Aisha Flood swears she had a conversation with her brother, Maurice Harden, around 3 a.m. on June 5, 2013. She was recovering from a recent surgery and says she had an out-of-body experience.

“He was sitting right in the room with me and we were having a full conversation as if he was there,” Flood says. “About my health and things we were going to do, and he was telling me that everything was going to be okay, that I wouldn’t be in pain anymore, that I wouldn’t suffer. That he was always going to have my back.”

The next morning, twenty minutes after her husband and aunt left her house in a working-class neighborhood in Southeast Raleigh, North Carolina, Flood awoke to the sound of the doorbell. She opened the door to find a police officer. “Do you know Maurice?” he asked her. Thinking they meant her husband, who is also named Maurice, Flood told the officer he had just left. After a back and forth, the officer asked: “Are you sure you know who I’m talking about — Maurice Harden?”

She told them Harden was upstairs asleep. She yelled his name, but got no answer, which was odd. When the officer began describing what Harden looked like, “this weird feeling came across me,” she said.

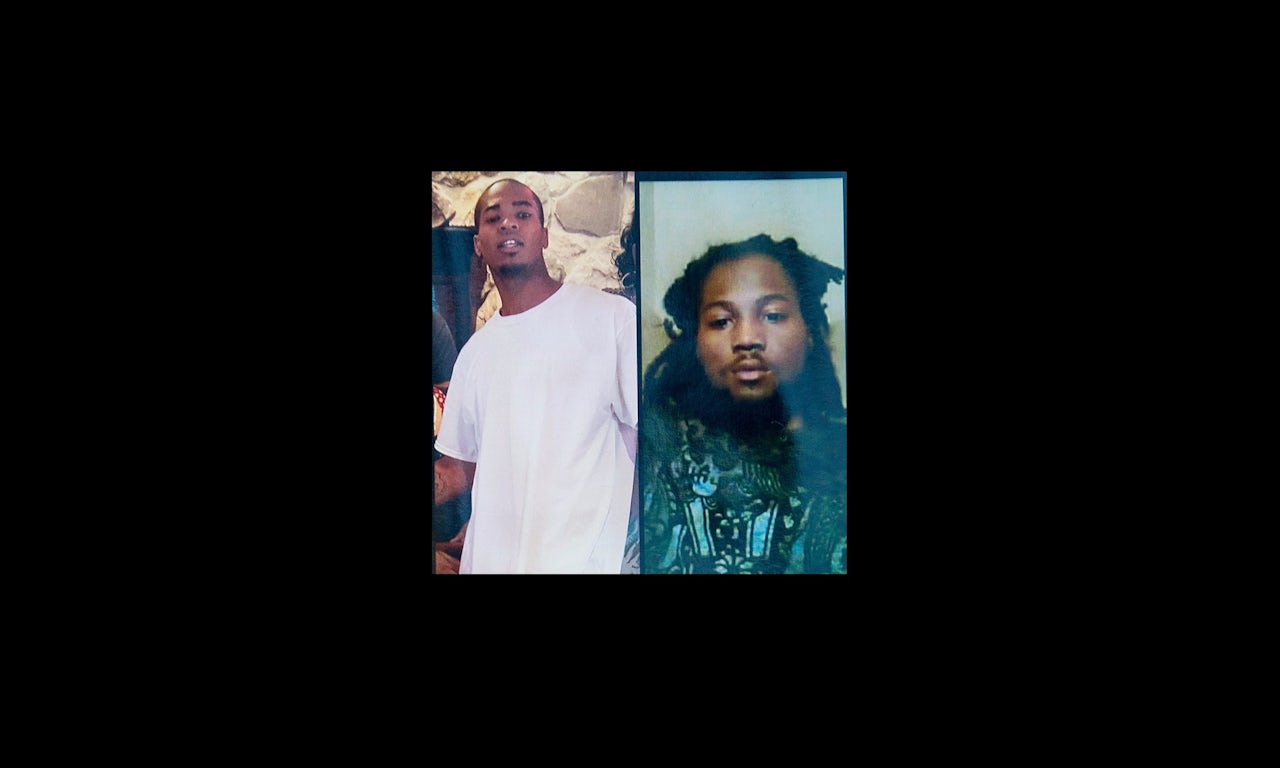

Harden and his friend, Trindell Thomas, 21, had been killed at approximately 3:06 that morning. A Raleigh police officer named Jonathan Crews, in pursuit of a speeding vehicle, clipped the scooter Harden was driving with Thomas on the back at 70 miles an hour, as they were turning into a friend’s driveway. They both died at the scene.

