Considering New York magazine’s resident centrist Jonathan Chait spends much of his time obsessing over whether Oberlin students believe in free speech, his piece this week lamenting the remaking of the term “neoliberal” into a “term of abuse” is somewhat surprising. In a few thousand words, he refers to it as an epithet four times.

Chait writes that the term “neoliberal” is used to “separate its target — liberals — from the values they claim to espouse.” “By relabeling self-identified liberals as ‘neoliberals,’ their critics on the left accuse them of betraying the historic liberal cause,” the piece goes on, eventually arguing that the socialist “reveals a certain lack of confidence” by “trying to win with an epithet.”

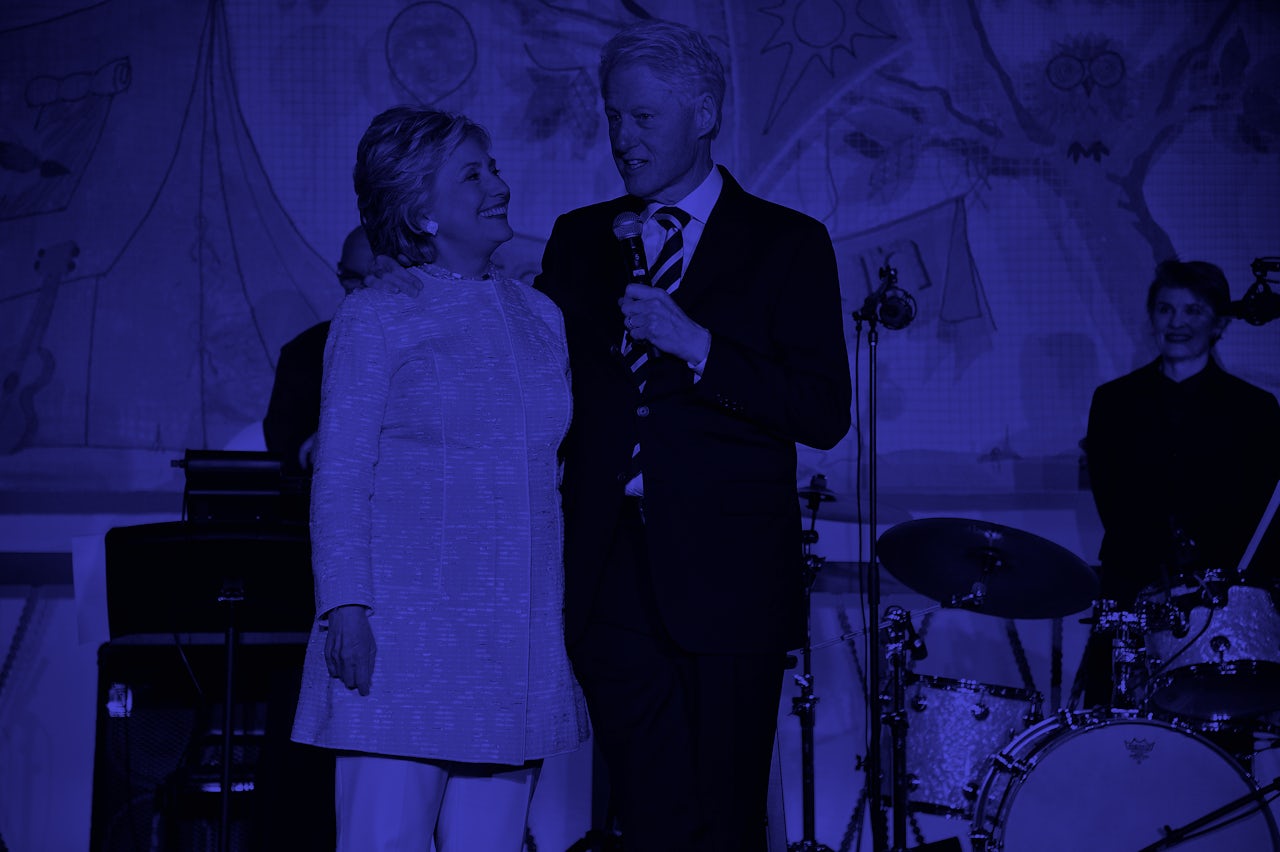

To understand Chait’s interpretation of the term, we must first define it. What the fuck is neoliberalism? Simply put, neoliberalism is an economic and political doctrine that characterizes deference to the free market and an inclination towards privatization, deregulation, and uninhibited free trade. Famous neoliberals (who don’t call themselves neoliberals) include the Clintons and basically any centrist or conservative politicians from the latter quarter of last century. Neoliberalism, in the Clintonian sense, is a paean to capitalism that masquerades as a defender of social democracy.

What the fuck is neoliberalism?

Although Chait dismisses the international definition of neoliberalism as inadequate for our current system dominated by two neoliberal parties, it’s helpful to trace the history of term. It dates back to the 19th century, when the French socialist economist Charles Gide wrote of a “hedonistic world”— he was a Protestant, so he thought this was an own — that valued “free competition” above all else. “That realm of pure political economy,” he wrote, “ever kept in view by the adepts of Neo-liberalism when they attack us and cry triumphantly, ‘You will never get further nor do better!’”

