot see the trouble, trouble” — and her campaign for “purposeful pop” have earned Perry the descriptors “political” and “socially conscious.” And so too has it blessed Skip with the reputation of being, like his grandfather, in tune with social and political struggles, although it’s unclear what those struggles are, exactly. If you believe the story being peddled enthusiastically by his label and the music and entertainment press, Skip is a one-man revolution. The hashtag for his newest release, a nebulously anti-war track called “Calm Down,” is #WeAreTheMovement. An Undefeated profile from earlier this month references Bob Marley’s infamous anti-wealth stance and follows it up with the claim that “[y]ou can tell that Skip Marley ... has studied his grandfather in every way.”

“Lions,” the first single he released after signing with Island Records earlier this year, was described by Billboard as a “revolutionary anthem” and by Teen Vogue as being “a serious call to action.” Last month, Katy Perry called him “the voice of our revolution” (hmmm, whose revolution?). The song is fine, cleverly engineered to seem right at home on the radio while standing out as vaguely protest-y. The hook: “We are the lions, we are the chosen / We gonna shine out the dark / We are the movement / This generation /You better know who we are.” (“Lions” has not yet soundtracked any real-life resistance, but it did serve as the backdrop of Pepsi’s ill-fated, Kendall Jenner-starring protest-fiction advertisement.)

But here’s how Skip described his “revolutionary” intentions himself in a Genius annotation: “It didn’t stem from [the election], but it just happened to fall around that time. The song can be used in that way… You can say it, but it’s not really a political song. I don’t want it to be viewed as a political song because it’s not really that kind of song.” Or as he told Rolling Stone in March, "The world has gotten very tense … I felt like I needed to reassure people in the safety of love and community.” Great, thanks.

An “industry plant” is one of the worst things you can call an artist nowadays. Writing in Complex in 2015, Justin Charity defined the term as “a pithy derogative that we (haters) wield to imply that a rapper or singer is an upstart fraud, a record label puppet, a focus group-tested vessel of creativity so-called.” It’s a very specific accusation, one that’s agnostic of skill or talent, and focused instead on authenticity. You can play multiple instruments and write beautiful songs but if you’re an industry plant, you didn’t earn your success — someone purchased it for you. And there’s something especially gross about that. If anything should be a meritocracy, it’s art.

Skip Marley is not an industry plant in the traditional sense. He was not plucked out of a pop music incubator like X Factor, as One Direction were, or America’s Got Talent, as Kehlani was. But in his rise so far, we see two awful trends collide: that of the industry plant and that of social justice as a marketing tool. Music, yes, is a business, in which labels and other actors essentially place bets on artists and expect a return on their investments from fans, who are consumers. Consumers of pop have always bought glossy, neatly packaged stories and nowadays wokeness sells. Skip Marley is at the intersection of both, and his stock is rising.