Harden’s death particularly affected his brother, Jaqwan Terry. They were close, and Terry told friends that he should have been there to “protect” his younger brother. “After [Maurice] passed, it really messed up his mind,” says Seneca Clark, the mother of Terry’s young daughter. “He talked about him pretty much every day.”

Three years later, Jaqwan would be dead, too, shot and killed by the Raleigh police.

There’s no complete national database of people who have died at the hands of police (although various news outlets have begun to compile shooting deaths in recent years), so it’s unclear if a situation like this — two brothers dying in incidents involving the same police department police under different circumstances — has ever happened before. It is certain, however, that it’s exceptionally rare, even though police shootings are not.

According to The Washington Post’s database of police shootings, North Carolina police killed 33 people in 2016, including Jaqwan Terry. In Charlotte, North Carolina, protests erupted last year after a disabled man named Keith Lamont Scott was shot and killed by officers in the neighborhood where he picked up one of his children from the bus stop. The officer who killed him was later cleared of wrongdoing by Mecklenburg County district attorney Andrew Murray, who said the officer “acted lawfully” when he shot and killed Scott. (The Charlotte Citizens Review Board recently ruled that there was “substantial evidence of error” in the police department’s finding that the shooting was justified.)

Raleigh, the state’s capital, has also had its share of controversy with regards to policing and the justice system. In February 2016, a man in southeast Raleigh named Akiel Denkins was shot and killed by a Raleigh police officer who said Denkins reached for his weapon. Witnesses initially stated that Denkins had been shot while his back was turned to the officer, but Wake County District Attorney Lorrin Freeman cleared the officer of all charges a month later.

Since April of 2008, nine people have been shot by the Raleigh police, three of them fatally. Eight of those people — including Terry and Denkins — were black. (Harden and Thomas were also black.)

Ten months after the crash that killed Harden and Thomas, two black men were stopped by a pair of Raleigh police officers. According to court documents, the policemen, Eric Vigeant and Dennis Riley — one of the officers involved in Maurice Harden’s death — didn’t find anything on the passenger in the car, but nevertheless drove both men to a vacant space in a strip mall where the passenger was strip searched and later “abandoned” after they didn’t find anything. At one point, the other officer reportedly told the passenger that, “‘after 9/11,’ the [police] could do whatever they wanted.”

The man filed a complaint with the Raleigh Police Department which, according to court documents, determined that the officers had violated policy relating to searches and seizures.

The case resulted in a lawsuit, which a public records request found was settled out of court for $117,000. Along with the $91,584 in legal costs to defend the officers, the city of Raleigh paid out well over $200,000 in the case. In an email, a Raleigh police spokesperson confirmed that both officers are still employed by the department and assigned to the same division as when the incident took place. City attorneys would later argue in a brief in the Harden case that Jonathan Crews, in both his individual and official capacity, was entitled to immunity.

When Maurice and Jaqwan were young, their family moved around a lot — North Carolina, Maryland, New York. Money was tight, and their mother, Cynthia, had multiple mental illnesses, family members say. Aisha, Jaqwan, Maurice, and their youngest sister Tay eventually went to live with their aunt, Patricia, in North Carolina. She gained full custody of the siblings, and the family moved to Winston-Salem. When they got older, they all eventually wound up in Raleigh.

Harden’s friends remember him as a generous, gentle presence. “A lot of times, I witnessed myself and other guys come at Maurice and try to fight him, and he wouldn’t even hit them back,” says Lawrence Quadel “Dell” Williams, Harden’s best friend. “He wasn’t violent at all.”