In 1951, neoliberalism was championed by the economist Milton Friedman, who wrote about it in a paper titled “Neo-Liberalism and its Prospects.” Friedman wrote of “a new faith” that could correct laissez-faire’s wrongs: “It must give high place to a severe limitation on the power of the state to interfere in the detailed activities of individuals,” he wrote. “At the same time, it must explicitly recognize that there are important positive functions that must be performed by the state.”

So why does Chait think “neoliberal” is a slur? Well, probably because it has become de rigeur to use the term derisively in describing people like him. In a recent piece for the Baffler, Chris Lehmann wrote of the “neoliberal wonk class’s painfully absent common touch,” and although he did not call out Chait by name, the neoliberal wonk was apparently angered enough to write a piece in response. “Obviously, the authentic way to demonstrate a common touch is to throw around the term neoliberal as frequently as possible,” Chait sneers.

Chait resents the term, but doesn’t prove why it’s an unfair characterization of what he believes. To argue his thesis that “neoliberal” is an epithet, Chait relies on an incomplete history of the Democratic Party over the past thirty years, one in which he claims that the neoliberalism of Charles Peters, the former editor of Washington Monthly who ushered into being the modern use of the phrase, “never took hold.” Chait writes: “The neoliberalism of the 1980s and 1990s has faded into memory, as its adherents failed to settle on a coherent set of principles other than a general posture of counterintuitive skepticism.”

Chait gives three conflicting views about what the Democrats’ trajectory on economic policy has been. First, he says that the Democratic Party has “moved somewhat to the left” since the New Deal. But later, he says that the “basic ideological cast” of the Democrats’ economic policy hasn’t changed. Finally, he admits that, while the party’s core economic ideology hasn’t changed, they’ve been forced into a “defensive posture” by congressional Republicans, the kind of thing that makes the Democrats consider gambling away Medicare and Social Security to reduce the national debt. (Chait’s view of Bill Clinton here is drastically different than what he thought 17 years ago, when he wrote in The New Republic that the “mainstream liberal model of the economy now resembles the pre-Reagan Republican model.”)

If Chait is right about one thing, it’s that the Democrats ‘have never been a left-wing, labor-dominated socialist party.’

As opposed to socialism or even the New-Deal welfare-state liberalism of FDR, the Democratic Party since the 1980s has leaned on policies like Medicare and Social Security. Chait notes that Clinton tried unsuccessfully to establish universal healthcare, but what he conveniently leaves out is that in 1994, when the Health Security Act (also known as Hillarycare, as the then-First Lady was instrumental in its formation) failed, the Democrats had a 79-seat majority in the House of Representatives and a three-seat majority in the Senate. Republicans didn’t kill Hillarycare; the inability of congressional Democrats to pass it did.

Likewise, when the Obama administration took up health care reform, the White House dismissed Medicare for All and, later, then-Sen. Joe Lieberman derailed the public option, as Chait argued for The New Republic in 2009. “To put this government-created insurance company on top of everything else is just asking for trouble for the taxpayers, for the premium payers and for the national debt,” Lieberman said at the time. “These exchanges that we’re talking about, I think, are going to drive competition.” Of course, Lieberman and the subservient devotion to “competition” by both parties exemplifies neoliberalism in its most primal form.

Lieberman's legacy of shit stubbornly lives on. There are the four Democrats who voted to kill the Obama administration’s stream protection rule, and the 13 Democrats including Sen. Cory Booker who voted against an amendment introduced by Sen. Bernie Sanders earlier this year that would have created a reserve fund allowing Americans to import cheaper drugs from Canada. There are the Democratic power brokers who oppose single-payer health care, despite the fact that their base vehemently supports it.

All of the hallmark facets of neoliberalism — competition, free markets, deregulation, unchecked inequality — also, of course, characterize the policies of the Republican Party. But despite the Democrats’ relative move to the left on social issues (so long as they don’t throw reproductive rights under the bus anytime soon) the party’s fundamental economic ideology is that too much government intervention in the economy, too much regulation, and too heavy of an expansion of the safety net are all bad things. If Chait is right about one thing, it’s that the Democrats “have never been a left-wing, labor-dominated socialist party.” And what’s more confusing is that all of these words — centrist, neoliberal, corporatist — all mean a similar thing and describe a particular type of politician. There’s a better, all-encompassing description of politicians from both parties: capitalist.

It seems that Chait and other neoliberals can’t make up their minds about whether being called a neoliberal is an insult or a badge of honor. In an op-ed last month for the Los Angeles Times, the columnist Jamie Kirchick compared the term to George Orwell’s definition of fascism, in that it had “no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable.’” Likewise, Chait argues throughout much of his piece that neoliberal policies are a good thing — he praises JFK at one point as a “cautious trimmer,” and cites FDR’s formation of the Export-Import Bank as analogous to Clinton-supported trade deals.

What Chait seems to be more frustrated about is the fact that for the first time in decades, neoliberalism is more than a term of endearment for the center — it is now widely seen as an umbrella term for the country’s ills. “It is strange, though, to apply a single term to opposing combatants in America’s increasingly bitter partisan struggle,” he laments, but that’s the point — both parties got us into our current predicament. It turns out there’s nothing more bipartisan than neoliberalism.