In 2014, U2 partnered with Apple to make its 13th studio album come preloaded on every iPhone 6. The gimmick backfired, quickly. Customers complained about the unwanted presence of Bono on their phones, forcing Apple to share official instructions for deleting the album.

Despite its embarrassing end, the ploy represented the music industry’s burgeoning relationship with the tech world, and was a harbinger of an infuriating norm. By this point, many new albums from major artists had some digital component. But before long, it seemed inevitable that music releases had to be tech releases too.

A year before U2’s botched album giveaway, Jay Z had struck a similar, albeit considerably less aggressive, deal with Samsung. A $20 million agreement guaranteed a million Samsung Galaxy users early access to digital copies of his Magna Carta Holy Grail, delivered via an app called Magna Carta. It crashed almost immediately, and was accused of privacy violations. In the fall of 2015, Rihanna continued her mentor’s relationship with the mobile giant. The Samsung-sponsored ANTIdiaRY campaign promoted her album Anti by ushering fans through a months-long goose chase for a project that would eventually leak on Tidal.

These were neither the first nor last uses of tech in major music marketing schemes. In 2013, Lady Gaga released her album ARTPOP via an interactive app that also allowed her fans to do things like have their auras read. A couple of years later, in 2015, Usher launched a pop-up website to promote his single “Chains.” The site, hosted by Tidal, employed a technology requiring listeners to look directly into the eyes of victims of police violence in order to hear new music. Also in 2015, Pusha T premiered a song on his label’s website with a special tool that made users to hold down their mouse to listen. When the band Local Natives released a single last month, it launched a confounding web app that instructed users to close their eyes in order to hear the track. Aside from being unfathomably silly, the app hardly worked (at least not for me, a black person).

The music release via tech phenomenon has been around for years now, but there’s little evidence that it offers much beyond a frustrating listening experience. And yet it’s still being used.

