“My mother would be so proud that her cells saved lives,” Lawrence Lacks, the son of Henriette Lacks, recently told The Washington Post. The cells he refers to, known in scientific research as HeLa cells, are one of the most important scientific discoveries in modern medicine. These cells, which were taken from his mother at Johns Hopkins University in 1950 as she battled aggressive cervical cancer, are still in use today. They have been the foundation upon which vaccines, in vitro fertilization, and cancer treatments have been developed. Descendants of the original cells are still in use today. And now, Lawrence Lacks wants a new agreement for their continued use, as well as compensation for their already incalculable value.

The story of Henrietta Lacks’ life and that of her cells came to widespread public attention in 2011, on the publication of Rebecca Skloot’s book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Henrietta Lacks went to Johns Hopkins University for diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer in 1950. During her treatment, a researcher took a small amount of cells from Lacks without her knowledge or consent. According to The Washington Post, Johns Hopkins said in a recent statement that “when the cells were taken, there was no established practice for informing or obtaining consent from cell or tissue donors, nor were there any regulations on the use of cells in research.”

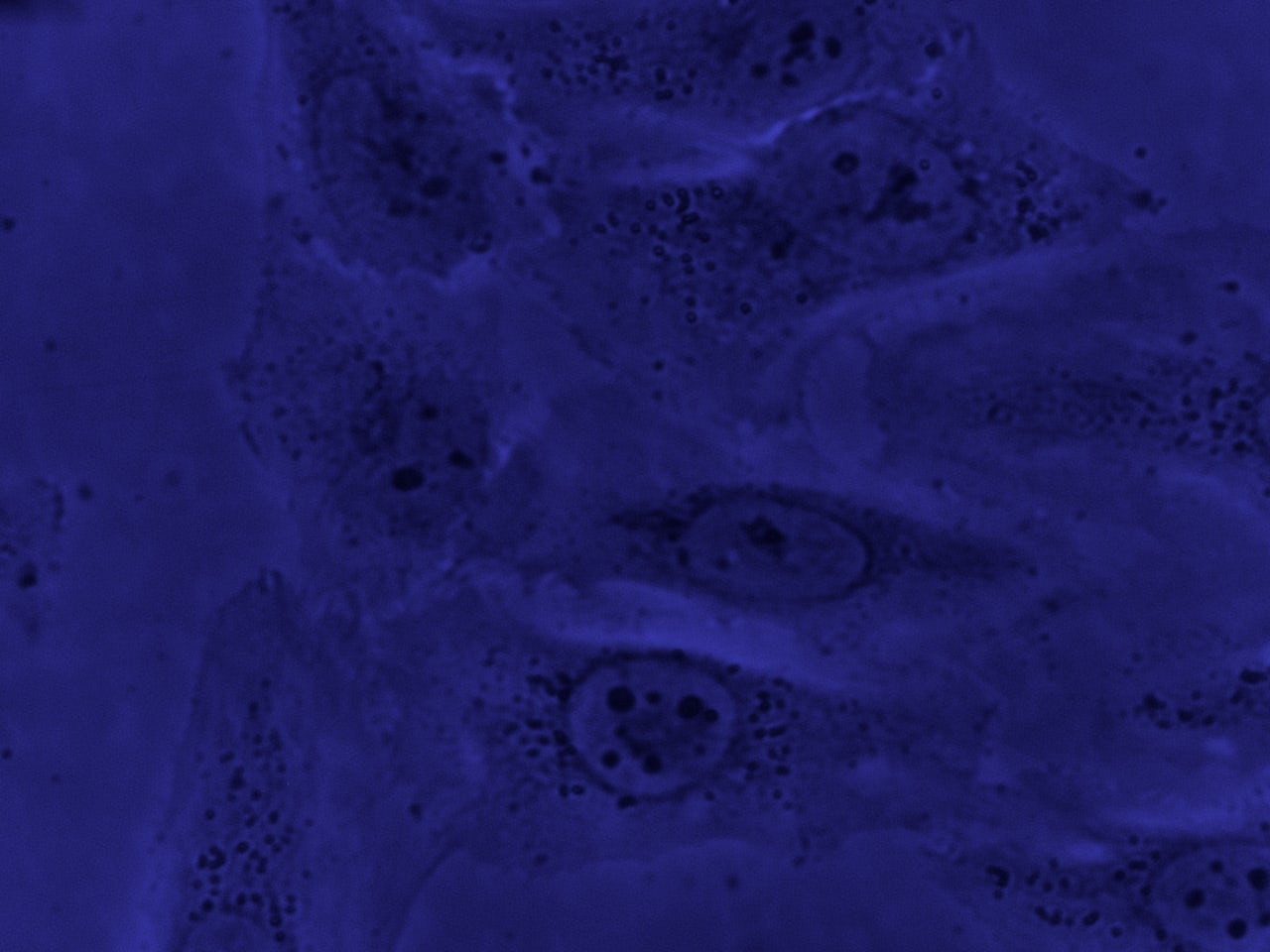

The cells, much to the surprise of the researchers, stayed alive in a lab. The type of cancer Lacks had was extremely aggressive, making the cells reproduce very quickly. They were the first immortal cells ever cultured in a lab, and they quickly became completely invaluable in scientific research and were shared for multiple research projects. The Lacks family didn’t find out about the existence of the HeLa cells until nearly 25 years after she died, when researchers tracked them down for further samples.

Henrietta Lacks’ daughter, Deborah, forms much of the core of Skloot’s book. Her sons have been, according to Skloot, “very angry” since they found out that their mother’s cells launched a multi-billion-dollar industry while the family — who has lived in poverty all this time — was never compensated. Johns Hopkins University maintains that it has never directly profited from the cells.

Lawrence Lacks has said that an agreement signed with the National Institute of Health in 2013 by some of Lacks’ family allowing continued, free use of the cells is not valid and that he will file a lawsuit in the coming weeks seeking compensation, though it’s unclear how much money he seeks. Lacks, who is 82, told The Washington Post that when he went to the NIH for explanation, they ”cut him off in the process.” “I really didn’t understand what was going on,” Lacks said. “Instead of explaining it to me, they went three generations under me.”