Harden’s family says that he was starting to figure out what he wanted to do with his life. Artistic and good with his hands, Harden loved to draw, and his family says he was taking architecture classes. He worked as a dishwasher, but also played the part of amateur mechanic, taking things apart and fixing them for fun. His sisters say, with a laugh, that he drew up a complex schematic for an underground bunker for his family in preparation for the apocalypse. At the time of his death, he was planning on enrolling in tattooing school.

He was also a devout Christian, and he and Dell Williams liked to study the Bible together. Once, when Aisha Flood was in the hospital for an illness, Harden told her: “I’m going to die before you because God has a calling on my life.”

Harden spent time in prison for nonviolent offenses, which the media latched onto after his death. In 2009, at the age of sixteen, he served six months for possession of a schedule II drug with intent to distribute, which included a concurrent one-month sentence for second-degree trespassing; three years later, he did two-and-a-half months for receiving a stolen vehicle. At the time of Harden’s death, he had a pending possession charge from March 2013; it was eventually dismissed.

His life story was not a unique one in a country where communities of color have been generationally devastated by mass incarceration. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, a Massachusetts-based think tank focused on mass incarceration, black people made up 22 percent of North Carolina’s population in 2011 but 61 percent of the state’s prison population.

After a recent law passed in New York, North Carolina became the only remaining state to treat 16- and 17-year-olds as adults by default, which denies them the chance to move their case back to the juvenile system via appeal. But amid mounting public pressure – including from the state’s chief justice of the Supreme Court, a Republican – the state legislature finally agreed this year to raise the juvenile age to 18 for misdemeanors and some nonviolent felonies.

“I know that young people, mine, yours, all across this state, will make bad choices, unfortunately,” former Republican lieutenant governor Jim Gardner said in a press conference in support of the move in May. “Simply because they make a simple mistake, it should not be with them for the rest of their life.”

On the night of June 4, 2013, Maurice Harden and Trindell Thomas were at Dell Williams’s house in Raleigh with Williams and a group of friends. It had gotten late, and Harden dozed off. At a certain point, Thomas woke up Harden and asked for a ride to a friend’s house, about 15 minutes away. Williams told them not to go, that it was too late, but after a while, he fell asleep. He estimates that the two men left the house on Harden’s scooter around 1 or 2 a.m.

As they drove down Skycrest Drive, a tree-lined suburban road in east Raleigh, the men stopped for gas. Thomas called the friend they were going to see and told her they would be there in five minutes.

Around 3:04 a.m., Raleigh police officer Dennis Riley began following the two men. In a deposition, Riley said that at least one of the men wasn’t wearing a helmet, and the scooter “seemed to be going faster than was legally allowed.” According to the crash reconstruction report, Riley said the scooter increased its speed from 35 miles per hour, the limit on that road, to 55 or 60 mph. Despite that, Riley said in his deposition that he didn’t witness any erratic driving, and didn’t attempt to pull the scooter over.

Another officer, Jonathan Crews, was parked in his cruiser on Skycrest when, according to a deposition Crews gave in August 2016 — multiple requests to interview Riley and Crews went unanswered by the police department — his rear radar clocked a sedan going 70 mph in a 35-mph zone. Crews sped up to overtake the sedan, getting up to 77 mph. Crews later said that, in accordance with a department policy allowing officers to engage in a "silent response" to prevent a traffic stop from turning into a high-speed pursuit, he didn't turn on his siren or emergency lights to pull over the speeding sedan.

“A car came over the hill, flashed its lights at either me or the moped… I assumed they were doing that either to say, ‘Hey, you don’t have a headlight’ or something else, I wasn’t sure,” Riley says in his deposition. “The moped slowed down abruptly. I thought I was going to hit it, which caused me to slam my brakes on.”

Crews later said he didn’t see Harden’s scooter until it was less than five feet in front of him. He slammed on his brakes, but it was too late. He crashed into the scooter, which was turning into a driveway. Harden had been going no more than 27 mph when the scooter was hit by Crews, who was going 70 mph. Harden and Thomas were thrown approximately 60 yards. The scooter was trapped under the police car, which kept going for another 90 yards after the collision. “All I can remember is that [Crews] said, ‘I didn’t see them,’” Riley recalls in his deposition. “He was pretty shaken up.”