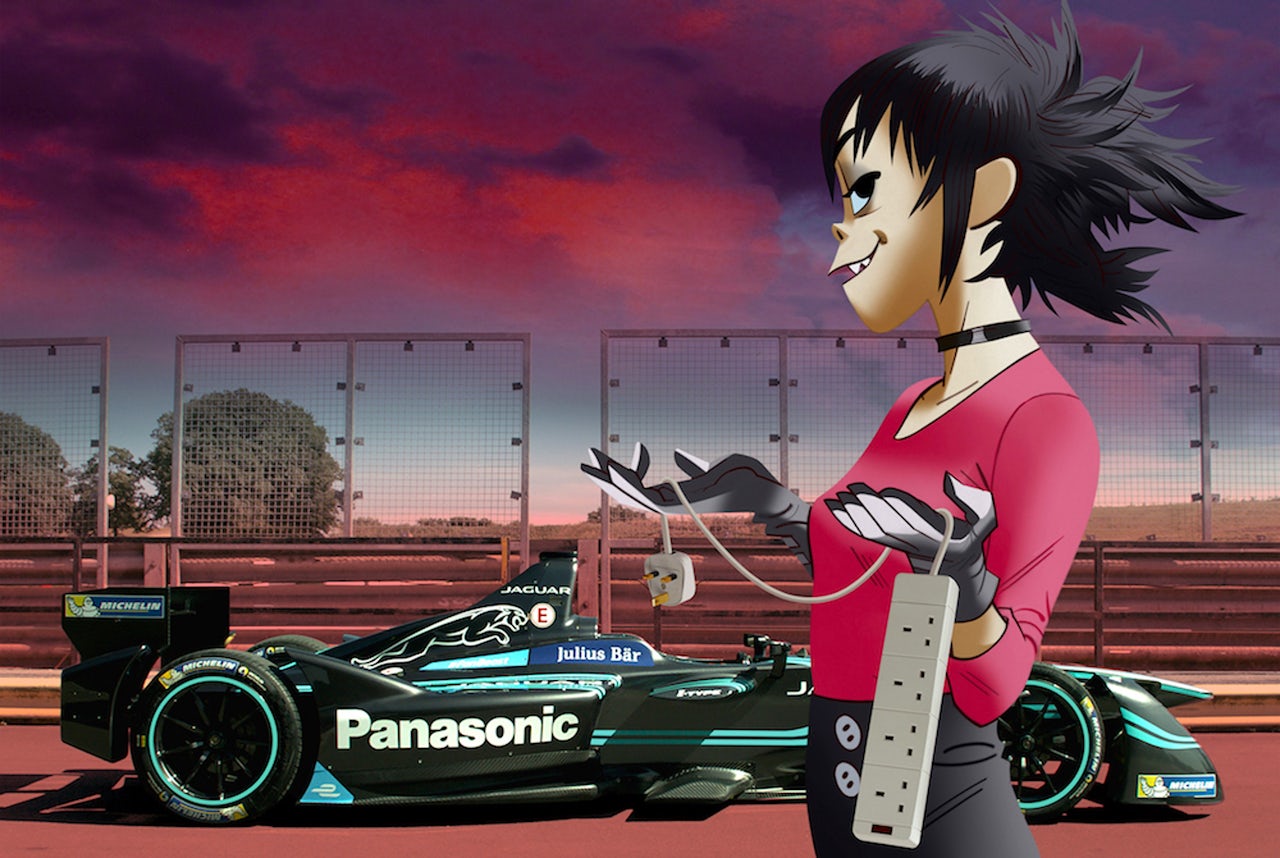

Take Humanz, the anticipated album from The Gorillaz that’s out later this week. The project was played in its entirety at a “secret�� show in London before being made available, briefly, on the animated band’s Humanz House Party app, which is sponsored by T-Mobile’s branded content site Electronic Beats. The Gorillaz app uses VR to bring an animated room, presumably the band’s lair, to life and encourages users to share their experiences through a hashtag.

You can turn your phone in any direction to navigate the space, and if you have a VR headset you can switch to full-on VR mode and look around. In one corner, there's a gramophone that can take you out of the app and into a Spotify playlist curated by the band’s fictional bassist Murdoc. Another token, a flickering analog TV, can take you to a random YouTube video of the character being “interviewed.” While the app changes daily, and sometimes premieres music, it offers little in terms of entertainment. Moving your phone around to navigate the room is interesting for the first few minutes, but a link to new music would have surely sufficed.

Branded apps are a barrier between fans and the music they want to hear.

Paradoxically, branded apps like this one are a barrier between fans and the music they want to hear. The clunkiness of such projects has become an unavoidable part of the album release process. But why would anyone put their fans through that?

There are likely a handful of motivations at play. Most obviously: money. A 2013 Nielsen study, presented to labels and music industry professionals at SXSW, described the opportunity that online streaming could create for artists, brands, and labels. Nielsen suggested that fans who spend money on digital music could stand to fork over a little more of their disposable income. “These fans, who spend between $20 billion and $26 billion on music each year, could spend an additional $450 million to $2.6 billion annually if they had the opportunity to snag behind-the-scenes access to the artists along with exclusive content,” the report reads.

Jay Z and Rihanna each collected a hefty sum from Samsung in exchange for releasing their albums exclusively to its customers, not too dissimilar from the way some artists give first listens of their projects to Apple Music nowadays. Elsewhere, musicians and celebrities such as Tyler, The Creator and Kim Kardashian have launched subscription-based apps with exclusive content. Taylor Swift released an app in partnership with AT&T that features “a video experience” designed to beam “unique videos, concert performances, behind-the-scenes footage, and more from the Taylor Swift archives” directly to her fans. In rare cases, an app can function as an extension of an artist’s creative vision. For example, Bjork’s trippy interactive music video project, released as a complement to her 2011 album Biophilia, was eventually featured in the MoMA.

Thanks to advances in streaming, the music industry as a whole is seeing a dramatic turnaround. Last year it saw its second straight year of growth, with $15.7b in revenue, according to a report by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI). Digital revenue, driven by streaming, accounts for 50 percent of that figure. After early chaos and signficant declines in revenue spurred by the internet and online piracy, the music industry appears to be recovering by generating income from technology.

With that digital success in mind, it makes sense that music release tech experiments have become a crutch for marketing schemes. It doesn’t matter that an app like The Gorrillaz’s is inane and ultimately pointless, just so long as it can potentially encourage you to spend more money on more stuff.