Harden’s autopsy says he died of multiple blunt force injuries, including a traumatic aortic rupture and a skull fracture. His body was destroyed. According to autopsy reports, both men had been drinking; Harden had a blood alcohol content of .16, twice the legal limit, and Thomas had a blood alcohol content of .19. Harden also had marijuana in his system.

Police claimed that Harden stole the scooter he was riding. Harden’s family disputes this. According to the aforementioned reconstruction report, the scooter was registered to a Raleigh man who reported it stolen on May 19, a few weeks before the incident. A handwritten receipt provided to The Outline says that a man by a different name, Robert Jackson, sold it to Harden on May 13.

At the conclusion of the report, Raleigh police seemingly absolved Crews of all wrongdoing. “It is unknown if the crash would have occurred if Officer J.H. Crews was traveling at a lesser speed,” the report says. “A reduction in speed would certainly have reduced the likelihood of fatal injuries to Mr. Harden and Mr. Thomas. It would have also afforded Officer Crews a longer reaction time and distance, during which he may have been able avoid [sic] the scooter that was traveling in his lane.”

“An examination of all of the evidence,” the report says, citing Harden’s alcohol levels, his speed, the lighting on the scooter, and “his maneuver into the wrong lane of travel in order to enter a driveway he is unfamiliar with” – i.e., turning – “were the proximate cause of death of Maurice Antonio Harden and Trindell Devon Thomas.”

In 2015, Flood brought a civil suit against Crews and the city of Raleigh for wanton negligence, punitive damages, and negligent supervision and training on the part of the city, to which the city countered that Harden’s drinking and faulty equipment on the scooter counted as “gross contributory negligence.”

“The loss of life that occurred on June 5, 2013 is a terrible consequence that sometimes follows a lawful police apprehension or pursuit,” Raleigh city attorney Thomas McCormick wrote in a brief on behalf of Crews and the city, calling for a full dismissal. “That sad loss is the fault of the lawbreaker who was speeding along Skycrest Drive at 70 mph in a 35 mph zone.” The sedan Crews was chasing was never found.

Late last summer, as depositions for the lawsuit were ongoing, Aisha Flood was describing the process to Terry. He burst into tears. “Why do we have to go through this? Why couldn’t it be somebody else?” he asked her.

“I remember him saying, ‘You see this on the news and you hear about it, but you never think it’s going to be your family,’” Flood says. “And then he just walked out of the room.”

In January, a Wake County judge dismissed the Harden case, writing that there were “no genuine issues of material fact.” The family is currently reviewing its legal options.

Jaqwan Terry was born in September, 1991, 13 months before Maurice. Growing up, however, Harden was the one who usually took charge. “Maurice was the daredevil, he was the one that would go try stuff,” Flood says. “Jaqwan was the type to stand back and wait for Maurice to do it, and then he’d go do it too.”

Their family says the two brothers were inseparable as kids, and continued to be close when they got older. At one point, they even dated two sisters “to make it convenient for them,” Flood laughs.

Whereas Harden was outgoing, Terry was introverted, a “pretty boy,” and more emotional — even when his sisters would order him to do something as innocuous as brush his teeth. “He’d get defensive about everything,” Flood says.

“Have you ever met the type of person where what they show you is exactly who they are?” asks Seneca Clark, Terry’s former girlfriend and the mother of his young daughter. “A lot of people depended on him, he was a provider. If anyone called him for anything he was right there.” Flood says that after he died, she found out that Terry often bought food for people in Heritage Park, an affordable housing community where many elderly and handicapped people live, and once bought sneakers for a woman’s son when she couldn’t afford them.

Terry, whose son from a previous relationship was born a few months after Harden’s death, met Clark in early 2014; by March of that year, they were a couple. They stayed together when he went to jail for six months after a DWI conviction. “When he was in jail, he said to me, ‘When I get out, I’m going to get you a place, and we’re going to have a baby,” she says. Their daughter was born in January 2016.

Clark says Terry worked several jobs to take care of his family: at a temp agency, for a garbage collection company, and as a janitor, sometimes working from early in the morning until into the next one. Terry often thought about how his two kids would never get to meet Maurice. “[Harden] was his best friend,” Clark says. “After I got pregnant, he would always say, ‘I wish my brother was here to see my daughter.’”

But Terry would rarely open up about the deep sadness that came with Maurice’s death. He would often tell Seneca that he was “ready to go see my brother.” Clark says she repeatedly told him to get help. “When Maurice died, a lot of Jaqwan died as well,” says Ashley McCleod, Patricia Harden’s birth daughter who considers her cousins her siblings. “And the stuff that he did out of character wasn’t his character.”

When Terry was level-headed, he was a loving father and boyfriend; other times, he would get so frustrated that he would hit himself in the head, or threaten Clark in what she calls “outbursts.”

Before his brother’s death, Terry had a few non-violent charges; mostly drug, DWI, and concealed carry-related. But in the month after Maurice died, he picked up two DWIs in three days. A year later, in September 2014, Terry was charged with assault in Myrtle Beach, S.C., after witnesses saw him “grab a woman, choke her and punch her in the face.” And in the year leading up to his own death, Terry had several run-ins with police, including another gun charge and three drug possession charges.

Before he died, Terry talked about enrolling in barber school. He also talked about moving to Texas. Later, a neighbor would tell the News and Observer that Terry was a “pretty good guy,” but that it “seemed like he had a lot on his mind.”

Early in the morning of July 21, 2016, a 911 call was placed about an argument at Seneca Clark’s house. "I was downstairs about to fall asleep,” an unidentified woman says. “He comes downstairs kicking and screaming. He starts barging at her with the baby. So, I take the baby, and he runs after me screaming, and he comes back in the house to get a knife, and he chases me up the road.” In a separate 911 call, a neighbor said that Terry had a gun.

According to court records, Terry pushed Crystal Clark, Seneca’s mom, into a wall, and held a knife to Seneca’s throat. He was charged with assault on a female and assault with a deadly weapon, and the Clarks obtained a restraining order.

On the night of August 28, Seneca Clark says she told Terry over the phone that she wanted to end their relationship. The next morning, in another phone call, they got into an argument. He told her she wasn’t going to leave him, and that he was coming over with a gun. “I didn’t know what he was going to do, and my daughter was in the house, so I just called the police,” she says.

Clark called 911 at 11:36 a.m. Raleigh police officer B.F. Burleson arrived at the house a short time later and spoke with her. In the middle of their conversation, Terry reappeared outside the house. Clark pointed him out to Burleson, who called out Terry’s name. Terry began walking away, hit a corner, and ran.

What happened next remains contested. According to the preliminary report released afterwards, Burleson chased Terry to a fence a block away, where he dragged him down and attempted to handcuff him. During the ensuing struggle, “Officer Burleson observed a handgun on the ground directly underneath Mr. Terry,” and tried to push him away from it. He failed; Terry picked it up. Terry fired and hit Burleson in the right leg and at “approximately the same time,” Burleson returned fire. At some point, another officer, B.S. Beausoleil, showed up and also fired at Terry. The entire exchange lasted about five seconds.

Terry’s autopsy found that he was shot eight times: in the neck, arms and legs, and abdomen. It also said that he was bipolar and paranoid schizophrenic. Flood disputes those diagnoses, but said her brother never went to the doctor. (In response to questions about how the medical examiner came to that conclusion, a North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson said that information is “gathered from a variety of sources, including law enforcement investigation, medical history, witnesses at the scene and/or the decedent’s next-of-kin.”)

Three years, two months, twenty-four days, and roughly nine hours after his brother’s death, Terry was pronounced dead at approximately 12:19 p.m on August 29, 2016.

The State Bureau of Investigation’s probe into Terry’s death took more than six months, but in April, District Attorney Lorrin Freeman announced that she wasn’t pressing charges. “Based on all the evidence available,” her report says, “it is the conclusion of the District Attorney that Officers Burleson and Beausoleil shot Mr. Terry in self-defense and as a matter of last resort and only because they reasonably believed Officer Burleson’s life was in danger.” (Requests to interview Beausoleil and Burleson went unanswered.)

Freeman’s decision, according to the report, was based on the statements of the officers, a witness who didn’t see the shooting but heard the commotion, and physical and forensic evidence. The state crime lab confirmed that there was gunshot residue on Terry’s hands, but that they weren’t able to find fingerprints or build a DNA profile “from the magazine base and the projectiles.”

Aisha Flood is frustrated that the case has been closed without that information. “The police took both my brothers and people ask me how am I feeling,” she texted me the day after the meeting. “If you only knew what was going through my mind. My heart is so heavy… I don’t have peace.”

Over the past year or so, a coalition of local activists known as the Raleigh Police Accountability Community Taskforce (PACT) have pushed for reforms to create more citizen oversight of the police force and worked to increase visibility on cases like Terry’s and Harden’s. These proposals include an expansion of the city’s crisis intervention program, the creation of a community oversight board with subpoena power akin to Atlanta’s — that city’s board can investigate citizen complaints against police and corrections officers, and make disciplinary recommendations – and the “deprioritization” of enforcing marijuana law. According to PACT numbers, African-Americans account for 67 percent of low-level marijuana arrests in Wake County despite making up just 21 percent of the population.

But activists haven’t seen many of their proposals implemented. The city told PACT in May 2016 that the state legislature would need to give them the authority to create a community oversight board with subpoena power; in response, PACT asked for a recommendation from the city. The city has so far declined to provide one. City officials also denied requests to de-prioritize marijuana enforcement, and said that existing policies regarding officer recruitment diversity and crisis intervention trainings were good enough.

According to a letter sent by the ACLU of North Carolina and PACT to Raleigh mayor Nancy McFarlane — there were an average of 34 citizen complaints per year, in a city of 439,000 people, from 2011 to 2015. Only 31 percent of those complaints were sustained, which means, based on literature from the Raleigh P.D., that “facts exist which prove specific allegations or other wrongdoing discovered during the investigation.”

Akiba Byrd, a community activist in Raleigh, says that making complaints against police officers can carry a chilling effect; Flood, for example, said at a city council meeting in March of this year that she and her family had been stopped 23 times by the police since bringing the lawsuit against the city.

“Nobody uses the system because they get targeted,” Byrd says. “You go into the station to get the papers, you might deal with the officer. It’s ridiculous. So that’s why it’s important for us to have our own opportunities to do this.”

Maurice and Jaqwan’s families are trying to move forward. Aisha Flood went to college for criminal justice and, at one point, worked for the county’s register of deeds. The loss of her brothers, though, caused her faith in the system to evaporate. “I miss the job that I did,” she says. “But I don’t think I would ever go back to it…I don’t see where [the justice system] is helping us anymore.”

McCleod wants to become a lawyer, but withdrew from law school when Harden died. She was planning to try again when Terry was killed.

“When Maurice died, I lost hope, I lost myself, I lost my dream, I lost my drive,” she says. “But it’s a bigger picture than us now. And I feel like I have to be an advocate for the disadvantaged, and I just have to fight more… It’s just not right, and someone has to make it right.”

Seneca Clark says her family has been rendered homeless following Terry’s death. When we met, they were living at a motel in the Raleigh suburbs.

“I have to replan my whole life,” Clark says, holding back tears. Despite everything, she and Terry had planned to get married. “Sometimes I have good or bad days, but my life has completely taken a turn. Nothing is the same. I didn’t think I was going to have to raise my daughter by myself. We lost our home, we lost everything. I have nothing. So it’s hard.”

In early March, Aisha Flood stood with Ashley McCleod and Rolanda Byrd – Akiel Denkins’ mother, with whom she’s formed a friendship – before the Raleigh city council to ask for an apology for Harden's death. Wearing a shirt with a picture of her brothers on it, she described the sense of safety that her family had lost. “I’m scared some days to leave [my house] because of depression and not knowing what to expect,” Flood said. “My [youngest] sister lives in fear every day, and when she leaves the house, I’ll never know if she’s going to come back… my mother’s whole mental state has changed. She went from weighing 200 pounds to 110 pounds. Now, she’s not even the same mother. She’s lost everything because of Raleigh P.D.”

“When the justice system has failed us as a whole, who do we look at?” she asked. “We have nobody.”